Climate connectivity explained: What is it and how can you support it?

By Chloe Bennett

Warmer temperatures are triggering more extreme weather in the park, including heavier rain and shorter winters. Researchers aren’t certain how local flora and fauna will change with developments, but studies suggest they could be on the move.

Nearly half of the world’s species may be moving northward and upslope, studies show. Fostering pathways and land connections could be key to helping some species survive the effects of climate change.

What is climate connectivity?

Plants and animals in the coming decades may need to travel long distances to find suitable climates and habitat. A 2016 research paper coined climate connectivity using established science and maps of wild areas in the U.S.

Jenny McGuire, an author of the study, said many animals are tracking to cooler areas, but much of the country’s wilderness is cut by development and roads. Planning for the migration is key to climate connectivity, the research shows.

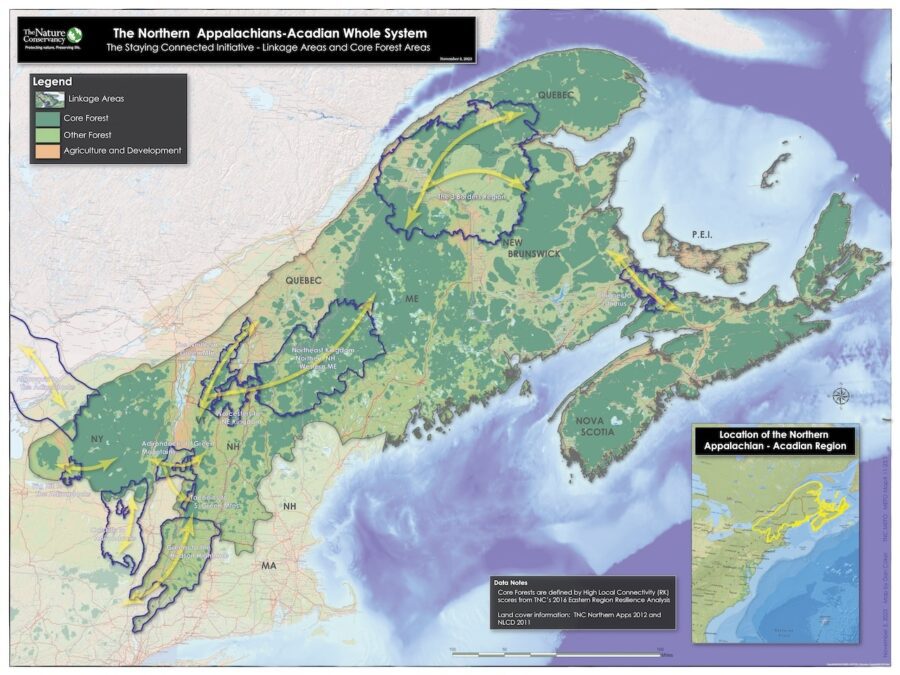

Wildlife corridors, which are designed to aid animals along undeveloped land and waters, are prioritized by conservationists looking to boost connectivity. The North Country is close to several of the linkages, including Tug Hill to the west, Algonquin in Canada and Vermont’s Green Mountains.

How are the Adirondacks involved?

The Adirondacks are a nexus to the network of corridors and could provide critical habitat for species on the move. Its location and heavily forested land would benefit the migrating species, scientists say.

The protected park could also one day provide a breeding ground for declining animal populations, said Alissa Fadden, wildlife connectivity project manager for The Nature Conservancy. The organization views the Adirondacks as a stronghold against extreme weather that is expected to increase with climate change.

John Davis, a rewilding advocate based in the Champlain Valley, said the wilder the land, the better suited it is for the effects of climate change.

“Big wild connected habitats will tend to be more resilient, they’ll tend to withstand disturbances, natural and unnatural, more successfully than will fragmented habitats,”

JOhn Davis, who created the Hemlock Rock Wildlife Sanctuary on his land in Westport.

Are unusual animals going to appear in my backyard?

Plants and animals with permanent homes in southern climes will not show up in the Adirondacks tomorrow, as climate migration could take decades or centuries. Some efforts to move species proactively as temperatures rise have been made, such as assisted migration for monarchs in Mexico, but no such large-scale efforts are currently underway in the park.

How can I support animal migration and climate connectivity?

Adirondackers who want to conserve their land can work with local organizations to ensure connectivity. Fadden suggests strategies including keeping lands completely wild or managing forests for wildlife and climate resilience. That can be done through individual experts or by entering a conservation easement with the state.

“We also often would suggest meeting with a consultant or someone who maybe has experience in managing habitat for specific wildlife species that they’re interested in or increased resiliency so that their properties are well positioned to better withstand the impacts of climate change,” Fadden said.

People with plots big and small are encouraged to reach out to the conservancy, the connectivity project planner said. Small properties can add up to a large linkage of wild land to support migrating species.

“All of these things really play a role in keeping our landscapes healthy and connected, these are all solutions to the big issues that we’re facing,” Fadden said.

Photo at the top by Jeff Nadler

<!–

–>