Donald Trump is heading to Michigan to woo striking car-workers, a day after President Joe Biden turned up on the picket line in the Midwestern state – an early skirmish in the battle for the blue-collar vote ahead of next year’s White House election.

The former president is skipping tonight’s televised Republican debate over in California to deliver primetime remarks at a non-unionised car parts supplier just outside Detroit.

On Tuesday, Mr Biden’s glad-handing of United Auto Workers (UAW) members, also near Motor City, was a first for a sitting US president during a strike in modern times.

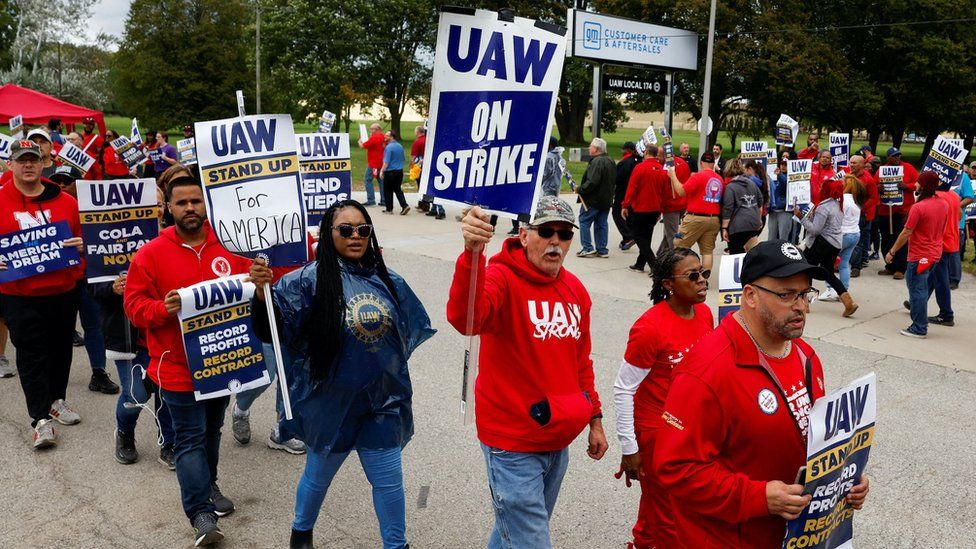

But clusters of red-shirted car workers on the picket line in the Detroit suburb of Wayne on Wednesday had few illusions about what’s driving these back-to-back visits by the two men most likely to contest the 2024 polls.

One of the striking car workers at Ford, 38-year-old Tony Branner, said he had voted for neither candidate in 2020.

He told the BBC he had not been paying much attention to the election campaign so far.

But with the two rivals practically at his doorstep, he was ready to listen.

“Whoever is fighting to help my job be better, I will support,” he said. “I’m interested in what both of them have to say.”

Mr Trump’s visit provides a perfect example of how dramatically he has reshaped American politics. The traditional labels of left and right don’t fit anymore.

He has succeeded in winning over many, mostly white, working-class voters who felt economically left behind and ignored by mainstream politicians.

After the 2020 election, exit polls showed Mr Trump winning more than four in 10 union members – that’s more than any other Republican for generations.

He will argue in his remarks on Wednesday evening that manufacturing workers will be better off under another Trump presidency.

He will assail Mr Biden’s efforts to tilt the industry towards electric vehicles (EVs). It takes far fewer workers to build battery-operated cars than those with combustion engines.

Concerns about the Democratic president’s push to phase out petrol-powered cars has provided further inroads for Mr Trump among union workers.

“He’s [Biden is] threatening the auto industry with EVs,” said car worker Kevin Puckett, who voted for Mr Trump in 2016 and 2020, and expects to do so again.

“To mandate them and go full steam ahead – it’s putting the car companies in a bad way.”

As Mr Biden cautiously endorses the car workers’ demands for a 40% pay rise, Mr Trump wrote on his social media platform in an all-capital-letters post to union workers: “I will keep your jobs and make you rich.”

Though unemployment remains low and wages are rising, American voters’ dissatisfaction over the economy remains high.

The issue, driven by stubborn price inflation, is underscored by the strike.

Mr Biden has cast himself as the most pro-union president in history.

He has installed pro-labour officials at key regulatory bodies, such as the National Labor Relations Board.

Mr Biden has also backed provisions in his signature spending bills encouraging the use of made-in-America materials and requiring companies that receive federal money to offer certain levels of pay.

But on the picket line, he is still seen by some as suspect.

He used his power last year to block a potential strike by freight rail workers. And he cancelled the Keystone XL oil pipeline, drawing criticism from unions worried about lost jobs.

Much of Mr Biden’s action has been symbolic: messages of support, like the appearance in Michigan this week.

But for Biden supporter Lillian Dunson, one of hundreds of workers put on temporary layoff by Ford after the strike began on 15 September, those kinds of gestures were important.

“I believe that he [Mr Biden] feels what we feel, what the people feel – that he’s not just a billionaire,” she said.

“He’s disingenuous,” she added of Mr Trump, noting he remained on the side lines in 2019, the last time car workers went on strike.

During Mr Trump’s presidency, the National Labor Relations Board reversed several Obama-era rulings that had made it easier for small unions to organise.

The Republican calls himself pro-worker, reflecting a conservative belief that unions make businesses less competitive, ultimately hurting employees.

Mr Trump – who is visiting Michigan without a union invite, unlike Mr Biden – has been critical of the UAW leadership in this strike.

But though the union’s president, Shawn Fain, has been less than complimentary of Mr Trump, he has also withheld an endorsement of Mr Biden’s bid for re-election.

Some car workers said it was hard not to be seduced by Mr Trump’s call to Make America Great Again.

As recently as the 1990s, the average worker in the industry commanded some of the highest pay in the country.

But that guarantee of a comfortable middle-class life has steadily eroded.

“I think we do need to take care of our own first,” said Curtis Cranford, who has worked in the industry since 1985 and backed Mr Trump in 2016 and 2020.

He was rueful about his decision, noting what he described as “personal” shortcomings by Mr Trump, who has been found liable by courts for business fraud, defamation and sexual assault.

Mr Cranford was among a handful of workers who exchanged fist bumps with Mr Biden this week. He said the Democratic president seemed “sincere”.

But he expressed disappointment with the White House’s handling of issues such as immigration and inflation.

He is also concerned about money being spent to support Ukraine, and feels divided from Democrats on issues such as abortion.

“I really don’t want to vote for [Mr Trump], but if he’s the only Republican standing, then I probably would,” he said.

Mr Trump won Michigan in a surprise victory in 2016. Mr Biden reclaimed the Great Lakes State four years later.

Democrats solidified their gains in midterm elections last year.

But the conflicting political views on the picket line suggest this Rust Belt state, which could hold the keys to the White House next year, is still very much contested territory.