Before I immersed myself in the world of Mt. Everest’s climbers by writing a novel about them, Dixon, Descending, I was full of more judgment than understanding. When I asked friends their thoughts on what could compel someone to climb the world’s highest peak, we often came to the same conclusion: ego. It was a holier-than-thou kind of judgment, one too often echoed on blogs—“Who does this?”—or in newspapers—“Are mountain climbers selfish?” (New York Times, Opinion, April 27, 2019).

Perhaps we dismiss mountaineering’s dangers the way I always dismiss the danger of being eaten by a shark: I don’t swim. I particularly don’t swim in the ocean. That’s how I avoid being eaten by a shark. That’s how I avoid taking seriously the idea of being eaten by a shark. But I’ll never know what it is to rise on a wave, knowing my own graceful strokes can return me safely to shore. I’ll always be a bystander. Once, I stood at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean with a guy who said that when he looked out at the dark sea at night all he saw was death. I knew it would be our last date. Because the ocean’s unknowable vastness filled me with such awe.

I’ve come to feel that way about mountains. Rather, I’ve come to open myself to the enigma of mountain climbing. The idea terrified me, I’ll admit, and I found myself initially viewing the subject the way my long-ago date did: as a tale of the dying. In fact, mountain climbers face the thin veil between life and death. But how many of us live so fully as to skirt that edge? Mountain climbers do it willingly. Not because they want to die, I’ve been told, but because they are alive.

Through books and movies, we gain a close-up view of mountaineering in all its elation and harrowing detail without actually risking death. The best of these books delve into the “why” questions to give us more nuanced accounts of the triumphs and tragedies that so often go hand in hand in the mountains and in the lives of climbers.

Mountains of the Mind: The History of a Fascination by Robert MacFarlane

Mountains of the Mind: The History of a Fascination dives right into the “why” of climbing. Macfarlane excavates society’s attraction to mountains while telling both the historical story of the mountains’ pull and his own personal story of climbing. How, he posits, can the “the beauty and strangeness” of mountains supercede their dangers?

Four Against Everest by Woodrow Wilson Sayre

Woodrow Wilson Sayre, the grandson of President Woodrow Wilson, wrote of his near-fatal 1962 journey on Mt. Everest in Four Against Everest. Sayre said afterwards that he made the trip to show that mountain climbing could be achieved without high-priced expeditions and that success depends only on one’s own abilities, not on social standing or family reputation. Readers will decide whether his journey—during which he faced hunger, abandonment by porters, and a fall into a crevasse—proves his point.

The Mammoth Book of Eyewitness Everest edited by Jon E. Lewis

The Mammoth Book of Eyewitness Everest offers a compelling compendium of climbers’ detailed and often intimate stories, starting with a 1913 account of the first notions that Everest could be climbed, through the 1996 discovery of the remains of George Mallory, who had been lost in the first recognized summit attempt in 1924. Along the way, climbers from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s relate their experiences on the mountain.

Fragile Edge: A Personal Portrait of Loss on Everest by Maria Coffey

In Fragile Edge: A Personal Portrait of Loss on Everest, Maria Coffey shares her perspective as the partner of mountaineer Joe Tasker. From her, we learn what it’s like to be left behind each time a partner leaves on a journey from which he may not return. Even when he does return, he is often changed by the mountain, left brooding and restless. When Joe’s dream of climbing Everest turns deadly, Maria must seek the path forward from regret and grief.

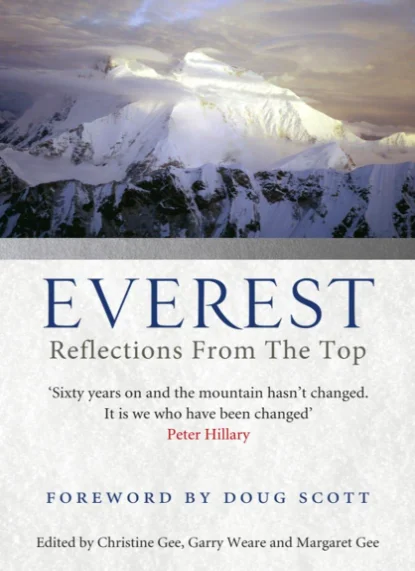

Everest: Reflections from the Top edited by Christine Gee, Garry Weare, and Margaret Gee

Everest: Reflections from the Top, a compilation of stories created to mark the 50th anniversary of Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s successful first summit of Everest, offers short but highly personal accounts by climbers. They note their motivations, triumphs, and moments of reckoning—Skip Horner writes, “We suffer alone up there.” This slim book more than any other contributed to my understanding of the “why” of Everest. Climber Doug Scott tells us that “by the time we were above Camp VI, Dougal Haston and I had climbed beyond ego… for a time, I was lifted up above my usual state, being more aware of all and everything.”

Life and Death on Mt. Everest: Sherpas and Himalayan Mountaineering by Sherry B. Ortner

An integral part of the climbing experience for Western climbers involves their relationships with the Sherpas. In Life and Death on Mt. Everest: Sherpas and Himalayan Mountaineering, anthropologist Sherry B. Ortner lays bare the conundrums presented by Western dependence on Sherpa support in climbing Everest, and on the difficult choices facing the Sherpas who work for them. For instance, many Sherpas believe the mountain to be sacred and the very idea of climbing it violates their beliefs, yet they can earn nearly a year’s wages from one expedition. Are Sherpas ultimately exploited, or is the economic benefit to Sherpa families worth the risk? Can either Westerners or Sherpas fully “cross the cultural divide to form a mutually beneficial working relationship?”

Denali’s Howl by Andy Hall

Finally, you can find illumination about the drive to climb mountains and the dilemmas caused for those who must rescue them in a story much closer to home. Andy Hall’s Denali’s Howl is a page-turner with a unique perspective. It follows a 1969 expedition to North America’s highest peak: Denali to locals, Mt. McKinley to much of the country. The writer was the five-year-old son of the head of the park service charged with overseeing the climb as well as the search and rescue mission that ensued. Hall manages to give us fact and perspective without outright judgment. Still, he doesn’t shy away from entertaining questions about the responsibilities of the climbers as well as what can or should be done if they are in need of rescue.