- Katherine Cullerton, senior lecturer1,

- Jean Adams, professor2,

- Nita G Forouhi, professor2,

- Oliver Francis, head of communications and knowledge exchange2,

- Martin White, professor2

- 1School of Public Health, University of Queensland, Herston, QLD, Australia

- 2Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK

- Correspondence to: M White martin.white{at}mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk (or @martinwhite33 on Twitter)

- Accepted 7 November 2023

Poor diet is a growing global public health challenge contributing to increases in non-communicable diseases in all countries.1 The commercial food sector is widely recognised to shape consumer food environments, which in turn directly influence population diets.2 The commercial food sector’s impact on diets and non-communicable diseases represent a huge externality—that is, a cost generated by industry but borne by other sectors.3 Achieving healthier diets in populations to reduce non-communicable diseases requires actions by the commercial food sector, but evidence suggests that these actions are unlikely to happen without external pressure.4 Nevertheless, research funding bodies and institutions are increasingly encouraging researchers to work with the commercial food sector to identify solutions to prevailing problems in the food system.56

However, the primary goals of the commercial food sector and population health researchers might not be well aligned.3 This misalignment of purpose can create challenges if the two groups engage in research together, leading to conflicts of interest. Conflicts of interest are defined as “situations where an individual has an obligation to serve a party or perform a role and the individual has [either incentives or conflicting loyalties], which encourage the individual to act in ways that breach his or her obligations.”7 Furthermore, some elements within the commercial food sector engage in well documented tactics to influence research outcomes and public policy (eg, specifying the design and conduct of research) and could include practices regarded as unethical (eg, preventing publication of unfavourable results).891011 Any interaction between researchers and the commercial food sector therefore needs careful consideration, because it can undermine the credibility of research and researchers, resulting in an erosion of trust among the public and policy makers, and scepticism of published research.1213 Furthermore, such interactions can result in biased research distorting the evidence base and might enable the commercial food sector to influence public health policy makers.1415

The commercial food sector is diverse, ranging from farmers to transnational food corporations; therefore, the range of potential for goal misalignment with population health and associated research is broad. Interactions between researchers and the commercial food sector can thus result in a diverse set of outcomes, including those carrying none to high levels of research bias and reputational risk.1617 With scarce government funding for research in many countries and the potential to positively influence practices within the food industry, researchers are asking for guidance on ways to interact to minimise risk of reputational or other consequences.1819

While guidance on interacting with the commercial food sector exists for governments and non-government organisations2021 and for dietary guideline development committees,22 no internationally agreed guidance currently exists for population health researchers. These researchers often have different research needs from clinical research when interacting with the food industry—for example, evaluating whether changes to a supermarket will result in an increase in healthier purchasing,23 or whether a restaurant adding a levy to sugary drinks will sell fewer drinks.24 Both examples rely on in-kind support from the food industry. The absence of guidance has given rise to disagreements about acceptable levels and types of interaction. To resolve these tensions, we set about a programme of research and international consensus building to develop clear guidance to help researchers navigate this terrain, assess opportunities to interact with the commercial food sector, and prevent and manage conflicts of interest.

Summary points

-

Interacting with commercial food companies can result in conflicts of interest for population health researchers, which can bias research findings and contribute to reputational risks

-

By developing consensus on established principles for clarifying and negotiating these challenges, guidance and a toolkit has been developed that support principled decision making in population health research

-

The FoRK guidance and toolkit is a practical tool for researchers, research funders, and academic journals; its widespread use is encouraged in everyday practice and evaluation over time to refine and improve the guidance and toolkit

Aims and scope of the FoRK guidance and toolkit

The Food Research Risk (FoRK) guidance and toolkit aims to support researchers in making decisions about whether and how to interact with commercial food sector organisations at all stages of the research process. The FoRK tools aim to reduce risks to scientific integrity by exploring the potential for conflicts of interest in interactions with commercial organisations, revealing the implications of different kinds of interaction. The guidance and toolkit thus support thinking and dialogue on this issue, while also guiding decision making.

We designed the FoRK toolkit for researchers working in population level nutritional epidemiology, public health nutrition, dietary public health, and food policy evaluation (termed through this article as population health researchers). This relatively narrow focus was chosen because researchers whose focus is whole populations have research interests that can differ from those of clinical or laboratory based scientists. In population health, the main point of concern is promoting and protecting the health of the entire population.25 Public policy, including regulation, is often a key focus. Such policies are often poorly aligned with the goals of the commercial food sector.3 Consequently, scientific evidence generated by population health researchers regularly underpins government actions that are contrary to the preferences of the commercial sector. Undertaking research to prevent disease and promote health could therefore result in conflicts with commercial food sector organisations whose products have been associated with a raised risk of diet related health conditions.

The FoRK guidance and toolkit should both increase the capacity of population health researchers to assess risk when considering opportunities to interact with the commercial food sector, and guide researchers in managing those relationships if interaction proceeds. Notably, the definition of conflict of interest above26 has the concept of risk at the heart of it. When we refer to risk, we are referring to risk from conflicts of interest, which can not only result in biased research, but also reputational risk to individual researchers and research institutions, all of which might lead to public mistrust of science.27

The FoRK guidance and toolkit are not designed to be used to assess and guide policy making activities, because the primary interests and challenges of governments and policy officers are different from the primary interests of researchers, and other guidance is available assist in this area.21

Development of the FoRK guidance and toolkit

The FoRK guidance and toolkit were developed using a systematic, iterative process. We began with an event in 2015 for a diverse group of academic experts, debating the principles of how to engage the commercial food sector in population health research to serve the public interest.28 This event was followed by a systematic scoping review to identify the principles that have been used or proposed to govern interactions between the commercial food sector and population health researchers.29 The principles identified in the review then formed the basis of a two stage Delphi study of population health researchers to identify and build consensus on these key principles; and a survey of relevant, non-academic stakeholders, to identify their views on the principles.19

While these studies identified key areas of consensus among researchers (ie, research governance, transparency, and publication), areas of disagreement remained. The principles that had the highest level of disagreement related to which commercial sector food organisations were considered by population health researchers to be appropriate to interact with, and whether interactions should involve accepting direct funding, attending industry sponsored events, or accepting in-kind funding.

We convened an international workshop to resolve the issues in April 2018. Forty one population health researchers from high, middle, and low income countries came together for two days in an independently facilitated event. We aimed to achieve clarity regarding minimising risks arising from interactions with the commercial food sector. Participants included leading figures in the specialty as well as early and mid-career researchers. The researchers represented the full breadth of interests at which the guidance is aimed. Participants also had a range of experiences of interacting with the commercial food sector, ranging from no contact at all (n=30, 73%) to actively collaborating (n=2, 5%) or receiving research grants from the commercial food sector (n=9, 22%).

A range of issues was considered, with most of the workshop involving in-depth discussion of five themes identified from our previous research1929 relevant to preventing or managing conflicts of interest: publication, transparency, research governance, funding, and risk assessment. The development of overarching guidance and associated tools to aid decision making throughout the research process received strong support, particularly in relation to risk assessment of potential commercial food sector organisations and governance of research processes, including protocol development, implementation of fieldwork and analysis, and publication.

Drawing on the published literature identified in our systematic review29 and the feedback from the workshop, draft guidance with a series of thinking tools was developed. We completed three rounds of pilot testing incorporating feedback at each stage. This process began with eight different researchers or research groups piloting the initial tool. We then asked all 41 workshop participants to pilot the tool further using a real life example. Twenty one participants provided feedback. Finally, 12 researchers from a range of countries, who had not been involved in the workshop, piloted the guidance.

In developing this guidance, we involved people from across the spectrum of interacting with the commercial food sector, including those who strongly believe that risks outweigh benefits and vice versa. As a result, during the consensus building process, some participants stated that the guidance was too lenient and others stated that it was too restrictive.

Our primary objective is to ensure the integrity of science, and we believe we have achieved a fair and balanced approach in the guidance. However, few absolutes exist in this area. Opinions on these issues are likely to vary according to personal and institutional preferences, as well as ethical and political stances on a wide range of related issues (eg, the morality of wealth and profit). We anticipate that the guidance and toolkit will be refined and developed in accordance with scientific and ethical principles over time. Ultimately, the guidance and toolkit are not prescriptive, but thinking tools should allow researchers to make informed decisions about how to act with integrity, so they should be of value to a wide range of researchers.

Components of the FoRK guidance and toolkit

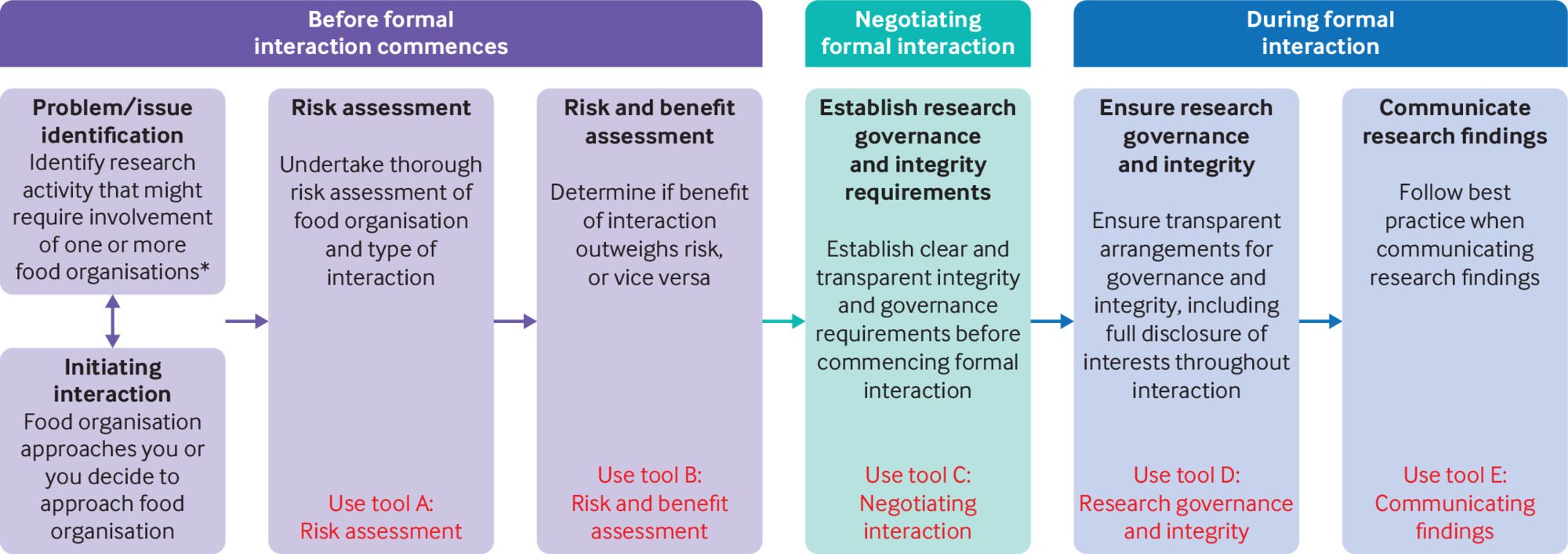

Box 1 lists the sections of the FoRK toolkit, which includes a flowchart (fig 1), guidance document, and tools A to E. The specific tools and guidance can be found in the supplementary materials.

Food Research Risk toolkit components

-

Flowchart that summarises which tools should be used at which stages of the research process (fig 1)

-

Guidance document, which sets out in detail how to use tools A and B and the evidence that underpins them

-

Tool A, part 1: assesses the risk profile of commercial food companies and associated organisations

-

Tool A, part 2: assesses the risks of different types of interactions with commercial food companies and associated organisations

-

Tool B: enables an overall risk-benefit analysis for specific interactions

-

Tool C: guides negotiations with commercial food companies or associated organisations concerning specific interactions

-

Tool D: guides research governance requirements for interactions involving commercial food companies or associated organisations

-

Tool E: guides the communication of findings from research involving interactions with commercial food companies or associated organisations

RETURN TO TEXT

Flowchart summarising which Food Research Risk tools should be used during the research process. *“Food organisation” includes both food and beverage companies and other closely associated organisations (eg, philanthropic foundations funded by the food industry, food and beverage retailers, trade associations or research institutes funded by the organisation or organisations)

“>

Flowchart summarising which Food Research Risk tools should be used during the research process. *“Food organisation” includes both food and beverage companies and other closely associated organisations (eg, philanthropic foundations funded by the food industry, food and beverage retailers, trade associations or research institutes funded by the organisation or organisations)

How to use the FoRK guidance and toolkit

Here, we briefly summarise how the FoRK guidance and toolkit should be used. Figure 1 illustrates the stages of the research process at which each tool should be used. We encourage researchers to use the toolkit when they are first considering interacting with a commercial food sector organisation (eg, a food company, a trade association, or industry funded think tank). Familiarisation with the challenges of safely interacting with such organisations, as well as the kinds of information needed to make decisions, will help researchers use the tools effectively. The toolkit is divided into two parts. Tools A and B are intended to help researchers decide about interacting with a commercial food sector organisation, whereas tools C-E are intended to support decision making among researchers committed to working with a commercial food sector organisation. Tools C-E thus aim to minimise the negative impacts of an interaction on scientific integrity.

We recommend that researchers start by using tool A, part 1 when they are thinking about interacting with a commercial food sector organisation. This tool takes researchers through several questions that will help achieve clarity on whether to interact with an organisation (including circumstances under which interaction might or should be avoided), and if proceeding with industry interaction, how to minimise the risk of undue industry influence. The tool focuses in particular on the levels of risk associated with different types of organisations. Tool A, part 2 goes a step further by exploring the types of interactions that are envisaged and helps researchers to assess the risks and benefits of each. The two parts of tool A enable researchers to see that there are greater risks to research integrity associated with some types of organisation and interaction. Through a systematic process, completing these tools will help researchers to decide the level of risk they are prepared to accept for anticipated benefits. Tool B brings together the risk and benefit assessments completed in tool A to provide an overall assessment. While such an overall score is ultimately arbitrary, it provides a helpful guide to the overall level of risk for researchers to consider before proceeding.

Risk assessments are inherently difficult because people tend to be overconfident about their ability to independently assess risk and the range of outcomes that might occur.3031 Ideally, the risk assessment (tools A and B) should be undertaken by one or more (independent) professional colleagues with whom the researcher does not work with directly.

If researchers have committed to an interaction with a commercial food sector organisation, then tools C-E will support their decision making with respect to negotiating interactions, research governance, and the communication of findings respectively. We recommend that these tools are completed at the earliest suitable stage of the interaction and then reviewed at regular intervals to maximise their impact on the whole process.

We encourage researchers who do engage with the commercial food sector to complete all tools and publish their risk assessments alongside their research, similar to the way in which other reporting guidelines are used (eg, STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) and other checklists). We recommend that journals and research funders also adopt the toolkit and recommend its use to their authors and funding applicants, respectively.

To illustrate how the tools can aid decision making among researchers, four examples of different kinds of interactions with commercial food sector organisations are described in table 1. We encourage researchers using the toolkit to provide their own examples in this format, and if possible with citations, via a form on the FoRK Toolkit webpage: https://www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/research/studies/diet-research-food-industry/. We also invite feedback on the toolkit, which will enable researchers to learn from other experiences and facilitate the refinement of the FoRK guidance and toolkit over time.

Use of the Food Research Risk toolkit to assess risks of proceeding with an interaction with a commercial entity—illustrative examples

Strengths and limitations

The principles embodied in the tools were derived from a systematic review of existing research and other scholarly contributions, on which we derived partial consensus through a formal Delphi process.1929 Further rigour was attained by convening an independently facilitated, two day workshop of international experts, at which additional consensus was achieved about the principles and agreement reached on the format of the guidance and toolkit. Finally, piloting of prototype versions of the guidance and toolkit by experts provided detailed feedback enabling modifications to improve comprehension and usefulness. Nevertheless, the guidance and toolkit would benefit from further field testing and feedback to determine their strengths and limitations, and to facilitate continuous improvement. Concepts within the guidance and toolkit could apply to other research fields within healthcare or population health and could also be adapted to assess interactions between researchers and public sector or non-governmental organisations. We encourage users to test the materials and provide feedback to the authors so that we can refine them and improve their usefulness.

Empirical work in this specialty is limited, and therefore many subjective judgments had to be made in developing the materials, particularly the risk assessment tool. Through multiple rounds of piloting, we attempted to strengthen the scoring methodology. However, we acknowledge its subjective nature, and emphasise that there are no right or wrong answers; the decisions made by researchers as a result will necessarily involve a degree of personal judgment, informed by the principles set out in the guidance. We acknowledge that no single solution exists to resolve the challenges posed by conflicts of interest in population health research of the commercial food sector, but we anticipate that using the FoRK guidance and toolkit will be an important step in achieving clarity of thought and transparency of actions and reporting.

While these tools assist and guide individual research teams to make decisions about industry interactions, they do not deal with broader concerns about the involvement of the commercial food sector in research. An example of such a concern is the systemic focus of industry funded research on industry friendly topics, such as studies about nutrients and production styles.11 Further concerns include funding of guideline committee members, advocacy groups, and journals by the commercial food sector.33 These strategies put researchers at risk of influence from the commercial food sector, often without the researchers realising it. Further work is needed to address these concerns.

Lastly, we acknowledge that we are likely to have implicit biases. We have attempted to make ourselves aware of these and approached the research with reflexivity by frequently acknowledging our own biases throughout the research, using an independent external facilitator at the international consensus meeting and gaining perspectives from many researchers throughout the research process. Nevertheless, we think that the FoRK toolkit can be improved over time, and welcome feedback via the toolkit web page (https://www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/research/studies/diet-research-food-industry/).

Conclusions

Through a systematic process of evidence synthesis, consensus building, and evidence informed design and piloting, we developed the FoRK guidance and toolkit to help population health researchers decide whether and how to interact with commercial food sector organisations. We encourage researchers to use and critically reflect on the materials, and to contribute to continual improvement of the toolkit. The materials could provide a template that can be adapted to guide interactions between other researchers and other commercial sectors, as well as non-commercial organisations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the researchers who provided feedback on this toolkit by either attending the consensus building workshop in Cambridge in 2018 or subsequently pilot testing the toolkit: Richmond Areetey, University of Ghana, Ghana; Gary Sacks, Deakin University, Australia; Amanda Wood, Stockholm Resilience Centre, Sweden; Ali Dhansey, South African Medical Research Council, South Africa; Christina Vogel, City University, London, UK; Cliona Ni Murchu, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Sean Cash, Tufts University, USA; Lana Vanderlee, Laval University, Canada; Steven Cummins, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK; Megan Ferguson, University of Queensland, Australia; Tarra Penney, York University, Canada; Kelly Brownell, Duke University, USA; Dianne Finegood, Simon Fraser University, Canada; Mary Yannakoulia, Harokopio University, Greece; Marita Hennessy, University College Cork, Ireland; Jeff Collin, Edinburgh University, UK; Angela Carriedo, World Public Health Nutrition Association, Bath University, UK; Ian Macdonald, Nottingham University, UK; Mike Rayner, Oxford University, UK; Fiona Gillison, Bath University, UK; Joreintje Mackenbach-van Es, Amsterdam UMC, Netherlands; Naason Maani, University of Edinburgh, UK; Oliver Mytton, University College London, UK; Shu Wen Ng, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA; Kaleab Baye, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia; Julie Brimblecombe, Monash University, Australia; Salome Antonette Rebello, National University of Singapore, Singapore; Janis Baird, University of Southampton, UK; Stefanie Vandevijvere, Sciensano, Belgium; Federico J A Perez-Cueto, Umeå University, Sweden; Margaret Miller, World Public Health Nutrition Association, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia.

Footnotes

-

Contributors: Fieldwork was undertaken by KC, supported by MW. All authors contributed to the development of the proposals for the research, securing funding, activities of the research, interpretation of data, and development of the guidance and toolkit. KC and MW led the writing of this article. All authors made substantive intellectual contributions to all aspects of the research and writing of this article, and approved the final version. MW is guarantor for the work. KC is a public health nutritionist and policy researcher; JA is a public health researcher and policy evaluator; NGF is a public health doctor, nutritional epidemiologist, and National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) senior investigator and acknowledges support from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) Epidemiology Unit (grant MC/UU/00006/3); OF is a communications and knowledge exchange expert; MW is a public health doctor, food systems expert, and policy evaluator. Further sources of information that have contributed to the guidance and toolkit are set out in the main text above. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

-

Funding: This article is the result of research funded by the UK Medical Research Council (grant MC/UU/00006/7). The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

-

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: all authors had financial support from the MRC for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

-

Patient and public involvement: We received no funding for public involvement and did not involve patients or the public because the study was focused on developing specific guidance for researchers concerning conflicts of interest with industry. As a result, no patients or members of the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

-

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: All participants in the workshop and involved in the pilot testing of the toolkit will be sent a copy of the published manuscript. We will present this work at scientific conferences and to professional groups. We have also developed a plain language summary of findings that is available on the project website, together with a form to provide feedback on the guidance and toolkit.

-

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.