What is the 50-50 profit-sharing formula?

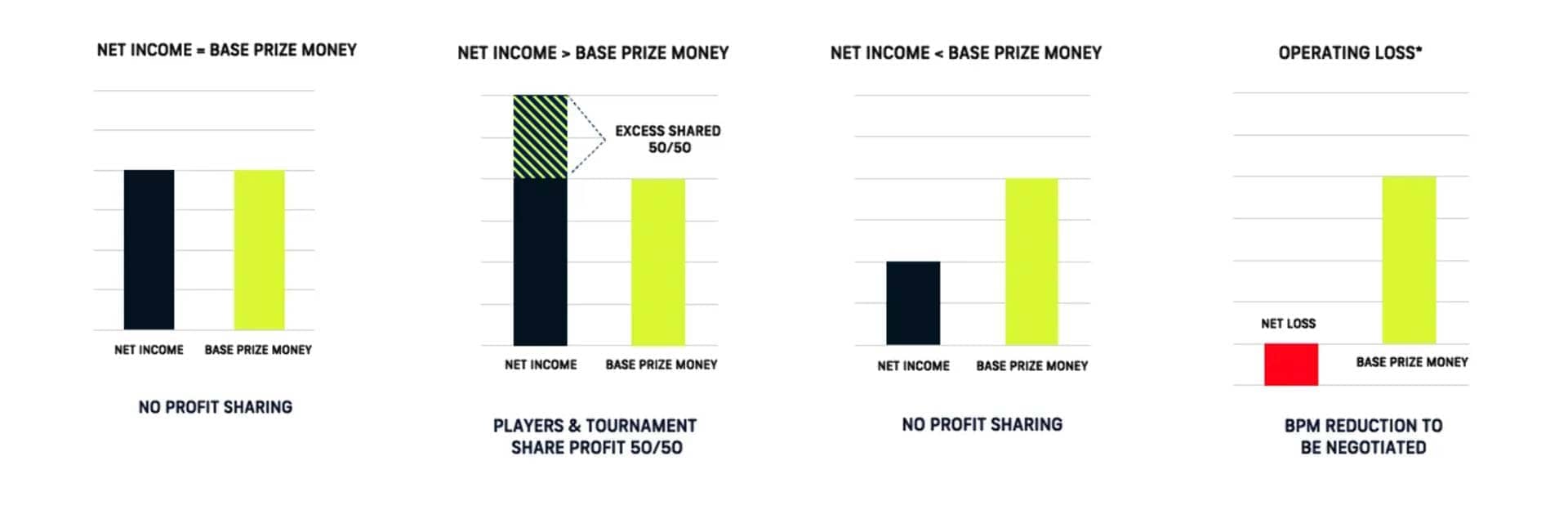

The formula was introduced as one of the central pillars of the OneVision strategic plan. In simple terms, the formula means that any net profits (before income tax) above Base Prize Money across the ATP Masters 1000 category are split 50-50 with players. This means that players are sharing in the financial upside of tournaments for the first time in the history of the ATP Tour.

How does it work?

It’s a three-step process:

1. Tournaments take place, with guaranteed Base Prize Money paid out to players as usual.

2. Following each tournament, its financials (incl. all revenues, costs) are fully audited. This is done for each of the nine ATP Masters 1000 tournaments.

3. Profits are aggregated across the whole category (nine ATP Masters 1000 tournaments). If the profits exceed the value of the total Base Prize Money paid out across the category that year, the excess is shared 50-50 with the players via a Bonus Pool payment.

How much profit sharing has been calculated for the 2022 season?

The formula will deliver an additional $12.2m to players for the 2022 season. For context, this represents an additional 22.8% on top of Base Prize Money at the eight Masters 1000 events that took place in 2022 ($53,592,365). Shanghai did not take place in 2022 due to Covid-19 restrictions.

Why has it taken so long to confirm Profit Sharing for the 2022 season?

Tournament financial auditing is thorough and complex. This process takes time – particularly in its first year. There are in fact three different audits that take place:

1. Tournament Independent Auditor (various), which must pre-approved by ATP

2. Prize Money Committee Auditor (PWC)

3. Player Auditor (KPMG)

In addition, tournaments must wait for the end of their respective fiscal years for the auditing process to begin. However, we anticipate that calculations will be completed more quickly in the future as stakeholders become accustomed to the process.

How is the Player Auditor selected?

The Player Auditor is selected by player representatives on the ATP Board. It is important to stress that the Player Auditor (KPMG) has vast experience handling all auditing and accounting matters. The Player Auditor represents the player interests and ensures accuracy and fairness from a player standpoint across these items.

Why is tournament auditing such a big deal for players?

In any successful partnership, financial transparency is fundamental. The ATP, a partnership between players and tournaments, is no different. The process gives the player auditor full visibility on the economics of tournaments for the first time ever, building trust and transparency. It also gives players a clearer understanding of the costs involved with running a tennis tournament. The cost of additional requests — for example accommodation, food, transportation, or upgraded facilities — can be seen in the P&L and ultimately impacts profit sharing to players.

How is the profit-sharing formula distributed?

The total amount is distributed centrally by the ATP to the singles players that competed across the Masters 1000 category, based off their performance. The more Pepperstone ATP Ranking points a player has won at those events, the greater amount of profit sharing he will receive.

The total value of the profit-sharing distribution ($12.2m in 2022) is divided by the total ranking points at stake across the category (40,758 in 2022), to establish a value per point – in this case, $300. For illustrative purposes, a player who won 10 points in 2022 across the ATP Masters 1000s, would receive $3000. Points won in the qualifying rounds are included.

For the 2022 season, the profit-sharing formula will deliver a distribution to 150 players.

Which revenues are included in the formula? Why is it not just a straight revenue share?

The ATP profit-sharing formula includes all revenues – from ticketing, event day, media (broadcast and streaming) & sponsorship – except for data revenues. The reason data revenues are excluded is they are considered an ATP asset, not a tournament asset. They are managed centrally by Tennis Data Innovations (TDI) and distributed directly to players at the source (and in equal measure to tournaments). As such, data revenues are excluded from the formula, otherwise the players would capture the benefit of data twice. For clarity, the fact that data revenues are not accounted in the profit and loss of the tournaments is more advantageous for the players.

Regarding a revenue share, it’s important to note the following:

1. Other sports that operate on a revenue share basis frequently carve out certain revenue streams from their agreements, meaning that the players’ share is significantly lower than 50%. ATP’s profit-sharing formula includes all revenues, except data revenue paid to players directly from the source.

2. The structure of many team sports gives the leagues and teams more centralised authority over athletes, as employees. This can mean restrictions for athletes on personal endorsements/sponsorships, usage of name/image/likeness, as well as control over when and where athletes can compete and how they manage their schedules. As independent contractors, tennis players retain more control over their personal brands, with much greater freedom to plan their playing schedules, including exhibition events.

3. The economics of tennis are unique. Relative to other sports, our infrastructure and operational costs are higher relative to revenues, which results in lower profit margins. Stadium and facility costs and maintenance expenses are high and yet promoters are only able to maximise their return during their tournament week(s). This contrasts with most major team sports, where teams use the same venues throughout the season, enabling them to repeatedly generate greater returns relative to their infrastructure costs.

4. Media revenues constitute a relatively low share of our sport’s overall revenues compared to other sports, partly due to our fragmentation (something we are addressing with OneVision). Tennis relies heavily on ticketing, which is a cost-heavy revenue stream with relatively limited scalability.

These factors combine to mean that that a 50-50 revenue share would simply turn our tournaments into loss-making entities, which would not be sustainable for the sport. The partnership would simply not work under such terms.

With this in mind, a profit-sharing formula was chosen in order to deliver:

- alignment of the interests of tournament and players

- complete transparency

- long-term sustainability

It is also important to note that the tournaments assume the risk of their enterprise in full – with players guaranteed 100% of prize money even if the event makes a loss. While a career as a professional tennis player presents its own financial risks and uncertainties, players do not share in the financial risk of events (but do share in the upside).

Is the profit-sharing formula linked to the expansion of the Masters 1000 events to 12-day events?

Yes. Our OneVision strategy puts forward a package of reforms that aim to elevate the sport as a whole. No single benefit should be viewed in isolation.

It is important to state that the reforms ushered in under OneVision have generated an additional $50 million of income to players, through increases in Base Prize Money, Bonus Pools, and Profit Sharing, in 2023 alone. And if you factor in record-breaking player pension contributions, the number goes up even further.

The payment of these increases, plus the new tournament financial transparency requirements, are terms that tournaments have agreed to as a direct result of the event expansion and longer category terms offered under OneVision. This has also meant bigger draw sizes and more playing opportunities for players further down the Pepperstone ATP Rankings.

While the profit-sharing formula has delivered immediate returns for players in its first year, we must also keep in mind the value of the foundation it creates. No matter how high or low the distribution is each year, the success of the formula is that it provides a fair and accurate measure of the financial state of the Tour, and how our members share in the upside of our business. Above all, the formula is about enhancing the equal partnership between players and tournaments on the ATP Tour, aligning interests and generating trust across both sides of the membership.

If a tournament owner sells its tournament class membership, the ATP typically receives a transfer fee. Subject to its financial performance at the close of the fiscal year, ATP’s 50-50 partnership structure enables it to rebate membership dues/fees and increase contributions to the player pension. Transfer fees can contribute to these payments, meaning players indirectly benefit from the value of a tournament and a tournament transfer.

Why are capital expenditures, for example costs related to renovating or building stadia, included in the formula? And what happens if a tournament is sold?

Capital expenditures are included in the profit calculation. This is common in business and not unique to our sport. The required basis of accounting for each tournament’s income statement is generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in the respective country. While there may be differences in GAAP in different regions around the world, all provide for recognising capital expenditures in the income statement through depreciation of those expenditures over the expected life of the asset purchased. For profit calculation purposes, depreciation is only related to the respective tennis event. In other words, if a facility or other assets are used for other purposes (for example if a facility hosts other events during the year), then an allocation between events/uses will be required. Importantly this ensures that revenues generated by tennis are not being unfairly used to fund capex elsewhere.

Equally, profits from the sale of infrastructure previously depreciated are also captured in the formula and allocated according to similar principles.

Finally, if a tournament sanction is sold or acquired, this is not captured in the formula. However, the ATP typically receives a transfer fee. Subject to its financial performance at the close of the fiscal year, ATP’s 50-50 partnership structure enables it to rebate membership dues/fees and increase contributions to the player pension. Transfer fees can contribute to these payments, meaning players indirectly benefit from the value of a tournament and a tournament transfer.

Given that some of the ATP Masters 1000 tournaments are combined, how do you factor in the costs & revenues that are split between ATP and WTA?

Revenues that can be directly attributed to ATP – for example broadcast, streaming and central sponsorship – are allocated directly and in full to the profit-sharing formula.

Revenues that cannot be attributed directly to either ATP or WTA – such as ticketing, event day, and local sponsorship – are allocated 50-50 between ATP and WTA. Costs are also split 50-50. So, in the case of capital expenditure of a combined ATP/WTA Masters 1000, only 50% of these costs would be factored into the ATP formula.

Why is the formula calculated as an aggregate across the whole category and not on an event-by-event basis?

We believe this is the fairest way for the formula to operate, minimising the impact of any outliers (high profits or high losses) from the equation, and assessing the performance of the category as a whole. We believe that taking an aggregate provides a fair and accurate picture of the state of the business, a position that can ultimately also protect the players.

When will we see the profit-sharing formula applied to other tournaments beyond the ATP Masters 1000?

ATP 500 events have adopted the same financial auditing requirements in 2023, in anticipation that the formula will kick in as the events’ financial performance allows. In the long run, we aim for all categories on the ATP Tour to adopt the same formula, including the ATP 250s.

How is prize money at the Grand Slams determined?

Unlike ATP tournaments, Grand Slams are independent entities that ultimately determine their own prize money levels. Grand Slams do not sit within the ATP governance structure.

Our focus has now firmly turned towards Phase 2 of OneVision, which focuses on greater collaboration across the T-7. This is where the real opportunity lies to deliver incremental value for everyone.