If there is one thing we know for sure in the current age of information it is that culture is a living breathing entity.

In his new book, Culture: The Story of Us, from Cave Art to K-Pop, released this month, Martin Puchner delves into the history and evolution of culture, providing ample context to the idea that it is and has always been symbiotic with everything around us.

“One could almost say that culture is curation because it’s all about selecting canons,” Puchner tells The National.

“We are saying this is important and this is not important. Curation is totally key. It’s what we decide to value. And then we can of course ask, who decides who’s in a position to curate?”

Puchner is a professor of English and comparative literature at Harvard University and a global fellow at Queen Mary University of London. He has written books ranging from philosophy to technology and the arts.

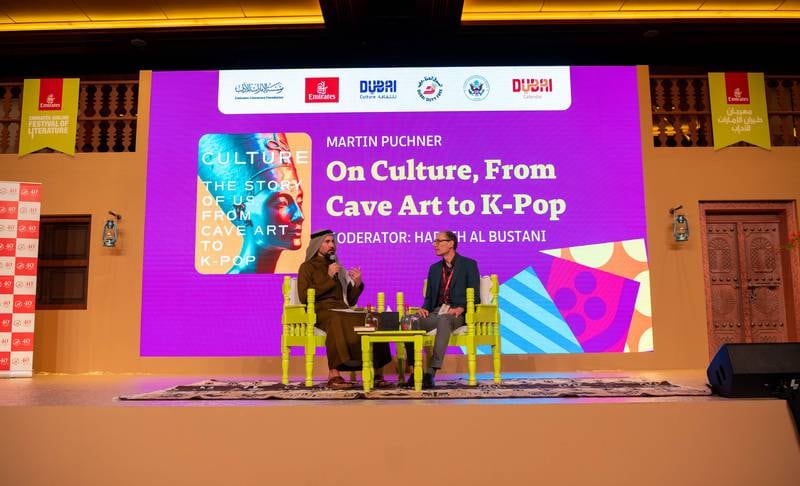

His latest book, which he introduced at this year’s Emirates Airline Festival of Literature, is a form of curating culture within itself. Through storytelling he delves into instances within the cultural framework moving across time and place.

From a statue of a South Asian goddess in the Roman city of Pompeii or the 7th century Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang who took a 16-year pilgrimage to India to translate and bring back scriptures, to the growth of Baghdad as a cultural hub and the formation of the House of Wisdom during the Islamic Golden Age, Puchner delivers story after story, revealing the influxes, vacuums and nuances of culture and how they affect our understanding of history and our present.

“I wanted to show the variety of forms of cultural contact,” he says. “I also wanted to show this rhythm of interruption and forgetting and loss and recovery.

“I got very interested in the moments when a remnant of our culture got frozen in place, either because the entrance to a prehistoric cave closes up or because of volcano – like in the case of Pompeii where an eruption destroys the city but also preserves it.”

Puchner elaborates that the constant rhythm of storing culture and attempting to preserve it for the next generation is a system that often breaks down or gets interrupted. Whether through natural disasters, wars, or other social changes, we are constantly confronted with the remnants of the past that we don’t completely understand, which simultaneously reshapes our view of ourselves.

There are many pivotal moments in world history that are represented through objects, architecture, art, literature and music. Many of them are preserved in museums and cultural institutions around the world – sometimes far away from the countries and cultures of their origins.

Restitution within the context of museums has been a pertinent and polarising topic in public discourse over the last several years. It’s a topic that put into focus, as Puchner points out, the idea of curating culture and who decides what, where and when to curate.

The return of cultural objects to individuals, communities or the countries they were taken from, opens up a debate on not only who should be telling the stories of the past, but also who “owns” culture. Puchner sees restitution as a fascinating, complicated discussion.

One of the main points brought up in debates in defence of not returning artefacts to their countries of origin, is the issue of safety. Puchner mentions Iraq as an example, where during the American invasion, the Iraqi Archaeological Museum in Baghdad was looted in April of 2003.

But Puchner also sees the disparity in this argument citing the bust of Nefertiti, of which he dedicates a whole chapter in his book. The ancient sculpture has been part of the Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection at the Neues Museum in Berlin, Germany since its public unveiling in 1924.

Arguably, the bust has faced extreme danger given that Berlin was at the centre of two world wars. The museum itself was bombed on November 1943, and again in February 1945. In both instances, the museum and some of its valuable collections were damaged.

“In the end, if you really want to make sure that something endures it’s probably best to leave it underground,” Puchner says.

“If you excavate something then you’re exposing it. You can guard it, you can try to build institutions and safeguard it, but we all know how quickly that can change anywhere in the world.”

A more comprehensive form of protecting cultural artefacts, Puchner says, is through education. “You have to instil in the next generation a sense that this is important to care about,” he says.

“Because more often than not, when something gets abandoned, it’s because of neglect, it’s not so much because of war. Things get lost because cultures lose interest in them and they get neglected and if you neglect something, it tends to fall by the wayside.”

The UAE and the greater region have been focused over the last five years at least on doing just that. Whether its building museums, institutions and ecosystems to promote and educate the public on local and regional art, culture and heritage, Puchner says it’s exciting to see how the UAE will present itself and its history to the world.

“It will be so interesting to see how that activity will change the region’s sense of itself and its own history,” he says.

“The Arabian Peninsula has always been such a trade route among different cultures that it will also add an important chapter or deepen our understanding of the rich history of cultural exchange, which is something that I’m so interested in seeing.”

Updated: February 08, 2024, 2:03 PM