As a child, Selina Brown had a Saturday routine: her mother would go shopping and leave her at the library, where she would speed her way through novels by Jacqueline Wilson and RL Stine’s Goosebumps series. Yet, as a Black girl, she rarely saw herself represented in the books on the library’s shelves.

Years later, she self-published a children’s book, Nena: The Green Juice. “I did encounter some problems,” she says. “I thought it was me alone. I spoke to other Black authors and realised there was an issue.” That became the seed for the Black British book festival, which is now in its third year.

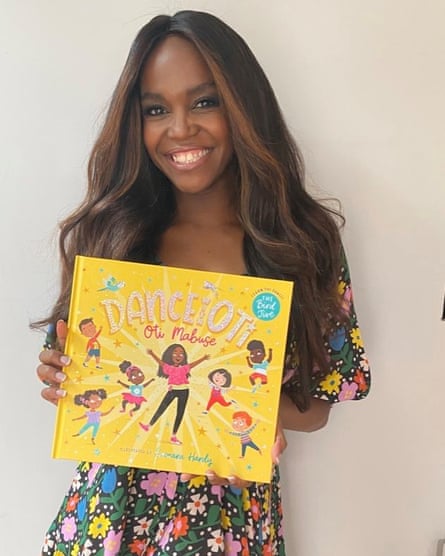

The festival, taking place on 27 and 28 October in London, will be opened by Little Mix singer Leigh-Anne Pinnock, whose memoir, Believe, is coming out this month. Oti Mabuse, the South African dancer who has twice won Strictly and has written several children’s books, will also appear. The lineup reflects a broader move by literary festivals recently to include more speakers from the world of entertainment: this year’s Hay festival – a partner of the Black British book festival – also had starry headliners, including Dua Lipa, who runs a book club, and Stormzy, who is behind the publishing imprint #MerkyBooks.

The Black British book festival will also feature appearances from children’s laureate Joseph Coelho, journalist and writer Gary Younge and Dawn Butler MP among others. When selecting speakers, Brown says she was looking to facilitate “conversations that will move people, that will spark joy within people, that will spark knowledge within people, that will change the audience in some way”.

The central aim of the festival is to celebrate Black British authors, including emerging ones. “There were lots of conversations during 2020 especially with the hashtag #PublishingPaidMe which highlighted the disparities in how Black authors are treated within the publishing industry,” says Kelechi Okafor, whose short story collection, Edge of Here, was published in September. In 2021, analysis by the Guardian revealed that Black authors made up just 6% of shortlists for the UK’s top literary prizes in the previous 25 years. Over the same period, Black Britons made up only 3.1% of shortlisted writers.

“We’re a political festival that’s trying to make a shift,” says Brown. “It’s driven by more than just having a good time and having a nice festival.” Eric Collins, author of We Don’t Need Permission, sees the festival as the “tip of the wedge” in creating “more dynamism in the marketplace” for Black literature.

The festival was previously held in Birmingham, but has now moved to London’s Southbank Centre. It will feature a masterclass zone – which will host a panel discussion between Younge, Butler, broadcaster and writer Clive Myrie and author Kehinde Andrews – a children’s zone, an ideas zone and a workshop zone, with sessions on securing a literary agent and writing engaging dialogue.

Younge, author of several books including Dispatches from the Diaspora, says that a festival like this “brings together a group of people who would otherwise not necessarily find themselves in the same room and who probably should, from time to time”.

Collins adds that “if you are reading Black literature”, you can then be “within the gaze of other people like you, within the community of people like you, communing around these documents that have been feeding and nourishing your soul, and to see the other people who are being fed and nourished along with you”.

Younge says that a festival focused on Black literature “can be an issue for some”. People ask things like: “What if I had a white British festival?”

after newsletter promotion

“Well, for years they were white – they were called Cheltenham, Edinburgh and so on,” he says. Indeed, a 2015 report found that of the more than 2,000 names appearing at Edinburgh, Cheltenham and Hay in the previous year, just 100 – 4% – were Black Caribbean, Black African, south Asian or east Asian, and UK-based. “Lots of festivals are still very white,” Younge says.

While the festival’s events focus on Black experiences, it is open to everybody, Brown says. “We want everyone to experience culture because that’s how we make shifts and that’s how we learn from each other”.

Another aim of the festival is to promote reading for pleasure in marginalised communities. “Knowledge is power, really,” says Mabuse. “And the more knowledge people have the more powerful they’ll feel.”

Okafor recalls reading Mills & Boon novels when she was younger and having to seek out writers such as Malorie Blackman and Dorothy Koomson herself. “Finding my way to Black authors on my own, essentially. That’s why it’s important to introduce people or to remind people of the talent that’s out there,” she says.

“I grew up knowing more about Black American literature than I ever did about Black British literature,” says Younge. “Now we’re in a different place in terms of the number of people who have been published, their promotion and the notion that Black British books can sell,” he adds. “There is value in seeing this category as a viable dynamic category.”