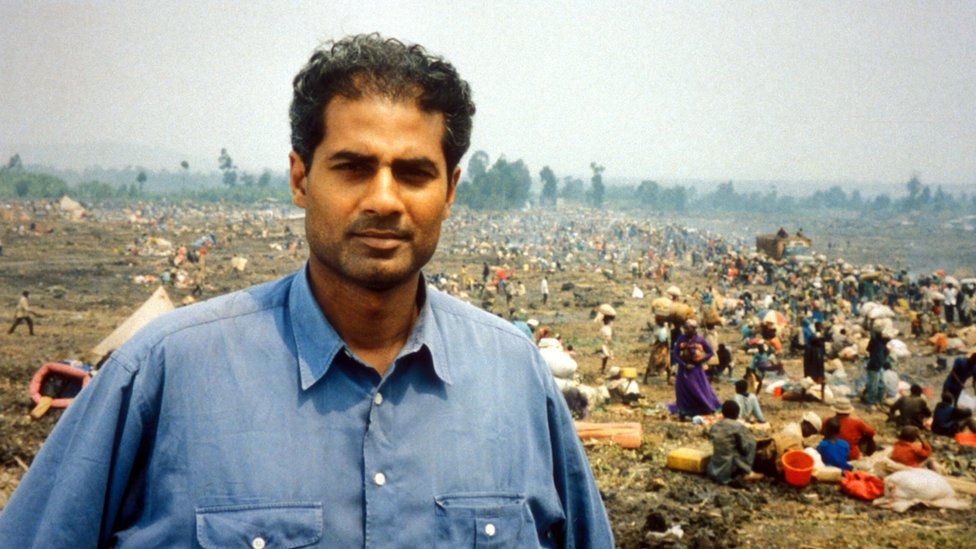

George Alagiah, who has died aged 67, was one of the BBC’s longest-serving and most respected journalists. Being a friend and colleague of the award-winning foreign correspondent was a privilege – writes Allan Little.

George and I were thrown together when we shared an office in Johannesburg in the Mandela years. So when I think of him I see him not in a television studio in London but on some red dust road, bathed in the light of Africa.

Empathy was his great strength. He radiated it. It was rooted in the deepest respect for the people whose lives and – often – misfortunes he was reporting on. He could talk to anyone – from heads of state to children in a refugee camp on the edge of a war zone. And everyone wanted to talk to him. You saw him winning their trust, responding to his effortless warmth. He wanted to do well by all of them – to be true and honest and fair.

Once we sheltered in a stairwell, after three mortar bombs landed close to the hotel we were staying in Central Africa. A colleague reported that heavy shelling had, as they put it, rocked the city centre. Later, George said to me quietly “Allan don’t say that. Heavy shelling didn’t rock anything tonight. Three bombs fell close to where we happened to be and gave us a fright. Keep it in proportion.” And I thought, not for the first time, “My name is George Alagiah and I’m here to calm you down.” George didn’t want to be dramatic. He wanted to be true.

I came to understand that I was learning from him at a time when I was still trying to find my own distinctive broadcasting voice. What did I learn? That good reporting, honest and true, is rooted in respect for others. That the best reporters have almost no ego. That they are never the story, but the means by which the voices of others can be heard. I hoped that the values he embodied and lived would rub off on me.

George wasn’t just a good reporter; he was a good man. He was completely without malice. He carried his profound decency very lightly without a hint of sanctimony. He seemed unaware of his own instinct for kindness. When we worked in dangerous and morally troubling places, I looked to him for guidance. I loved his unflappability, his calm authority, his extraordinary wisdom. I thought of him as something like an older brother – someone I quietly looked up to, whose success I could admire and celebrate without envy. I’m not ashamed to say that I felt looked after by him. I thought when I was with George nothing bad could happen to me.

I am aware I am in danger of making him sound a bit saintly – he wasn’t. He was great fun. He could be a witty and sometimes hilarious raconteur – with a gift for sometimes merciless mimicry. And like all of us, he enjoyed a bit of intrigue and gossip.

There is a word in the Nguni languages of Southern Africa that was, I think, George’s lodestar. He spoke about it at a party to celebrate his 60th birthday in 2015: Ubuntu. It expresses the idea that human beings are bound together in a shared responsibility for each other.

George and I both interviewed Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who’d helped end South Africa’s racist system of white-minority rule. He defined Ubuntu like this: “I am me because you are you. I can never be free while you are enslaved. I can never be rich while you are poor. We two are connected.”

George had been a migrant twice by the age of 11. Born in Sri Lanka, moved to Ghana and then to a boarding school in England.

Adapting to new cultures and thriving were formative experiences. And it planted in him something that was also key to his talent: he could see how the world looked from the point of view of the Global South – the view from Africa and Asia especially – and convey that perspective to the living rooms of the globally prosperous.

George would never have made such a claim for himself. Off screen he was funny, clever, entertaining, a generous friend and confident. I told him once that the pan in companion came from the Latin word for bread, that the word carried in it the ingrained human desire to break bread with those we love and care about. He laughed and said, “How do you know these ridiculous things?” But I have had some of the richest experiences of companionability and conviviality at George’s table, breaking bread.

For George was also full of a kind of energetic hope. There was something infectious about his optimism. You always walked away from time with George liking the human race more, feeling better about the world.

He brought that cheerful disposition to his cancer diagnosis. I rang him when I heard the news. “It’s much worse than the public statement implies, Allan,” he confided. “But I have great doctors.”

Years later, when the cancer had returned and we knew it would never go away, I sat with him in the garden of the London home he shared with Frances, his wife of 40 years. “I’m not afraid to die,” he said. “There’s no point in that. The only thing I find unbearably painful is the idea of Frances being left here on her own.”

Always that in George. Others before self. I saw him one last time shortly before he died. He was very weak. “Is it wrong to say that there is something positive in all this?” he said. “I’ve had the time to reflect on my life and make sense of it. Time to say to people the things I want them to know. Not everybody is lucky enough to get that…

And the next word he used pierced me – and I still feel the sting of it: “Not everybody is lucky enough to get that luxury.” And he added in a moment of self-doubt: “Is it bad, is it taboo, to say that about cancer?”

I was guided by him, taught by him, at a key time in my own life. I think I will be guided by him all my days. Becoming his friend, being exposed to his abundant affection, has been one of the greatest privileges of my life.

Ubuntu: I watched George close up while working in Africa. I marvelled at the way he engaged with people, and the way they reciprocated with their trust.

For in George’s reporting there was an outstretched hand – the outstretched hand of a shared humanity, of solidarity.

Related Topics

- George Alagiah

- Ghana

- Obituaries

- Sri Lanka