While our study focused on a human case of swine influenza, it quickly became clear that the surveillance systems in place prior to the event were important. Surveillance systems have multiple goals. For influenza in Canada, surveillance aims to detect and monitor the viruses, and to inform vaccines and policies [18, 19].

Routine communication structures

We describe below the usual communication channels in the swine sector, the human health sector, and across these two sectors.

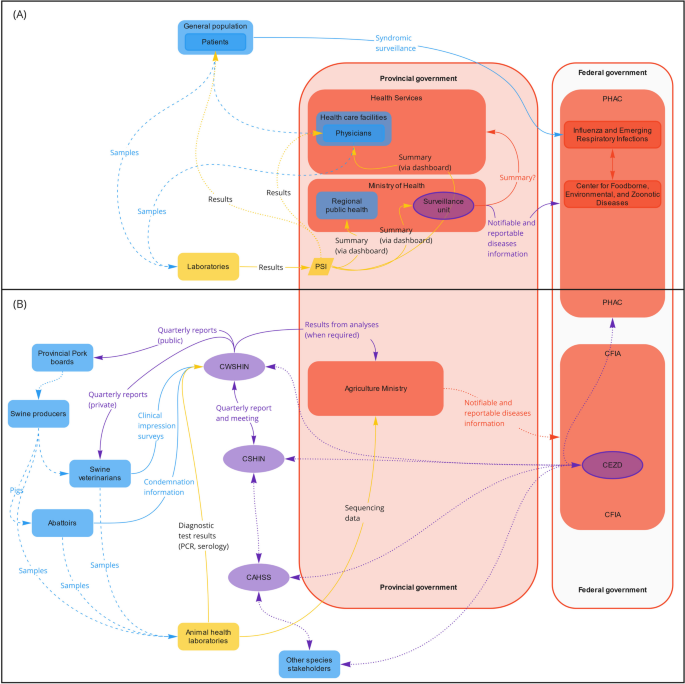

Routine communication channels for the surveillance of influenza virus infection in the swine sector in Alberta

Figure 1B shows communication channels as they flow (from left to right) in Alberta. Influenza virus in pigs is provincially notifiableFootnote 2 in Alberta, British Columbia and Saskatchewan, but it is not federally notifiable. At the regional level, the Canada West Swine Health Intelligence Network (CWSHIN) combines and analyzes the data from British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. It includes clinical impression surveys from swine veterinarians, laboratory diagnostic data from provincial and university laboratories (presence of pathogens, or serological or anatomical indicators), and condemnation rates from federally inspected slaughterhouses [11]. Once analyzed, the information is shared quarterly with veterinarians (reports, as private communications) and producers (reports, as public communications) and, when requested to address animal, human, or ecosystem concerns, with provincial governments (Fig. 1B). While some analyzed data are publicly available via reports for producers, our participants stated that there are no other direct communication channels between the CWSHIN and public health stakeholders. However, the regional surveillance networks (CWSHIN, Ontario Animal Health Network, and Réseau d’alerte et d’information zoosanitaire) are part of the Canadian Swine Health Intelligence Network (CSHIN) and the CAHSS, which include members from the National and Provincial pork councils, veterinary colleges, diagnostic laboratories, provincial governments, CFIA, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), and national and regional veterinary organizations and networks.

Structural communication links identified for human (A) and swine (B) influenza surveillance in Alberta. Information is usually shared from left to right: from laboratories, through the Provincial Surveillance Initiative system, back to the patients and referring physicians, as well as surveillance groups within the provincial government. Some information (anonymized) also flows to the federal government: from veterinarians, laboratories, and abattoirs to Swine Health Intelligence Networks (e.g., CWSHIN and CSHIN) to governments (provincial and federal). There is also publicly available information shared by the Community for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases to various stakeholders (from right to left). Dashed lines: samples; Full lines: data; Dotted lines: results/summaries. Blue: field stakeholders; Yellow: laboratories; Purple: intelligence; Red: government. CAHSS Canadian Animal Health Surveillance System; CEZD Community for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases; CFIA Canadian Food Inspection Agency; CSHIN Canadian Swine Health Intelligence Network; CWSHIN Canada West Swine Health Intelligence Network; GPHIN Global Public Health Intelligence Network; PHAC Public Health Agency of Canada; PSI Provincial Surveillance Initiative

Routine communication channels for the surveillance of influenza virus infection in the human sector in Alberta

In Alberta, laboratory data flow through a single laboratory information system (Provincial Surveillance Initiative; PSI), and information is automatically transmitted to stakeholders (e.g., physicians, patients, and surveillance units within the Ministry of Health; Fig. 1A) via an online platform. This system allows the linkage of clinical and epidemiological data with laboratory data at the provincial level.

The data about influenza collected by the healthcare system are gathered provincially and then anonymized and shared with FluWatch, a national surveillance program for influenza and influenza-like illnesses (ILI) [18]. The program monitors, inter alia, health care admission for influenza or ILI, laboratory-confirmed detection, syndromic surveillance, outbreak and severe outcome surveillance, and vaccine coverage; it shares weekly reports online [18]. At the provincial and federal levels, we were unable to identify other communication channels for providing human influenza surveillance information to animal health stakeholders.

Routine communication channels between the swine and human sectors for the surveillance of influenza in Alberta

Many swine health surveillance stakeholders are members of the Community for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases (CEZD). This multidisciplinary network of public and animal health experts from government, industry and academia was developed to support early warning, preparedness, and response for animal emerging and zoonotic diseases [20]. Open source signals are extracted automatically via the Knowledge Integration using Web Based Intelligence (KIWI) [21] and manually by the CEZD core team (CFIA employees). This team assesses signals daily, with rolling support from volunteer members and from expert partners from federal and provincial governments, academia, and industry when needed. Signals are then shared with the CEZD community, including through immediate notifications of important disease events, group notifications and pings, quarterly sector-specific intelligence reports and weekly intelligence reports.

Although CEZD was growing during the 2020-2021 period [22], membership is voluntary, as it is the case for CAHSS. Moreover, both networks cover multiple species and diseases, which serves to maximize the reach of the communities but can result in an overwhelming amount of information for members whose main interest is in another sector, such as human or ecosystem health. This large amount of information primarily relevant to other sectors can lead members to leave or not join these two networks.

Communication channels between sectors during a human case of swine influenza in Alberta

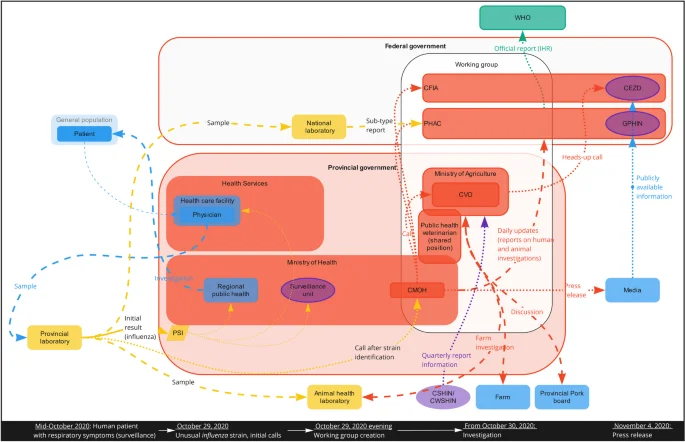

In all cases where a new influenza subtype, including an animal influenza subtype, is identified from a human case, this must be reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) under the IHR [23]. In Canada, PHAC is the body responsible for notifying the WHO of such cases. We examined the IHR-reportable case of a human infected with an animal influenza subtype identified in October 2020 in Alberta. The event we examined happened during an exceptional period for ILI as it was less than a year after the WHO declared the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) a global pandemic. At that time, influenza activity remained below average, most ILI symptoms were due to COVID-19 cases, and most public health and human health resources were dedicated to managing the pandemic [24].

In the case we investigated, the influenza subtype identified through sequencing performed at a provincial laboratory on October 29, 2020 (Fig. 2) in the human case was a variant similar to a swine influenza virus (A H1N2v). Samples from the human case were then sent to a reference laboratory, the National Laboratory of Microbiology (NLM) of PHAC, for confirmation. A provincial laboratory stakeholder also contacted a University Animal Health Laboratory colleague and sent the human sample in parallel for sequencing and confirmation that the variant was a swine virus.

Timeline and communication links during the human influenza A H1N2v case in Alberta. Dashed lines: samples; Full lines: data; Dotted lines: results/summaries Blue: field stakeholders; Yellow: laboratories; Green: intelligence; Red: government, Purple: international. CEZD Community for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases; CFIA Canadian Food Inspection Agency; CMOH Chief Medical Officer of Health; CSHIN Canadian Swine Health Intelligence Network; CVO Chief Veterinary Officer; CWSHIN Canada West Swine Health Intelligence Network; GPHIN Global Public Health Intelligence Network; PHAC Public Health Agency of Canada; PSI Provincial Surveillance Initiative; WHO World Health Organization

Because the human case was IHR reportable and had potential for high visibility, the provincial laboratory immediately contacted the Alberta Chief Medical Officer of Health (CMOH). Provincial and federal government stakeholders (Alberta Health, Alberta Health Services, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, PHAC, CFIA) were called to an evening meeting to raise awareness and ensure that the situation was managed in a way that satisfied provincial, federal and international obligations. This “H1N2v working group” was put in place quickly, apparently following the initiative of the Alberta CMOH (not confirmed as no interview was conducted with the initiators of this working group).

The information PHAC received through formal communication channels (e.g., from the NLM) took longer compared to the original call by the CMOH and the H1N2v working group. For this study, we did not have access to the guidelines in place for such an event, and it is unclear if the other stakeholders (provincial Ministry of Agriculture and CFIA) were officially needed to be involved.

Because swine influenza is endemic in the porcine population and this case was of importance for human health, the provincial public health stakeholders led the initiative, with the support of other stakeholders. The H1N2v working group met at least twice following the initial meeting. Additionally, follow-up data was gathered at the provincial level via multiple channels (public health, animal health, epidemiological, and laboratory investigations), and findings from the various investigations were shared with PHAC daily for a week and then weekly for two additional weeks. Information sharing between provincial and federal public health entities seemed to follow a formal process, but while we had access to the communication template, none of the interviewed participants had information about the structure supporting this initiative.

In the meantime, regional public health partners (within Alberta Health Services) were mandated to conduct the field investigation for the human case and its contacts with humans and pigs, supported by Alberta Agriculture and Forestry and stakeholders from the swine sector (e.g., Alberta Pork). The investigation’s goal was to clarify whether the infection was contracted from animal-to-person (directly or indirectly) or person-to-person. The public health investigation, the available information about swine influenza in the province (obtained from the CSHIN report), and the farm investigation performed in collaboration with an Animal Health Laboratory all provided supporting data.

The human and animal investigation data were collected by multiple stakeholders. The communication of results followed formal structures through Alberta Health (case, laboratory and epidemiological investigation results) and Alberta Agriculture and Forestry (farm investigation results) and were ultimately shared with PHAC. Interviewees reported that coordination of the two provincial ministries in this case was facilitated by the public health veterinarian, whose position is shared between the two ministries. Interviewees also said that in the investigation’s early stages, the swine sector’s participation in the farm investigation (an informal channel, via Alberta Pork) facilitated communication between the government and the farm involved. This highlights the importance of strong formal and informal government-industry relationships, which ensured that farmers and stakeholders trusted the system enough to support the investigation.

While the investigation was still ongoing and a clearer picture of the case and its transmission was emerging, a decision was made to make the information public. Our interviews did not identify the process leading to this decision, but six days after the initial notification to the government officials, an Alberta CMOH press release was distributed, with information stating there was limited risk for the general population. This now-public information was then identified by at least two Canadian event-based surveillance (EBS) systems that distributed the information to their communities. One of the EBS interviewees mentioned, however, that they received an email from the Alberta Agriculture and Forestry the night before the press release so they could prepare for it and have a notification ready to be shared. This informal communication channel seemed to arise from a preexisting relationship between stakeholders involved.

Encouraging and inhibiting elements involved in OH communication

The communication channels evident in our case study allowed us to identify elements involved in the information flow between animal and human health stakeholders (Table 3). Identifying what information needed to be shared between sectors was influenced by actors’ understanding of the evidence needed to trigger decisions and actions. During the surveillance phase, information was available online from the animal health (CWSHIN, CSHIN, CAHSS, CEZD) and human health (FluWatch, Global Public Health Intelligence Network) sectors. However, it was difficult to quantify how much these sources were used by different stakeholders. We identified little other communication between animal and human health stakeholders during this phase. Stakeholders reported having very limited time and resources to consult and use information from other sectors, suggesting a need for policies and structural integration of OH. For example, having a public health veterinarian appointed at both the provincial agriculture and health ministries was mentioned as a key element facilitating communication and coordination (Quote 1).

Quote 1.

“When the pandemic started, we had our public health veterinarian position empty. […] That position is essentially fully dedicated to working between the two ministries [Agriculture and Health]. It [the impact of this vacancy] showed itself in terms of just some gaps for them working on things without consulting us, but then [when] that position was filled and the other relationships were in place, everything just went really smoothly. […] it demonstrated the importance of those relationships and… having a good liaison between the two departments.”

During the outbreak, surveillance, laboratory, and industry information on swine influenza was quickly available to human health stakeholders. Animal health stakeholders, however, noted that the communication was, unfortunately and as in many cases, only one way. Barriers to within- and cross-sector communication included complicated or lacking communication channels. In our case study, there was a formal channel between the provincial and federal government due to the IHR requirements, but this is not the case for non-IHR-reportable zoonotic diseases. Moreover, the CMOH’s phone call to other stakeholders to create the H1N2v working group occurred faster than the formal communication channels.

Established professional connections facilitated information flow between stakeholders who understood each other’s needs and interests. While a lack of formal channels was identified as a pitfall due to potentially missed communication opportunities, many participants mentioned that established, informal relationships and networks facilitated information sharing – both the assessment of how much and what type of information to share and with whom it should be shared. Informal and formal communication channels were also affected by privacy and ethical concerns. Raw data, usually confidential, obtained from either the animal or human health sectors cannot easily be shared, adding to the complexity of formal communication channels. Analyzed or summarized data (i.e., information) were easier for both animal and human health sectors to share in reports or online platforms.

Trust, which can be defined as the perceived benevolence, integrity, competence and predictability of the other [25], was identified as the foundation for good communication among different stakeholders, whether via formal or informal channels. Here, previous interactions between stakeholders likely served as a basis for trusting that the person receiving the information would be kind, competent, honest, and predictable when using it. From the perspective of animal health stakeholders, however, trust was more difficult: the perceived anthropocentric perspective of health initiatives, including OH initiatives [26], created fear that shared information might not be reciprocated and would have negative repercussions on animals and producers (Quote 2).

Quote 2.

“You need to build trust and it takes a long time […] you need to build that trust with individual livestock sectors, that human health is not going to destroy the sectora. The [animal health] sector is generally very cautious because their perspective is very rarely considered […] if you have a human pathogen […] in livestock and it can potentially transfer to people, all the burden is very often on the livestock. […] Human health has a lot of resources and animal health doesn’t, but they get all [the burden]. It’s a matter of who [has] the cost and who’s benefiting.”

aWhile the stakeholder interviewed did not give additional details, they could have been referring to the case of a herd where an emerging influenza virus (H1N1v) was identified, which resulted in depopulation of the herd [4]. This was a severe consequence for the farmer, while the source of the virus was determined to be an infected human. They could also have been referring to the possibility of zoonotic events decreasing the marketability of meat because of public perception or export restrictions. This was unfortunately not discussed further in the interview

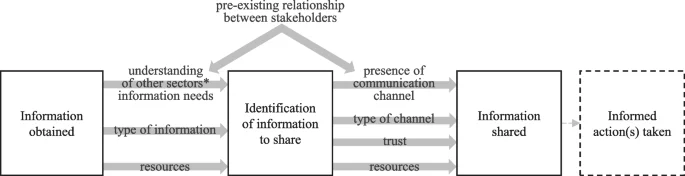

Interviewees suggested that information sharing requires two main steps: (1) identifying what information must be shared and (2) sharing that information with another sector (Fig. 3). Once stakeholders within a sector had information, the first step was identifying what should and can be shared, with whom, and through what channels. This could be facilitated or impeded by actors’ perceptions of other sectors’ needs, the type of information that is available, and the resources available. For sharing information itself, both the presence and type of communication channels were critical for external information sharing with other sectors – but so were trust and the availability of resources. Preexisting relationships among stakeholders also shaped actors’ understanding of each other’s needs, the presence of informal channels, and trust.

Elements linking the steps involved between obtaining information and sharing information to another health sector

*The two sectors examined in the present case study are animal health and human health