I left New York in 2009 for grad school, and by the time I returned—just a few years later—the city had been transformed. Walking to the subway, on the sidewalks and escalators, almost everyone carried a pet screen. Sometimes people banged into things or ran into each other, too absorbed in the digital world to navigate the real one. Commuters swooned over their devices on the train, heads drooping and backs bent, like so many nodding-off drunks. It happened to me too. My phone started to exert a strange power over me—the nagging urge to check and check again. In every awkward or in-between moment, I wanted to look at the dazzling light.

The change felt rapid, jarring, otherworldly, like something in a movie. And yet I couldn’t shake the feeling that it was even bigger than we knew. In our rush to embrace the smartphone we were making a profound, maybe irreversible choice based on limited information, with implications we could only dimly glimpse. Was that a good idea? This wasn’t a question that anyone—individually, collectively—seemed to give much thought. It had already been decided, somehow. The assumption was always that we’d all consent.

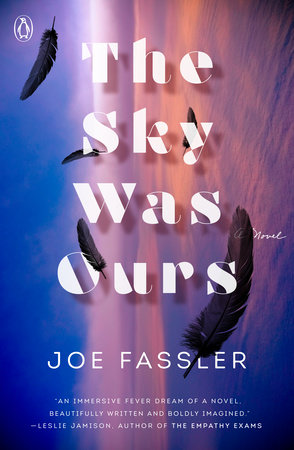

By then, I was working in earnest on my novel, The Sky Was Ours, which is about a very different technology: a huge pair of wings, made from simple materials and designed to fit the human body. If a few engineering problems can only be worked out, my characters believe, people will finally fly like birds, traveling freely across the climate-ravaged earth. I wanted to feature a manmade innovation almost like a central character, the way the iPhone has become a character in all our stories. And I wanted to examine the psychological appeal of disruptive tech—our deep-down desire to see everything change, even if that means unleashing forces beyond our control.

As I wrote, I started to seek out other novels and stories that open up what Stephen King once called “Pandora’s technobox”—that explore the unintended consequences of the radically new. In these books, all set in warped versions of today’s reality, fictional contrivances play a key role in the drama. Each one, in its way, is alive to a central paradox of our moment. Yes, powerful technologies can expand the scope of what’s possible, but they also invent new forms of loss.

Galatea 2.2 by Richard Powers

This novel, by far the oldest book on this list, came out in 1995. But its plot could have been ripped from this week’s headlines. The narrator, a mid-career novelist also named Richard Powers, is up late in his campus office when he hears strains of Mozart echoing down the hall, the same passage played again and again. He investigates, and discovers a colleague looping the sonata for his computer system—an early attempt to train a neural net. Powers steps into the teacher role, and over time a new character emerges: Helen, an artificially intelligent machine consciousness, at once eerily human and profoundly not. Their story pulls at knotty questions about machine authorship, human-AI relationships, and the origins of consciousness itself. An astonishing, prescient tale that reads with fresh urgency today.

Something New Under the Sun by Alexandra Kleeman

Kleeman’s immersive novel conjures an unsettling, near-future vision of Los Angeles. Smoke chokes the air, forest fires rage up in the hills, traffic clogs the 405, and yet the Hollywood hype machine churns on. The main characters just want make a movie, but our beleaguered planet has other plans: all across the southwest, after years of squandered resources and persistent drought, the water’s gone. Gone gone. For their very survival, Angelenos have started depending on a mysterious company called WAT-R Corp, which has learned to make synthetic H20 in a proprietary process. The new, cleaner, and tastier option supposedly beats the original across every metric. And though it’s also much more expensive — and may have other, well, unexpected issues — any drawbacks are kind of beside the point, since millions of thirst-crazed customers have no choice except to buy. This bracing book walks a knife’s edge between eco-horror and wildly funny satire, underscoring how desperately we need what nature offers freely. A blazing call to reclaim and save from ruin all we take for granted.

The Candy House by Jennifer Egan

In some ways, the invention at the heart of Egan’s novel isn’t so different from today’s internet: it’s a portal that lets billions of strangers connect. But our texts and posts and reels seem pretty crude compared to what’s possible with the Mandala Consciousness Cube, which lets you crawl fully inside another person’s skull. With the help of a few electrodes, people can upload their memories into a vast repository, where they can be viscerally experienced by anyone with a cube. (The device, as it works, becomes “warm as a freshly laid egg.”) It’s an unnerving portrait of the way technology hacks individual agency, coercing us into adoption no matter how much we might want to resist. And as the cube collapses distance between people, resulting in new connections that can be redemptive or uncomfortably close, Egan seems to wonder: Do we really need Silicon Valley to understand each other better? Don’t we already have fiction?

The Immortal King Rao by Vauhini Vara

On a near-future earth threatened by cataclysmic warming, a super-intelligent algorithm is tasked with handling every aspect of governance, settling political, legal, and individual questions with the final authority of a monarch-oracle. But King Rao, the Algo’s ruthlessly ambitious tech-billionaire creator, isn’t content to stop there. When his experiments with a Neuralink-like networked brain implant end in scandal, he retreats into exile with his child daughter, Athena—whose brain he’s modified with the device. This cognitive enhancement makes the book’s glorious narration possible; Athena tells the story in the heightened, virtuosic register of a fully networked mind. And yet her godlike father’s legacy, inescapable and burrowed physically into her very body, is its own kind of torment. A brilliant and subversive smash-up of established forms — the immigrant family saga, the Bildungsroman, the dystopian epic — King Rao takes aim at the techno-cultural guardrails that constrain human experience, and uplifts our desire to find new possibilities beyond them.

After World by Debbie Urbanski

After World is a kaleidoscopic book written from the perspective of an AI, a machine consciousness tasked with studying the last human being alive on earth. That human character, Sen, is the lone survivor of The Transition — a well-meaning apocalypse brought about by, well, AI — who is forced to record her feelings in a sequence of written reflections. Slowly, we start to understand what’s happened: tasked with saving the earth, the novel’s robot overlords concluded (not unreasonably) that human beings were the problem. So they annihilated humanity and prepared to rewild the planet. But as the natural world begins to heal from civilization’s ravages, we can’t help mourning what’s been lost in the process: us. (“Even if we ruined everything, I think we still deserve to live,” Sen writes in her journal. “Don’t we? Didn’t we?”) The result is a riveting portrayal of a post-human landscape, a moving elegy for our beautiful, flawed species.

Green Frog by Gina Chung

Green Frog’s electrifying, unnerving narratives mix the mundane with more fantastical forms, often in the confessional first-person. One story anthropomorphizes a female praying mantis, recasting its murderous mating ritual as a romantic evening gone awry. There’s a recipe for cooking and eating one’s own heart. A centerpiece is “Presence,” a long story that features a memory-externalization device that takes the world by storm. Unlike Egan’s Mandala Cube, the Neolaia app allows users to disburden themselves, purging any “Adverse Life Experiences” forever. Take too many memories away, though, and you risk some serious side effects — as the narrator, a key scientist on the project, slowly begins to learn. A masterful portrayal of startup ethics run amok, “Presence” reckons with what’s lost when we can choose how much to feel.

Exhalation by Ted Chiang

Some of Chiang’s best stories chart the ways imagined scientific breakthroughs recast experience, for better and for worse. In this collection, a device predicts how you’ll behave before you do, raising terrifying questions about the nature of free will. A “lifelogging” device allows the wearer to recall every moment of one’s life (It also results in surprising forms of amnesia.) But “The Great Silence,” my favorite story in Exhalation, is about a real-life piece of technology: the Arecibo radio telescope. Before its unexpected collapse in 2020, the Arecibo had been used to beam messages into outer space, and listen for them, too — part of our ongoing search for extraterrestrial life. This obsession affronts the story’s narrator, a talking parrot. If humans want to commune with intelligent life so badly, he suggests, they might look a little closer to home. What invention would give us ears to hear the planet’s living creatures as they rapidly fall silent, as species after species succumbs to extinction? What would it take for us to tune into a different voice: the cry of the animal world, begging our kind for mercy?