Much attention has been paid in recent times to Australia’s over-reliance on American power for our national defence. But far more of our sovereignty has been eroded beneath us by far more insidious means: our extraordinary and increasing reliance on the United States, and China, for technology.

For individual citizens going about their day, for the critical infrastructure which enables the functioning of our society, and even our national defence, this weakness has now accelerated beyond the point of no return.

This vast technology gap has eaten deeply into Australia’s ability to determine its own path. In creating software, in the engineering of critical componentry and in the storage of sensitive data, this gulf is now so vast, it has become impossible to bridge. To endeavour to catch up to the US, for example, would cost so much as to be economic suicide, akin to trying to build a rival space or even nuclear weapons program.

The evidence of this slide into dependence is everywhere. As individuals, we are subjugated by our smartphones, none of which are designed, programmed or, least of all, manufactured here. Our national debates about privacy and surveillance are important but increasingly irrelevant, because those conducting the surveillance or dismantling our privacy are not here; they’re far away, and they’re governed by foreign law. The same is true of the systems which control our national infrastructure, from dams and energy grids, to banks and communication systems.

On the other side of the Pacific, US lawmakers are deeply concerned about the way companies like Google and Microsoft are increasingly governing the lives of Americans and stamping out competition. Efforts by Congress to regulate the sector have run up against a sophisticated lobbying campaign to prevent it doing so.

But at least America’s legislature is trying. Here, Australia’s parliament is sleepy and unconcerned.

“It amuses me to see Americans in a panic about the power and scale of big technology companies,” said David Elliot, head of Canberra software company Agile Digital. “They’re nervous … and yet they’re at the top of the pile.”‘

Loading…

The cold reality of what we’ve lost

Overwhelmed by the digital revolution, Elliot says Australia is losing the ability to even comprehend the technologies it is bringing in from overseas.

“We are becoming more and more dependent as our critical infrastructure becomes increasingly reliant on ‘black box’ technologies,” he said. “Once a society doesn’t understand how things work, it’s walking on the path towards magical thinking.”

The most recent, acute example of this technology dependence is the impact of Microsoft’s decision two years ago to withdraw much of its work for foreign governments, including ours.

Despite tendering to deliver a Top Secret cloud for the Australian government’s most sensitive data, then negotiating throughout 2021 with the Department of Defence and the Office of National Intelligence, Microsoft pulled the pin, with no warning, mid-way through 2022. To their credit, our officials had been demanding that Microsoft meet stringent criteria for local, sovereign control over our data.

The effect of Microsoft’s decision exposed our vulnerability and was damaging for a string of secretive projects. One is a $500 million data integration scheme being pursued by Defence, which began to fall fall apart after Microsoft quit.

The cold reality is that Australia may have already lost the ability to store its own data. Certainly, decision-makers believe they have little choice but to call upon the so-called “hyperscale” trio: Microsoft Azure, Amazon AWS or Google Cloud.

At a Senate Estimates hearing last week, Chris Crozier, Defence’s Chief Information Officer, admitted as much. Some overseas companies have become indispensable.

“Sovereign capability cannot provide hyperscale,” he said. “You’ve got to go to the global platforms”.

As consolation, he promised cameo roles for Australian firms. Vault Cloud, a local data storage company certified by the Australian Signals Directorate, is playing such a role; it picked up a $3 million contract with Defence after Microsoft’s sudden departure.

We don’t always get what we pay for

Vault Cloud’s boss, Rupert Taylor-Price, is among a group of Australian technology executives who have been vocal about Canberra’s growing dependency problem. He says complex components and software, designed and built overseas, increasingly control “everything from our water supply to the means by which we fire our missiles”.

“Many people have failed to grasp,” he said, “that if you lose the sovereignty of IT platforms you lose the sovereignty of your critical infrastructure.”

The peak of the Black Summer fires of 2020 offers another example.

With the country ablaze, authorities were alarmed to be told that their access to a global geosynchronous satellite program — to obtain real-time pictures of the fires which would eventually kill almost 500 people — would be subject to a 24-hour delay. Australia might have paid $1 billion for privileged access to the program, but, if you haven’t already guessed, it’s the US military which controls it.

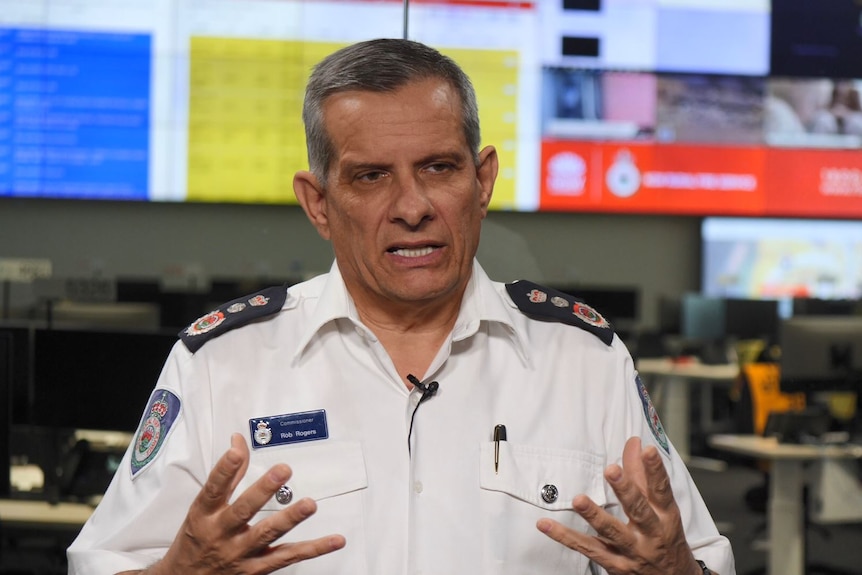

I asked Rob Rogers about the delay. He was then deputy commissioner of the NSW Rural Fire Service and is now its boss. He says it renders the satellite capacity “absolutely useless”.

“We also found that some of the trajectories of those satellites were not generous to us as a country and didn’t give us the amount of mapping they gave to parts of the United States.”

Defence is now procuring its own far-orbit satellites in a bid for sovereign control. No small irony then, that last year it gave the contract to US multinational Lockheed Martin.

AI isn’t made with us in mind

This impotence is only to become starker as artificial intelligence creeps into a greater and greater proportion of new technology, says Elliot.

“These technologies are largely trained overseas,” he said. “When you ask an AI a question it will generally compose an answer based on foreign training data, and we will likely not know what that data was or what bias is present in its answers.

“As we hand over our agency in decision-making to autonomous machines it’s becoming a more serious issue for our nation that we fully understand how they work.”

I stumbled over an extraordinary example of this recently, trawling aimlessly through a list of government transactions. The contract’s title is “AWS Generative Artificial Intelligence Discovery Proof of Concept on Parliamentary Submissions”, and its procurer is the corporate watchdog, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

Amazed, I asked for an explanation. In essence, ASIC said it is becoming too onerous to read public submissions to parliamentary inquiries — particularly the inquiry now investigating the Commonwealth’s use of the big four consulting firms.

“As the submissions grow, it becomes increasingly challenging with limited resources to read and summarise all submissions with a short turnaround,” ASIC’s spokeswoman told me. (In case you were wondering how many are too many, the current inquiry has 75 submissions on its website.)

“The ability of LLMs [Large Language Model AIs] to summarise documents quickly is well publicised and this activity suggests itself as an ideal and low risk way for ASIC to test the technology.”

Of course, this is only a trial, a so-called “proof of concept”, but a glimpse of the future nonetheless. Consider ASIC’s initiative through the prism of Elliot’s warning about bias: here, a vital public institution, the corporate cop no less, is seeking to rely on an overseas-trained, black-box technology, to filter the correspondence of citizens to their own parliament.

Loading

So what’s to be done?

No-one would sensibly advocate for trying to build a technological industrial base to compete with the US or China. But elsewhere, particularly in the European Union, this challenge is being met head-on by enterprising elected officials.

Together with the pursuit of antitrust cases against large technology firms, the EU has actively sought tough regulation on issues such as data storage. It is demanding the power to control the facilities and software which houses its information, as well as protections from notorious anti-competitive conduct. The big tech firms have had little choice but to accept it. Paris was so resolute, for example, that Google was forced to partner with French firm Thales to “co-develop” a local cloud service.

Back home, there are obvious fixes. At the minute, Australia has no laws which mandate that its data must be held onshore (with a minor exception for health information). And of the roughly $10 billion a year the Commonwealth spends on information technology, the majority flows straight offshore, much of it into tax havens. Surely more must be spent here?

Any change will be hard-won. As entrenched as they now are in Australian society, these companies won’t simply yield. When the Department of Home Affairs released a discussion paper on “data localisation” two years ago, Facebook, Apple, Twitter and Google immediately kicked back. The proposal has gathered dust ever since.

Attempts at genuine regulation will require not only an active parliament, but a government able to withstand intense lobbying — including, it should be pointed out, from the White House.