Revisiting a theory about chance collisions and innovation.

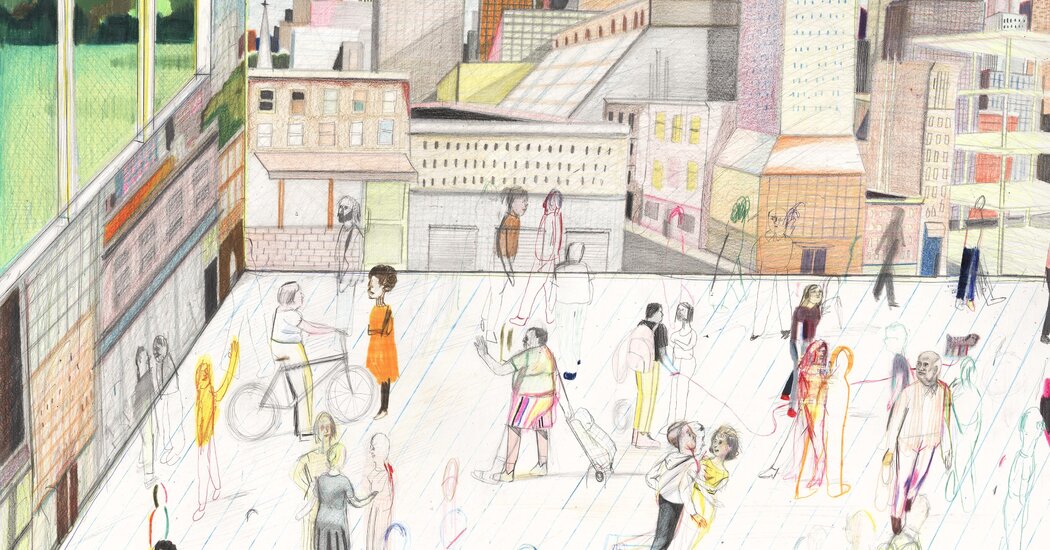

There is a thing that happens in cities — that we think happens in cities — when people with lots of different ideas bump into each other on the sidewalk, or at the bar or the grocery store or the gym. Together, they think up things that would never come out of a conference room or the kind of coffee meeting that has a calendar invite. Weird new ideas take root. Innovation follows.

The urbanist icon Jane Jacobs identified these collisions as central to what makes cities dynamic. Her followers think of them as the product of serendipity. Economists have their own name for the almost-magical benefit these connections create: knowledge spillovers. “The chance encounters facilitated by cities,” the economist Edward Glaeser has written, “are the stuff of human progress.”

Remote work has, well, blurred this picture. Can you have serendipity two days a week? Where do people bump into one another when the downtown coffee shops are closed? How do workers spill their knowledge when they’ve moved to Montana, or the exurbs? Does that even matter anymore?

“It’s a trying time, certainly, for my view of the world,” said Enrico Moretti, a Berkeley economist who has written extensively about why it’s good for workers, companies and the economy when people cluster in particular cities.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

We are confirming your access to this article, this will take just a moment. However, if you are using Reader mode please log in, subscribe, or exit Reader mode since we are unable to verify access in that state.

Confirming article access.

If you are a subscriber, please log in.