“He looks different, and he acts different,” commented YouTuber user ichuze7312 under a video of Kanye West and new wife Bianca Censori being followed around by paparazzi while out buying ice cream in Los Angeles. “I don’t think this is Kanye.”

Another thread on Reddit expressed concern that the out-of-shape Kanye currently wandering across Milan without shoes wasn’t simply the result of ageing, or even some misjudged artistic statement about Jesus humbly walking through the streets barefoot, but rather evidence that the troubled rapper is now a different person altogether.

Ridiculous as it sounds, the idea that some of our most famous celebrities have been replaced by mentally neutered clones is something that has soared across the internet over recent years, evolving into the kind of conspiracy theory that is openly discussed (in playgrounds, at least – my 10-year-old nephew recently revealed how everyone at school believes Eminem was cloned).

In August Oscar-winning actor Jamie Foxx put out a video statement addressing rumours (including the idea he had been cloned), when his thinner appearance – following a battle with a serious illness – raised alarm and became catnip for TikTok truthers. “I went to hell and back, and my road to recovery has some potholes as well, but I’m coming back,” Foxx said.

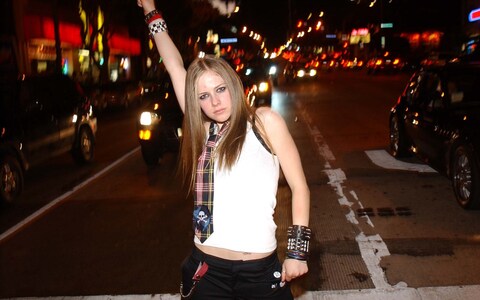

Meanwhile, the likes of Gucci Mane, Marshall Mathers – aka Eminem –, Zac Efron, Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, and Avril Lavigne have all previously been accused of being replaced by clones in popular social media posts. Lavigne, for example, is said to have died in a 2003 car crash and secretly swapped by label bosses with a body double called Melissa Vandella.

Avril Lavigne is believed to have been doubled by Melissa Vandella

Credit: Jeff Kravitz

The concept of some shadowy organisation replacing our most beloved actors and artists with doubles that can be more easily controlled, or even just wealthy celebrities deceptively preserving themselves through a top-secret human cloning program so that their death is less final, might all sound like the plot to a Black Mirror episode.

But whenever a celebrity disappears from the spotlight and returns looking different, human cloning provides an easy, fixed narrative for conspiracy theorists. In a world of fandoms and endless celebrity endorsement advertising, the famous have evolved to such a status that the public can also have difficulty in seeing them as human beings whose appearance can change over time.

“I wonder if the rise of human cloning conspiracies says something about the way these celebrities already seem like fantastical, supernatural beings, somehow capable of things that we are not,” ponders Philip Ball, science writer and author of Unnatural: the Heretical Ideal of Making People. “Some of the conspiracies draw on the silly idea that somehow you can take a full-grown adult and clone them to make an identical adult. There’s a strong echo in these stories of old narratives of doppelgängers, which have always held a fascination.”

Mahershala Ali in Swan Song

Credit: Apple TV

The roots of human cloning certainly go deep, with doppelgängers appearing in German folklore stories as a sort of evil twin and used for the first time in print with the novel Siebenkäs (1796) by Jean Paul. Writers in the 19th century including E.T.A. Hoffmann, Edgar Allen Poe, and Robert Louis Stevenson all followed with their own doppelgänger stories. In 20th century literature, this tradition continued with popular novels like Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro and The Boys from Brazil by Ira Levin. And, whether it’s The Island or The 6th Day, Hollywood has long experimented with human cloning stories, too.

In 2021, Apple’s sci-fi Swan Song showed a devoted yet terminally ill husband (Cameron, played by a stoic Mahershala Ali) choose to be replaced by a clone, saving his unaware family from the grief of his loss but also guaranteeing a lonely death. And in this year’s striking surrealist body horror Infinity Pool, director Brandon Cronenberg depicted a couple (played by Alexander Skarsgård and Cleopatra Coleman) on holiday at a Croatian resort where you can literally get away with killing.

There’s only one small caveat: you must agree to be cloned so your double can be executed for your crimes. This law results in giddy chaos, as a bunch of holidaying yuppies run wild and blow off steam via orgies, crimes, and murders, with an unhinged Mia Goth (who shouts things like “Stop being a baby!” at characters who refuse to slaughter children) acting as their unhinged cult leader.

Alexander Skarsgård in the film Infinity Pool

Credit: NEONTopic

So why is popular culture so obsessed right now with the idea of the world being overrun with clones? “I wonder if the fixation on doubling is partly driven by social media,” says Infinity Pool’s director Brandon Cronenberg. “It’s very common now to spend a great deal of time creating a fictional version for yourself for public consumption. You find people on the street literally recording multiple takes of their lives, and these idealized other selves are what they present to the world.”

It’s a fascinating social parallel. The director insists Infinity Pool, however, isn’t supposed to be a warning about the dangers of human cloning or how such a scientific development could be democratised by class, but rather an attempt to use the technology as an “absurdist” plot device. “The cloning in Infinity Pool is deliberately absurd,” the director reveals. “There is a dream logic to it, but not a real-world logic.”

At a time of global austerity, many of us wish we could live alternative lives. Therefore, the “magic” and “dream logic” of conspiracy theories around human cloning can offer a much-needed escapism. “I think that cloning, much like theories about parallel universes, allows us to explore fantasies about ‘lives that could have been’, including our own,” explains science writer Ball.

“You could say that this rise in conspiracy theories feeds into our inherent narcissism. Ultimately this becomes the loopy notion that cloning would be a form of immortality – as if our very consciousness or soul or whatever you want to call it would be transferred into a clone of ourselves. Cloning, like many new technologies, attracts plenty of magical thinking.”

But what about the conspiracy theorists themselves: what exactly is driving them to hold such zany beliefs? A member of the Facebook group, Stop Human Cloning 3, 45-year-old Matthew Hitchcock, who is from Austin, Texas, says his interest was piqued at a particularly difficult time in his life. “Since I was depressed, I found comfort in the excitement of exploring the unknown, and this left me in a vulnerable position to fall into endless conspiracy rabbit holes,” he says, “starting with human cloning.”

The reason the celebrity cloning conspiracies appealed so much to Hitchcock was because of their omnipresence in our pop culture. He continues: “I think it’s because Hollywood has made a lot of popular movies like Get Out, Us, and They Cloned Tyrone recently, and the idea of consciousness transfer, doppelgängers, and cloning has trickled down more into the thoughts of society, and onto social media platforms like TikTok where the varying theories can quickly reach a large number of people.

“Paul is Dead”: Beatles’ fans became convinced Paul McCarney was replaced by a double called William Shears

Credit: Central Press

“It’s a fun theory to discuss, and since scientists were cloning sheep in the 90s, it’s also somewhat plausible that the technology could have advanced since then and that the powers that be may not have the incentive to share it with us yet.”

He says that he no longer believes that Britney Spears was cloned (a belief he held previously), but says the reason there’s still such a high volume of believers online is due to radicalisation. “The groups definitely radicalise you since they act as a confirmation bias feedback loop. I viewed the other people in the group as the only credible sources I would accept and could be trusted since they were ‘in the know’.”

Another formative moment in the history of pop culture cloning is the “Paul is Dead” theory from 1966, when Beatles’ fans became convinced Paul McCarney had died in a car crash and been replaced by a double called William Shears. The real Paul had “died” when racing his Austin Healy home from a Sgt Peppers studio session and this idea spread like wildfire across college radio stations in America in the later part of the Swinging Sixties. Some fans claimed there were hidden messages confirming Paul’s death in Beatles songs that could only be heard when played backwards, while the fact he was barefoot on the cover of Abbey Road was cited as a hidden message about the real Paul being a corpse.

Picketing actors of SAG-AFTRA, and writers of the WGA, outside Netflix studios, July 21, 2023, in Los Angeles

Credit: Chris Pizzello

There’s also the fact that AI technology now makes it possible to clone 2Pac or Biggie’s voices to create “new” songs, which can be found all over streaming websites, such as YouTube. And the news that major label Universal is currently working with Google so they can create AI replications of deceased artists suggests a future where we’ll be immersed in digital clones, and potentially caught up in an exhausting state of perpetual nostalgia. The recent writer’s strike in America even raised concerns that studios might prioritise AI-based scripts, which will stop the need to pay human writers who can argue back and complain.

“Human beings have long been fascinated by stories about imposters who steal identities, partners, or assets,” says Kerry Lynn Macintosh, a lawyer professor at Santa Clara University and the author of 2013’s Human Cloning: Four Fallacies and Their Legal Consequences. “We particularly enjoy stories in which duplicates reveal a hidden, darker side of the self.”

Yet Macintosh is also keen to add: “However, in real life, human clones could never be convincing imposters or duplicates. They would be born as babies and grow up in different families and environments than their DNA donors, leading to differences in intelligence, physical appearance, personality, and values. It is not possible to copy a person.”

The United Nations General Assembly currently has a ban on human cloning, but the lawyer says this is “non-binding” and that research involving cloned human embryos is “ongoing in many countries”, with scientists believing this research can ultimately lead to cures for diseases. While this is a million miles away from a program used to re-create Hollywood actors, the fact this research is going on shows human cloning is much more than just a Philip K Dick fable.

Dolly, the first cloned sheep in Edinburgh, 1997

Credit: John Chadwick

But Ball believes that even though there’s no reason to think human reproductive cloning is “biologically impossible”, it’s unlikely to be something that becomes mainstream anytime soon. “At the moment, trying to create a person by cloning would be unethical as well as illegal, since we don’t know if there would be longer-term health risks,” the science writer adds. “There is no good argument that reproductive cloning is needed to cure disease. Of course, there is always the possibility that some maverick will try to do it.”

Rather cautiously, he continues: “We imagine film clichés like a copy of a person could be made from a stray hair left on a chair, or a residue on a wine glass. If a time comes when a person is brought into being by cloning, they will be just like anyone else. We need to challenge all the prejudices Hollywood has created about clones – that they are soulless and so on.”

Whether a fringe quack pioneers a new human cloning experiment and we get the human equivalent of Dolly the Sheep or not remains to be seen. Yet in a world where the idea of human cloning and deep fakes, Brandon Cronenberg believes conspiracy theories rooted in this subject matter will only continue to flourish. “Human cloning is compelling because it rejects scrutiny. What would it even mean for someone to be replaced by an exact double? How could you know, and what would it change?” he says.

Returning once again to his theory that social media obsession is a big driver of the current wave of human cloning conspiracy theories rippling through pop culture, Cronenberg concludes: “I suspect if you habitually create and maintain your own double, and this double is the version of you that is most visible, then the unreality of other people becomes almost assumed. In a sense, we are being replaced by doppelgängers of our own invention.”