For as long as we can remember (and excuse this lofty introduction), genre has served the dual purpose of business and pleasure. When you hear sci-fi, you often think of laser guns, riotous botanical monsters, or even the slowly scrolling words that begin “A long time ago in a galaxy far far away.” But consider too the specific ways genre addresses larger questions at hand, like how The Left Hand of Darkness, The Yellow Wallpaper, or the Tensorate series tackle sex and gender. We read horror, fantasy, and more to make sense of things, to recontextualize current issues in different settings, or to dive into the nitty gritty of what makes us really human. But I especially love when genre is used to expose the intimate matters carved into our hearts.

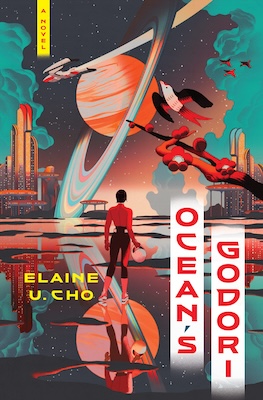

Ocean’s Godori, my debut novel, is a space opera with hoverbike chases, high stakes space races, and a found family of misfits thrust into interplanetary conflict. But at its core, it’s really about a group of people navigating their messy 20s. In particular, the three main characters–Ocean, Teo, and Haven–wrestle with what it means to forge a future while still honoring where and who they come from. Ocean has been rejected from her mother’s group of haenyeo, Jeju Island’s beloved female divers, and has long struggled with feeling Korean. Teo’s always been the black sheep as the second son of the extremely polished Anand Tech empire. And then we have Haven, whose work is in preserving the death cultures and rituals of the past, while he navigates a complex present relationship with his parents.

The following eight titles also feature characters in contention with generations before or after, in stories that somehow use genre to explore those conflicts. There are girls with tiger tails, spaceships, and diaspora blues. But even as our heroes or anti-heroes face fantastical monsters and far-off places, they often find that the knottiest problems arise from their own families. And as we read, perhaps we’ll discover that these deep-space experiences aren’t so foreign after all, and that maybe we can get a better understanding of those questions we’ve kept close to ourselves.

How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe by Charles Yu

Charles Yu brings us into what at first appears to be a sci-fi jaunt full of hijinks. The protagonist, Charles Yu (yes, same as the author) is a time machine mechanic and you think you’re having a jolly time with a down-on-his-luck worker who has a depressed computer sidekick and whose job is preventing grandfather paradoxes. And then Yu (the author, not the character) punches you in the gut with the realization that you’re reading a treatise on his search through time for a (physically and emotionally) lost father, and the absolute heartbreak of watching his mother stuck in her own nostalgic time loop. It’s hilarious and witty, it’s clever and smart, and it’s completely heart-wrenching.

Throwback by Maurene Goo

Here’s another time travel book about generational conflict, but how about if we bring a first-generation Asian American immigrant and her daughter to a level playing field? After a blowout fight with her mom, high schooler Sam downloads a mysterious rideshare app that ends up… taking her to another decade?? Now Sam’s trying to survive in the 90s and she has to deal with the retro culture, the regressive racism, and maybe worst of all… her teenage mom who’s fighting to win the prom queen crown. Goo hits that sweet spot of those fun Back to the Future vibes combined with Sam’s tender coming-of-age. She adroitly uses the time travel mechanism in this generous and nuanced intergenerational portrayal.

The Only Good Indians by Stephen Graham Jones

Stephen Graham Jones brilliantly delves into and excavates themes of generational trauma and cultural identity in his writing, and many of his books would fit the list, but I simply cannot ever pass up an opportunity to recommend The Only Good Indians. Four friends, American Indian men, find their past deeds returning to haunt them one by one in visceral, vengeful ways. How does one escape the past? Is it possible to forge your own identity while acknowledging the culture that has shaped you? And are our future generations forced to bear the burdens of our failures? Jones answers these questions with blood, horror, and, yes, even basketball.

The Magical Language of Others by E.J. Koh

Yes, this is Koh’s memoir and you might say But Elaine, how is it genre, and I’ll tell you: It’s an epistolary memoir, but truth be told I really just need everyone to read E.J. Koh. The Magical Language of Others is the coming-of-age memoir of poet and translator Koh, but her gorgeous writing is structured by her translation of letters that her mother wrote to her in Korean. These letters intersperse the intergenerational story of Koh, her mother, and her grandmothers. Her mother writes simplistic letters because they were meant for a young Koh, but Koh also bridges the gap in her translation by striving to understand her mother’s true intent (as all the best translators do). The letters come without commentary, and there’s a compassion and generosity to this presentation, as it allows us to read and come to understand them in our own way as well as through the lens of Koh’s life. Even more than Koh’s lovely words, the letters illustrate the multitude of ways she and her mother reach out to each other.

Bestiary by K-Ming Chang

Another book where translated letters play a crucial element, Bestiary is a novel about three generations of Taiwanese American women: Grandmother, Mother, Daughter. Naming them so emphasizes the fable-like quality of Bestiary but also, of course, the thematic focus on generations. Bestiary is an apt description of Chang’s prose, which bursts to life with vibrant, variegated, and fierce language. Daughter digs out Grandmother’s letters from holes in her family’s yard, and painstakingly translates them. She wrestles with the ghosts of grief and trauma, with the beasts mythical and very real of her family’s past. And while her body grows in yearning and undergoes its own fantastical changes, it carries forth the myths and traumas of Mother and Grandmother before her.

The Deep Sky by Yume Kitasei

Eighty elite graduates of a competitive Earth program have been selected as humanity’s last hope to travel to a far-off, habitable planet. But while on board the spaceship, a bomb explodes, jeopardizing the mission, and throwing the remaining crew members into suspicion. The sci-fi genre sets the stage for a space thriller whodunnit, but through it, Kitasei also probes our deepest desires to belong even when we’ve convinced ourselves we don’t deserve to. The Deep Sky flashes back and forth in time, between the mystery unfolding on the ship and half-Japanese Asuka’s time back on Earth as she struggles with her mother, her self-worth, and her role as the Japanese representative of humanity’s future. As it does so, it weaves a similar narrative in how entangled our pasts and futures are.

Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez, translated by Megan McDowell

Our Share of Night starts as a strange road trip between father and son, but are they running away from something or to it? You could probably chalk a lot of the off-kilter eeriness to the father and son’s shared grief at recently losing wife and mother, Rosario. That is, until the young son, Gaspar, asks about the strange woman standing in their hotel room. Enriquez uses the horror genre to explore the very real brutality of the military dictatorship and its aftermath in 1960s Argentina, but also the intense relationship of Gaspar and his father, Juan, who has been trying to break free of a demonic cult. Juan desperately wants to protect his son from its clutches even as he realizes that it’s his blood that endangers the child. Gaspar and Juan fight each other, sometimes physically, and sometimes inflicting trauma through supernatural means, but it’s a tumultuous relationship that’s also undeniably bound in their tenderness for each other. The cult wants to kill Gasper to force Juan to achieve immortality by living through his son’s body, but what is that but an analogy for the ways families fight to live on through their progeny?

Same Bed Different Dreams by Ed Park

Sometimes it seems difficult to talk about Same Bed Different Dreams because it’s so many things, but then again it allows me to sneak it into every single conversation, recommendation, and list. Ed Park’s Same Bed Different Dreams is a tripartite story, a blend of non-fiction and fiction, a heady entwining of Korean history both real and imagined. It’s appropriate then, that it opens with the question “What is history?” While initially presented as a sort of kicker to a think tank, Park uses his words to directly ask that of us the readers. And as Same Bed traverses its puzzle box of a story, it jumps genres and moves forward, backward, and sideways between fathers and daughters to reveal how our histories and stories are sought out, challenged, and carried forward by the generations that follow. What is our part in creating those stories and preserving those histories? It’s perhaps the best answer to Min Jin Lee’s own famous opener: “History has failed us, but no matter.”