Every year the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change convenes its conference to discuss procedures and protocols for offsetting carbon emissions and establishing a loss and damage fund for vulnerable nations going forward.

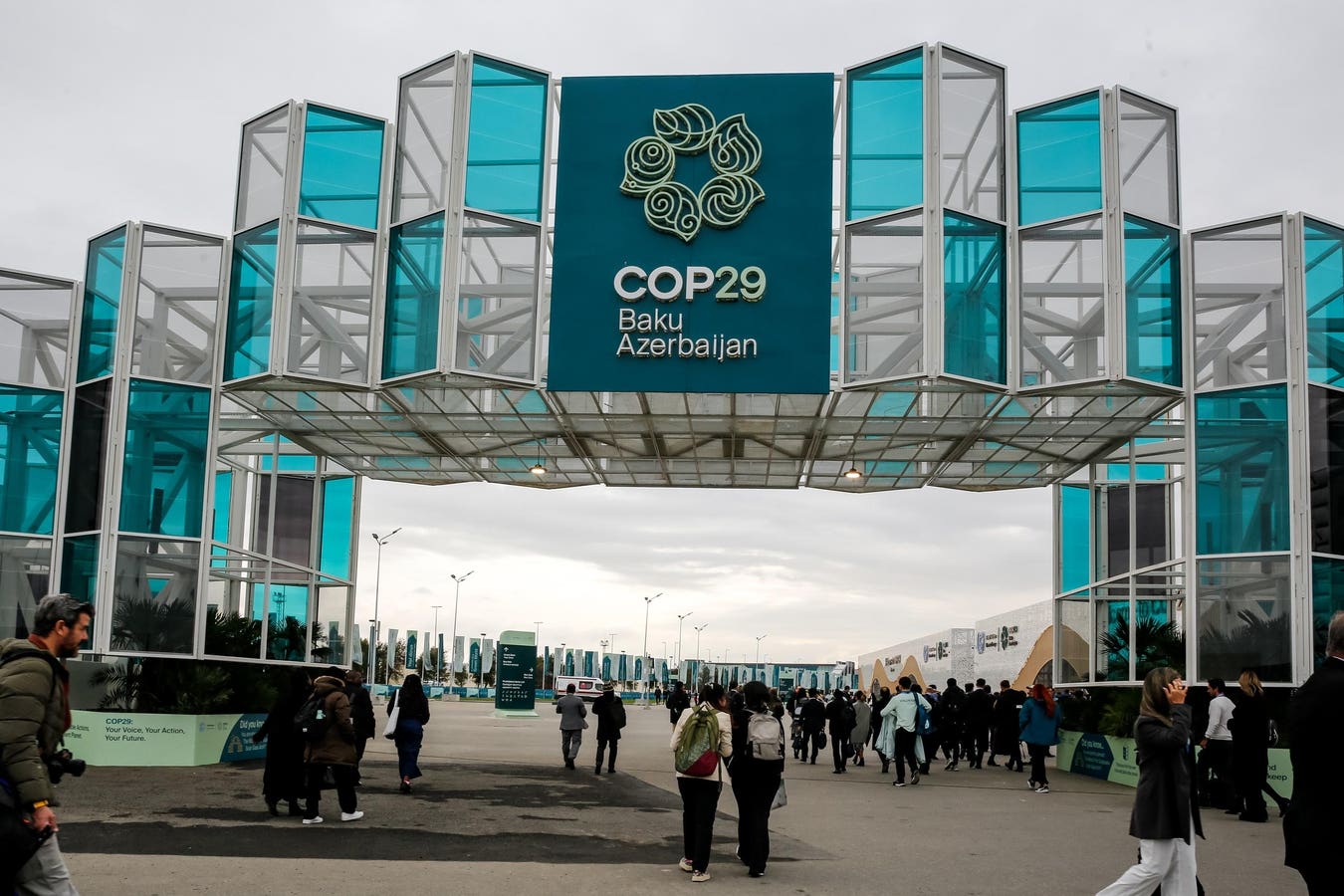

Dubbed the Conference of Parties or “COP”, UNFCCC’s latest outing – COP29 scheduled to conclude after 11 days of deliberations on Friday in Baku, Azerbaijan – was meant to be an ambitious ‘climate finance’ COP. It turned to be anything but.

That’s because a combination of international political shenanigans, unrealistically lofty ambitions on financing, and economies digging their heels on fossil fuels came to the fore creating an atmosphere that ultimately proved very hard to recover from.

A Cheap And Abundant ‘Gift Of God’

For starters, if a nudge away from fossil fuels was the general idea, the hosts certainly did not get the memo. In his opening remarks convening COP29, Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev described oil as a “gift of god” doubtless conscious of his country’s plentiful reserves he has no intentions of abandoning.

His quip was later backed up by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ secretary general Haitham Al Ghais who noted: “Oil and gas are indeed a gift of god. They impact how we produce and package and transport food and how we undertake medical research, manufacture and distribute medical supplies. I could go on forever.”

It also just so happens that oil prices are currently at lows last seen in 2021 and may go lower in the face of lackluster demand in China and rising production.

The natural gas lobby did not wish to be left behind either, with Mohamed Hamel, secretary general of the Gas Exporting Countries Forum, telling COP29: “As the world’s population grows, the economy expands, and human living conditions improve, the world will need more natural gas, not less.”

He also said a deal on international climate finance should allow support for more natural gas projects to help countries transition away from dirtier fuels like coal.

With a perceptively pro-fossil fuel stance of many in Baku, discord spilled out into the open. It is something which previous oil and gas producing COP venues like Egypt, UAE and Scotland had managed to largely avoid.

A lack of presence by leaders from the world’s major economies made a bad situation worse behind the many green pavilions, facades and exhibitions exalting clean technologies and collaboration on lowering global carbon emissions.

Anyone There?

The conference, already reeling from the prospect of a pro-oil U.S. presidency of Donald Trump following his recent election victory, was given a miss by the current president Joe Biden.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, India’s prime Minister Narendra Modi, China’s president Xi Jinping, Russia’s president Vladimir Putin, Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau, South Africa’s president Cyril Ramaphosa and Australia’s prime minister Anthony Albanese did not attend either.

Germany’s chancellor Olaf Scholz cancelled a visit after the breakdown of his ruling coalition a week before COP29. Brazil’s president Lula da Silva – who will be the host of COP30 next year – could not travel either due to a head injury he sustained last month.

The U.K.’s relatively new prime minister Kier Starmer did briefly attend with a huge 470-strong delegation in tow, drawing widespread ridicule at home on his carbon footprint and expense for the trip, having instituted cuts and tax rises since taking office in July.

Meanwhile, France withdrew its top envoys after criticism from Aliyev who described the country as a “colonial” oppressor. President Emmanuel Macron had already made a decision not to attend in advance of the conference. Argentina, home to one of the world’s largest shale reserves, also pulled its envoys out merely three days in to the conference.

Another 100 world leaders did attend. But the shrinkage of the conference was visible with less than half the number of delegates compared to COP28 in Dubai last year which logged an attendance of over 83,000 delegates.

Not Quite $1.3 Trillion

Among those missing were large numbers of venture capital funds, private equity firms, major investment bankers and financiers – all of whom were very visible in Dubai raising hopes for a true ‘climate finance’ COP 12 months on.

The idea was to achieve a new collective quantified goal – a colossal funding pool provided by developed countries to finance the climate mitigation efforts of developing countries. Figures being brandished about by UN agencies were in an eye watering range of $1.1 trillion to $1.8 trillion a year, and finally pinned to $1.3 trillion at the latter stages of COP29.

Instead, not even a fifth of that was pledged on Friday, when a figure $250 billion a year by 2030 was outlined on the conference’s final official day to howls of disappointment.

NGOs and environmental organizations ranging from the Alliance of Small Island States to Greenpeace lined up to criticize the figure, while politicians from developed nations defended it noting they were not in the business of signing blank checks.

However, even what is being offered is an improvement based on past form. The last pledge was to deliver at least $100 billion a year from 2020 onward. That goal was only reached in 2022, some two years too late. It is why demanding north of a trillion dollars a year in a fraught global political climate is the stuff of fantasy.