Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Geoff Bennett: Civil rights attorney Maya Wiley grew up in a household that prioritized activism. Her parents’ influence set her on a path to a lifetime of advocacy work, and yet sometimes left her wondering how best to fulfill the family legacy on her own terms.

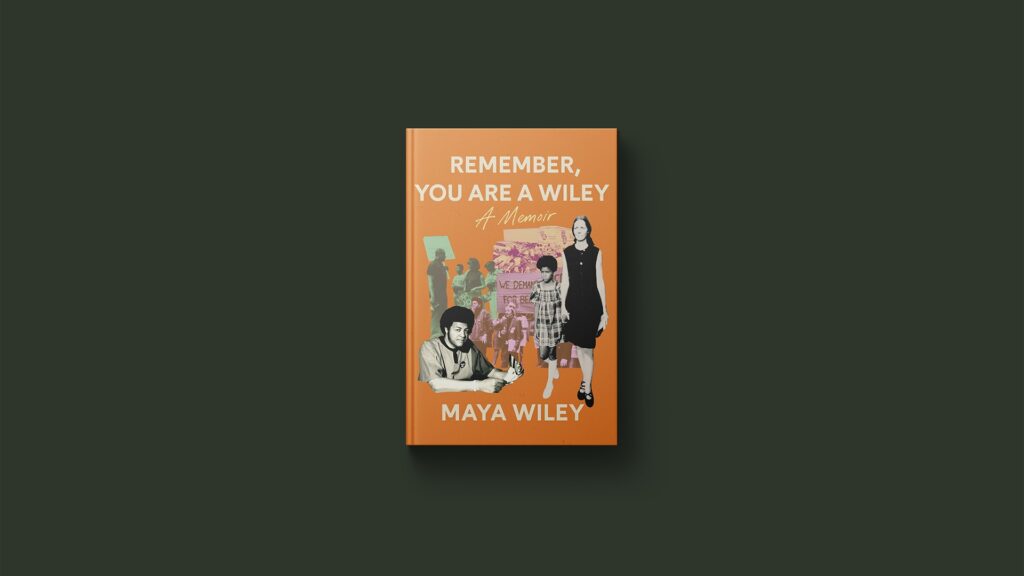

Her memoir, published this week, is called “Remember, You Are a Wiley.”

We recently sat down to talk about it.

Maya Wiley, welcome to the “News Hour.”

Maya Wiley, Author, “Remember, You Are a Wiley”: Thanks so much for having me, Geoff.

Geoff Bennett: So much of this book is an untangling of your parents’ influence. Your father was a prominent civil rights leader and social activist, George Wiley. Your mother, Wretha Wiley, was an academic and a civil rights activist in her own right.

How did their activism shape your life and shape your values?

Maya Wiley: You know, they shaped me so profoundly that it felt so important to write this book.

And what I mean by that is that, when you’re growing up with parents — my father died when I was young, when I was 9 years old — you know that they’re impacting you, but they also spend a lot of time making sure we could be who we wanted to be and not insisting that we be who they were.

And I realized that what they really did was modeled what it meant to rise to the occasion of a time you’re in, to recognize that to those who have been given much, much is expected. That was a clear kind of value principle in my household growing up, and that the expectation is you would do it. You would step up in any way you could.

And, for me, watching their activism, I remember it was both at times painful because I wanted or needed them, but also it made me incredibly proud.

Geoff Bennett: And theirs was an interracial marriage, and you write about your parents. There was no cultural difference between them. They were both raised in similar strict Christian traditions. Your father’s darker skin was an incidental problem, you write, for your mother, not a fundamental one.

How did your parents break free from the bonds of cultural expectation and racism, frankly, in the early 1960s and build a life together?

Maya Wiley: Well, that was such a powerful part of what shaped me, because they were both in their separate ways growing up differently, my father in the North, my mother in West Texas, in a pretty racist Southern Baptist town.

I mean, they found their own paths to their voice and to their identities in a racist society on very different paths, but they ended up in the same place. And I think it’s that fact, what shaped them that made them so comfortable with who they were, despite how much the world was trying to make the penalties too high for them to be who they were.

It was an important life lesson to me. And I realized how much of it had to do with just a refusal to go with the flow if the flow was wrong, if it was unjust. They really, really, really challenged any injustice that they found, whether it was in their personal lives or in the lives of others. And that was a very high bar that they set for me.

Geoff Bennett: I imagine that was particularly important for you because you write about how you were this mixed-race kid growing up in a Black neighborhood in D.C. who was sometimes bullied for having a white mother.

And yet, years later, you were the only Black lawyer out of 50 at the U.S. attorney’s office when you worked there as a young woman.

Maya Wiley: When I went to the U.S. attorney’s office, I already knew that we had not yet arrived at that mountaintop that Martin Luther King talked about.

But I was certainly challenged in a way I hadn’t been before because I was so fortunate to grow up in a way where I hadn’t experienced anyone actually questioning my qualification. I was — well, some in college, for sure, and, in law school, sure. But, professionally, that was a new low.

But, again, my parents had been through so much worse, had taken on and been challenged by so much worse. And I just remember thinking, well, as long as I can stay true to who I am and show them, show them what I’m made of and show them that I’m going to be a lawyer, that when I leave that office, they’re going to be sad to see me go, and that — part of that was remembering I am a Wiley.

Geoff Bennett: A question about activism, which is such an ever-present theme in this book. Activism comes, as you know, in so many forms, public protest, legal and political advocacy, community organizing.

You ran to be the mayor of New York City back in 2021. So I have the question, which approach do you think is more effective, trying to effect change from the inside, from the seat of power, or from trying to effect change from the outside?

Maya Wiley: I love that question, Geoff. And I’m so grateful you asked.

Having been able to be on all sides of those senses, I will tell you this. It is every single one of them. There is simply not one thing that must happen. You need the activism, you need the direct action of protest, of people who put their feet in the street to peacefully demand change, and have those demands be heard.

But you also have to have people who are helping to vindicate the wrongs in court. You have to have the judges who understand what needs to be vindicated. And you need the elected leaders that understand the power of the pen, who will listen to those in communities, those who are protesting and say, let’s figure out the actual solutions to the problems you’re raising.

Geoff Bennett: The book’s title comes from a family mantra of yours. It was your father’s mother who would say, “Remember, you’re a Wiley.”

What has that meant to you over the course of your life?

Maya Wiley: You know, it’s been a challenge. It meant a challenge to understand and what it means to be a Wiley, that sense of both pride but also that sense of responsibility.

Part of what she meant is, you — those Black kids are going to be out in these white streets. You need to show them who we are. You need to be responsible to what that means, and trying to figure that out also as my parents kind of created their own definition of what it meant to be a Wiley that I needed to live up to.

I’m very proud to be George and Wretha Wiley’s daughter. And every day, I wonder, am I rising to the challenge they laid before me by not telling me what to do, but by showing me through their own example what it really means to be a Wiley?

And so it’s something I have struggled with my whole life, but it’s been worth every ounce of that struggle.

Geoff Bennett: The new memoir, “Remember, You Are a Wiley.”

Maya Wiley, thanks so much for being with us. Always a pleasure to speak with you.

Maya Wiley: Thank you, Geoff. The pleasure is mine.

Support Canvas

Sustain our coverage of culture, arts and literature.