The incursion of artificial intelligence into the upper strata of the international art world is well under way. Last year, New York’s Museum of Modern Art anointed the Turkish artist and designer Refik Anadol as AI art’s avatar when his big-screen lobby installation “Unsupervised” attracted huge crowds. Anadol and his Los Angeles-based studio, founded in 2014, had created a large language model that marinated the metadata of MoMA’s vast artwork collection — spanning 150 years of art history in almost 140,000 items — and unspooled it into rapidly morphing evanescent forms and palettes. The piece alternated between hints of familiar canonical elements and completely new terrain, as well as including sensory input from the immediate public space.

Crowds were duly mesmerised, some viewers transfixed for an hour or more, peering into the “mind” of a deep-learning machine that imagined art in and between the category clusters of human efforts that preceded it, and produced art that might have been.

“This project reshapes the relationship between the physical and the virtual, the real and the unreal,” said co-curator Michelle Kuo. “Often, AI is used to classify, process and generate realistic representations of the world. Anadol’s work, by contrast, is visionary: it explores dreams, hallucination and irrationality, posing an alternate understanding of modern art — and of artmaking itself.”

Anadol’s journey started with Blade Runner. Born in 1985 and growing up in Istanbul, he watched Ridley Scott’s 1982 neo-noir classic at a tender age. He was jolted by a key scene between the film’s android leads, in which Rachael learns that her memories are actually someone else’s — contrived as components of a replicant’s machine mind. That concept imprinted on Anadol what would become his life’s work: exploring the apparently infinite terrain of what a machine imbued with “deep learning” can do with the artefacts of both personal and collective memory.

“Since that moment,” says Anadol, “one of my inspirations has been that question: what can a machine do with someone else’s memories?” He has since posed several other provocative queries, such as “If a machine can learn, can it hallucinate?” and coined novel concepts such as “data pigmentation” and “thinking brushes” to further nudge what may be a sci-fi-inflected strand of contemporary art into the rear-view thinking of the art world.

Anadol’s latest exhibition, Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, is currently on view at the Serpentine Galleries in London. Curated by the Serpentine’s artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist, it’s a multichannel immersive presentation of new and recent works about natural phenomena that create real-time alternative worlds.

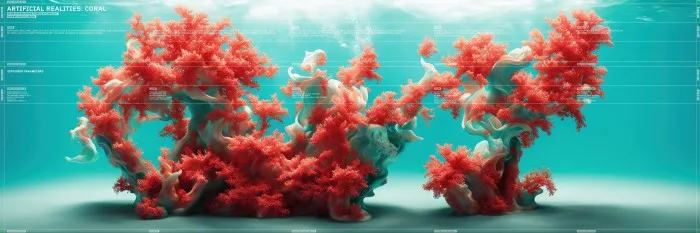

Among the works is “Artificial Realities: Coral” (2023), for which Anadol’s team trained a unique AI model on approximately 5bn images of corals publicly accessible online. The result is a ravishing profusion of abstracted corals, dreamt by Anadol’s tireless machine, that define an imaginary underwater habitat. The work addresses the climate crisis that is wreaking well-documented havoc on coral reefs everywhere, and suggests that AI might one day enable marine scientists to 3D-print replacement coral.

The show even includes a custom-made scent, conjured in Bulgari’s lab to Anadol’s specification, to enhance what is meant to be a full sensory experience. “Our hope is to bring together sound, image, text and scent. Four domains in one space,” he says.

The exhibition also features the UK premiere of “Living Archive: Nature”, first presented at the World Economic Forum 2024 at Davos in January, which has absorbed and transformed the soundscape and image data of flora, fauna and fungi from more than 16 rainforests across the world. Anadol’s collaboration with the indigenous Yawanawá people of Amazonia was particularly fruitful; they gave him and his wife special names for initiating a programme that brought in generous funding to rebuild their village.

The works on view are part of an ever-evolving enterprise inspired by what Anadol believes to be the singular common language of humanity — nature. “It’s not about replacing nature or making an alternative nature; it’s just about understanding nature, and doing it from scratch, with a new perspective. What I had found missing in all our earlier AI research was nature, which I have a deep love and respect for. So we set out to create the world’s most advanced open-source AI model on it, called Large Nature Model. And that is a gift to humanity.”

Anadol talks a lot about the collective over the personal. Not interested in the notion of a solitary artist wrestling with psychic demons or mining intellectual formalism, he seeks a universal language that transcends all identities, biases and boundaries — dreamscapes for the 21st century’s global human aggregate.

Architecture is central to Anadol’s practice. In a years-long dedication to adapting AI to architectural conception, he has worked with Frank Gehry and with the late Zaha Hadid’s firm. “I believe architecture is beyond concrete, steel and glass, and that when data and AI are combined purposefully with light as a material, there’s a whole new dimension that adds new meaning and purpose to built environments. One day buildings will learn, will dream and hallucinate.”

The grandeur of Anadol’s ambitions for artificial intelligence, and his undiluted optimism about its impact on creativity in general, can be contagious. His team has collaborated with philosophers, biologists, medical doctors, environmental scientists and computational designers working at the intersection of art, science and technology. He has engaged a neuroscientist to gauge the biological effects on viewers at the moment of experiencing his works — towards the goal of inducing meditative, healing and even spiritual states. He and his team loftily envision “the power not only to challenge but to change existing systems, to create a better world”.

A widespread concern about AI is the computer’s inability to exercise moral discretion. Data sets can contain prejudices — racism, misogyny, national or religious bias and so on — or unintentional human error or fudged scientific results, which the AI then crystallises and validates. For Anadol, it comes down to a workflow equation wherein the human remains morally empowered. For him, “the morality is in the data curation. It is in the DNA of the decision of how AI makes the artwork and from which materials. That’s why we always train our own AI. It traces back to these human decisions. The ethics are embedded in . . . AI research, not the AI itself. Maybe the most unbiased data is nature, which is why nature is my fundamental data source.”

To April 7, serpentinegalleries.org