The ruined temples and palaces of south India’s Vijayanagar empire rise from an enigmatic landscape of giant boulders and banana groves in Karnataka state. The last great Hindu kingdom — one of the richest cities of its day — was founded in the 1330s on a lush river whose granite banks formed a natural fortress. Yet its capital was vanquished and abandoned in 1565. A Unesco World Heritage site since 1986, the partially excavated imperial capital with pyramidal temples, 200 miles east of Goa, is now known as Hampi after the village that sprang from its ruins.

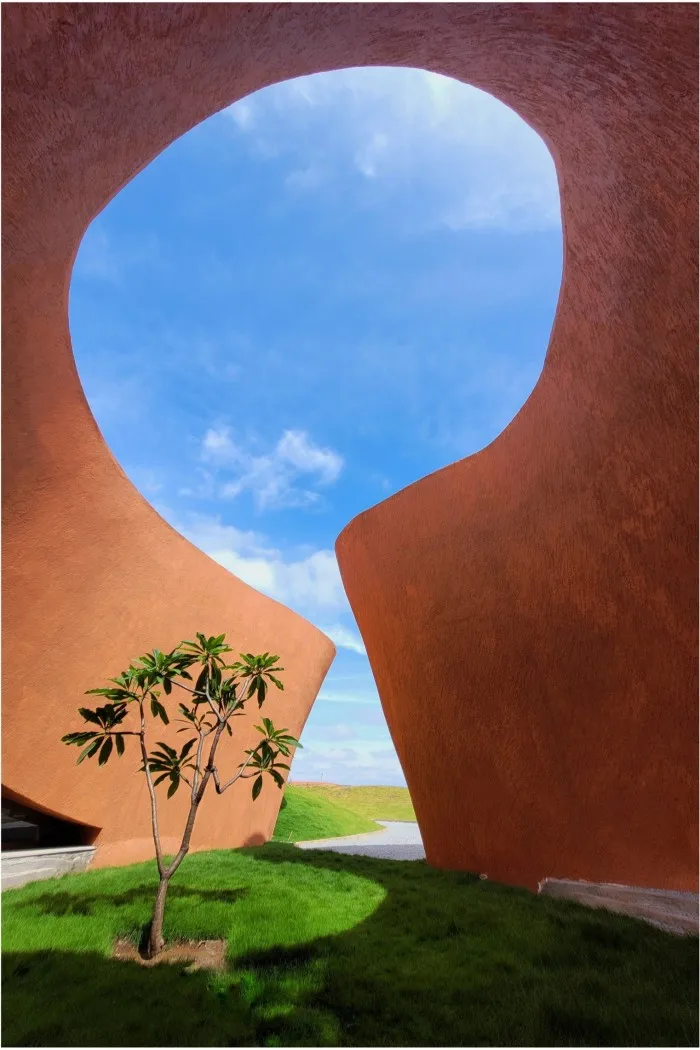

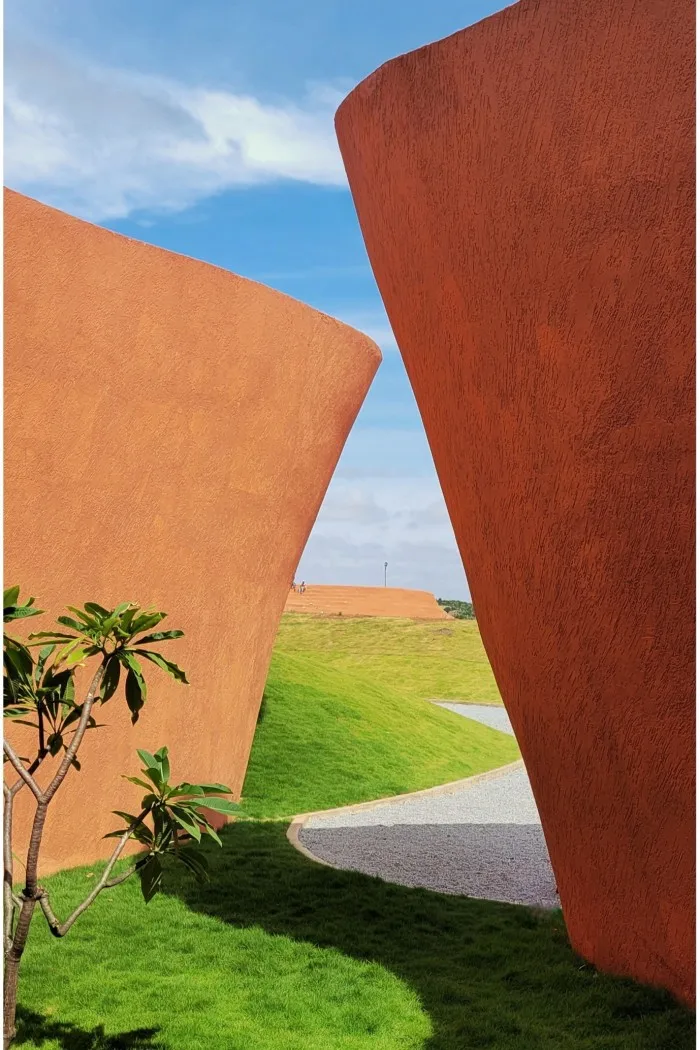

Less than an hour’s drive away, a low-rise, mud-red building, whose flowing contours recall the Tungabhadra river, was inaugurated in February as an ambitious centre for contemporary art-making in south Asia. It draws inspiration from the Dravidian ruins mourned in VS Naipaul’s India: A Wounded Civilisation (1977) and conjured from epic poetry in Salman Rushdie’s novel Victory City (2023).

This rocky landscape is also revered as the realm of Hanuman, the Ramayana’s monkey god, whose long-tailed image is ubiquitous on the temples — watched by mischievous real-life descendants. Yet Hampi Art Labs is the latest addition to an art infrastructure fuelled by a booming modern economy. It follows the private, interactive Museum of Art and Photography (MAP) that opened last year in nearby Bengaluru, India’s silicon valley.

An artists’ retreat with spacious studios and designer living quarters, Hampi Art Labs also has a public gallery and café. Its flat roof — inspired by Oslo’s Opera House — is being planted with kitchen gardens. The Mumbai-based architect, Sameep Padora, used local granite and teak along with another material synonymous with the area: steel. A sign at the local airport reads: “Welcome to Vijayanagar Steel City.” India’s biggest integrated steel manufacturing plant was founded a quarter of a century ago on arid land above a belt of iron ore. “From soil to coil”, its mined ore progresses via rubber pipes, red-hot blast furnaces, molten channels and railways to emerge as coiled steel.

The steelworks’ chimneys are in view of the Art Labs, which are funded by the JSW Foundation created by the Jindal steel family. The art centre stands at the gateway of a sprawling model township built for steelworks employees. With this unusual synergy, the hope is that visiting artists will not only be inspired by Hampi’s heritage and landscape, but will access the mammoth industrial plant on their doorstep to create costly, large-scale sculptures and installations beyond the dreams of most artists in south Asia.

Visiting Hampi two decades ago “was my first memory of being awestruck by sculpture”, Anirudh Shaktawat, an Udaipur-based sculptor among the first five artists on a three-month residency, tells me. Yet he is as inspired by the steel plant’s “geological process — lava bursting from the core, like massive witches’ cauldrons”. Having just had a show in a commercial gallery in Mumbai, and planning to scale up, he embraces the “shift from a gallery to a more experimental space where there are no restrictions: we don’t necessarily have to provide things that sell.”

This model of enlightened patronage may owe something to Vijayanagar’s 16th-century poet-king Krishnadevaraya, who ploughed the empire’s fabulous wealth — in sandalwood, spices, diamonds and horses (even the elephant stables were palatial) — into sculptors, painters, writers and architects. Despite these parallels, for Sangita Jindal, chair of the JSW Foundation and founder of Hampi Art Labs, a closer model is her mother, Urmila Kanoria, who created one of India’s first artists’ residencies in Gujarat 40 years ago. “I saw my mother struggling because she didn’t have the resources I have,” Jindal tells me. “I saw her pain, and her happiness, and realised this is a place I have access to.”

Jindal, who grew up in Kolkata, came to this 10,000-acre site in Karnataka “with my husband, to build the steel plant, so I got to know this old land of rich Karnatak music,” once written on palm leaves. “I realised heritage is a form of art, and a root of new forms. I wanted Hampi Art Labs to be in ancient Hampi as an inspiration.”

Since 2000, her foundation has helped conserve Hindu temples that were destroyed by a Muslim confederacy, at a time when religious architecture is being weaponised for political ends. Yet for Jindal, “Hampi is not about religion. There are only two living temples; the rest are ruins.” She has also restored a synagogue in Mumbai. “I’ll restore mosques as well.”

One Hampi temple may have been spared from conquerors’ torches by its Indo-Islamic arches — testament to the hybrid architecture of a pluralist empire. “Two cultures merged and coexisted,” says Promiti Hossain, a Bangladeshi artist based in Santiniketan, West Bengal. Her watercolour-and-ink drawings reference imperial history. With the trauma of invasions arose “new artistic techniques”, she says. Islamic powers “stayed and introduced their craft and sculpture. It’s not the same as colonial impact, when so much was taken from us.”

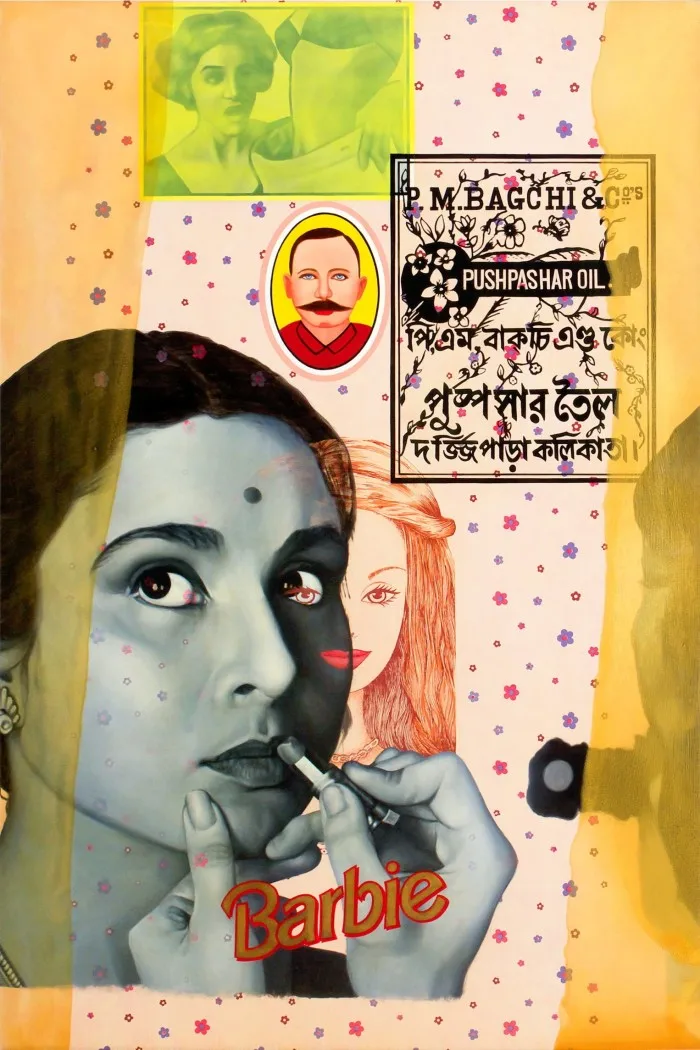

This history is partially explored in the township’s Kaladham art village, founded in 2012, whose multimedia museum has images of a famous stone chariot pulled by sculpted elephants in Hampi, where friezes depict Chinese, Arab and Portuguese traders who visited. Like the museum, the Art Labs are meant to serve the township’s population, with two exhibitions a year. The inaugural show Right Foot First — its title from a Hindu belief about crossing thresholds — shows works from Jindal’s art collection of 1998-2023, from Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei to Praneet Soi and Atul Dodiya.

“To promote Indian art is our focus and mandate,” Tarini Jindal Handa, Jindal’s daughter and creative director of Hampi Art Labs, tells me. The aim is that the residency be “80 per cent for Indian artists”, with a further focus on south Asia. Partnerships are planned with the Delfina Foundation and the Institut Français. The urban location of most artists’ residences in India, Handa says, restricts their scale. Here, there are production facilities for printmaking, 3D printing, sculpting in metal and stone, and ceramics — including local black ware made of iron-rich terracotta. In her view, “a lot of crafts are endangered because there’s no patronage. The younger generation doesn’t want to learn from their parents. My dream is that they realise the worth of their crafts or we’ll lose everything. New ideas are important.”

Madhavi Gore from Goa is among artists eager to work with handloom artisans — descendants of those who built Vijayanagar: “I’ve worked on looms in a rudimentary way I’d like to finesse. For process-based art, you need space, and this” — she gestures at her studio — “provides it.”

But what of potential tensions between heavy industry and environmentalist art? “The energy needs we have are immense,” says Sharbendu De, a resident whose photography has chronicled the Delhi smog. “Cutting carbon will hit common people. So we have to find a more subtle and balanced way.” If steelmaking’s resources are coupled with robust artistic freedom, Hampi Art Labs might help open a path.

‘Right Foot First’ to May 31. hampiartlabs.com