CNN

—

The end of April is about to be the busiest week of Lauren Groff’s life.

In the span of a few days, the acclaimed author is set to share the stage at New York’s Lincoln Center with Margaret Atwood, where they’ll discuss their books about women in quiet fury and the places that misunderstand them. Then it’s off to a gala in the city to celebrate her selection for Time’s 100 most influential people of the year, where she’ll rub shoulders on the red carpet with personalities like Dua Lipa and Patrick Mahomes.

But when I meet her, on a swampy early spring day in Gainesville, Florida, Groff isn’t thinking about her glamorous New York appointments. She’s wearing Birkenstocks and lugging boxes around her nearly completed book store.

The shop is situated in an old building that in the 19th century housed a cotton gin. It’s the newest storefront in historic downtown Gainesville, just a mile from the University of Florida. When it is done, the Lynx will be a literary hub and independent bookstore devoted to selling challenged and banned books and titles by authors from marginalized groups.

The idea for the store has lived in her head for years, but she’s held the keys to this place since December — roughly the last time her life wasn’t going a mile a minute.

“I haven’t slept in six months,” she says with a smile, shuttling boxes around the store and shelving new releases, pausing to greet admirers and sign their books. It’s five days before the store’s April 28 opening.

Groff is opening the Lynx now to plant a flag in her adopted home state, where she worries free thought is becoming increasingly endangered.

An acclaimed author plants something new

This isn’t just any bookstore, because Groff isn’t just any bookseller. She’s a three-time National Book Award finalist and one of Florida’s most acclaimed living writers. She’s published bestselling novels like “Fates and Furies,” a diptych that documents a marriage from the perspective of both spouses, and “Matrix,” historical fiction set in a 12th-century French convent.

Groff’s most popular work hits closer to home. Her 2018 short story collection “Florida” meanders through the state, following tales of a neglectful father who loves snakes, little girls who narrowly evade death on a deserted island and a mother’s love-hate relationship with Florida itself.

The collection has flown off the shelves recently because of its appearance in, of all things, a Taylor Swift song. Its co-writer Florence Welch revealed she based her verse in Swift’s song “Florida!!!” on one of Groff’s stories, about a wine-drunk woman who keeps seeing ghosts of the men she’s loved in her home as it falls apart during a hurricane.

Groff loves Gainesville. Originally from New York state, she has a connection with the spirited college town where she’s raised her children and found a community of fellow literature lovers.

It’s a connection I feel, too. I lived in Gainesville for years as a student and immediately felt at home among its plucky residents and plentiful alligators.

But she and her neighbors are increasingly concerned about laws Florida’s government is passing that make it easier to ban books, restrict what can be taught about Black history and limit the rights of LGBTQ residents.

The city needed a new stronghold against these threats, and Groff knew she was the person to make it.

“A bookstore is the central nexus for a place, the link between communities,” she says. “And we are watching. We want them to know that there are people watching — they’re not going to get away with it without a lot of protest, and we’re building a community to protest.”

Her work on the bookshop has been frantic, fulfilling and increasingly necessary as challenges to books in her state keep coming. If she had a mission statement, she says, it’s a quote from Heinrich Heine, a 19th century German poet: “Wherever people burn books, they will ultimately burn people.”

If it’s up to her, Gainesville — and Florida — won’t burn.

Why Florida needs the Lynx

There’s something about Florida that grafts itself onto a writer’s bones. Groff isn’t originally from Florida, but I am, and the way her book “Florida” captures my home state is the way I know it: Menacing and gorgeous, hostile and warm — a place where snakes can stalk you from your backyard and ducklings can hatch mere feet away from them. Here is where the lynx rufus, or bobcat, prowls in the heavy night air.

When the wild cat with tufted ears and cropped tail darted in front of Groff’s car one evening, it felt like a sign. She had found a name for her dream, one that had teeth. On the outer wall of The Lynx bookshop is a mural of the animal with a message: “Watch us bite back.”

Groff understands Florida, in all of its confounding and infuriating glory. She knows that the things that live here are hard to conquer.

“What we want to do is create a lighthouse so that, nationally, people know that Florida is not full of closed-minded people,” Groff says.

“So that they know that there are places here that love and welcome transgender people, people who want to learn about Black history, people who want to pay homage to what actually happened, even if it makes us feel bad.”

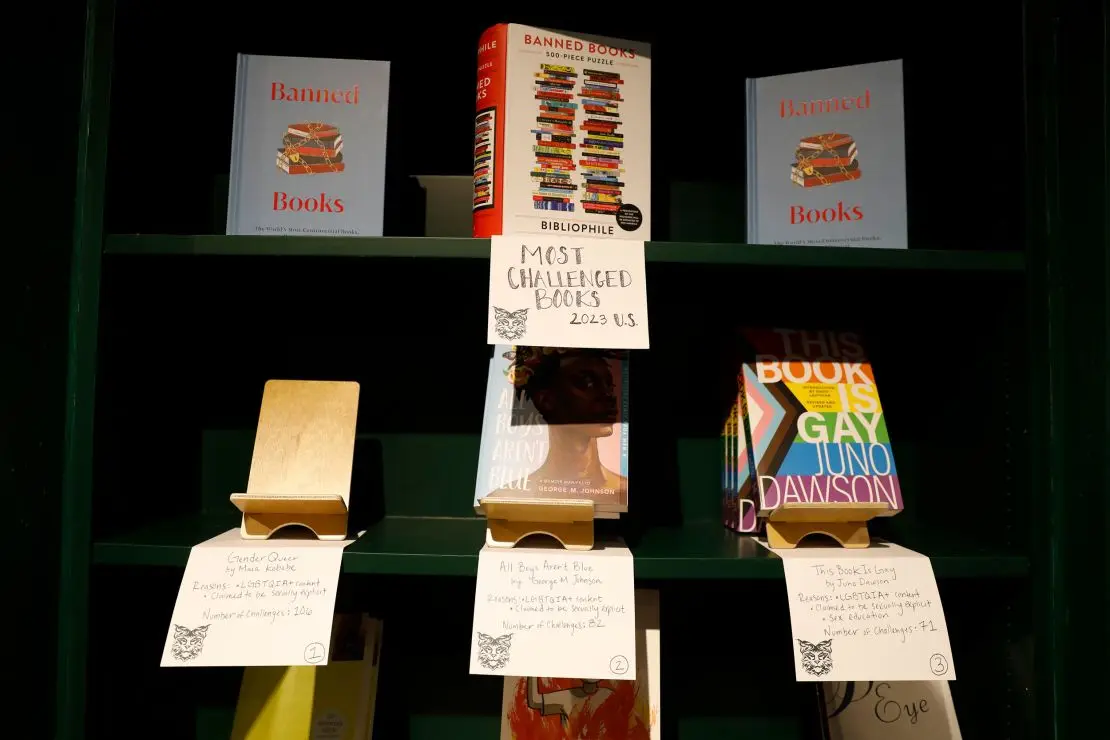

Once a dream, Groff’s vision of a bookshop with purpose acquired new urgency as she observed what she calls “authoritarian creep.” Florida led the country in attempted book bans last year, with 2,672 challenges, the American Library Association reported. Between July 2021 and December 2023, Florida accounted for over 5,000 bans, PEN America found — the next highest state, Texas, had just over 1,500.

With this in mind, the Lynx will be a store first, but also a meeting place for community organizers, a haven for young people in search of books that reflect and affirm who they are and a symbol for Floridians who refuse to bow to discriminatory laws.

“We’re watching what’s happening,” she says. “We want them to know that there are people watching — they’re not going to get away with it without a lot of protest, and we’re building a community to protest.”

She’s not alone in her defense of books

With the Lynx, Groff joins a small but passionate group of independent booksellers in Florida who defend against what Groff calls an “intellectual freeze,” where uncomfortable ideas and topics are silenced.

Mitchell Kaplan, who founded the Miami-based indie chain Books & Books in 1982 as well as the Miami Book Festival, is thrilled that Groff is formally joining their numbers.

“I’ve never felt a more poignant time than now (for) the importance of a bookstore which acts,” Kaplan says. “Most good independent bookstores act as conveners, to bring people together to resist.”

There are other independent bookstores and advocacy organizations in Florida with missions like the Lynx. Gainesville hasn’t had a new one in years until now. The Lynx’s power is in its symbolism, Groff says, existing in rebuke of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and his supporters’ efforts to minimize perspectives by removing them from classrooms and libraries.

“There have always been pockets of people trying to limit the distribution of books,” Kaplan tells me. “But they usually come from real fringe elements. And now, unfortunately, those fringe elements are in our government.”

Intellectual freedom in the state came under severe threat in 2022, when DeSantis signed the law known to its opponents as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, restricting discussion of sex and gender identity in schools. (A legal settlement in March allowed discussion of those topics in classrooms under certain circumstances.)

Also in 2023, the state passed HB 1069, which allows residents of a district to object to books that contain sexual content if it’s not being taught in a health class, which can lead to the bans of books that discuss sexual assault. The state also last year made significant changes to the way Black history is taught in classes: When Florida high schoolers learn about slavery in the US, they now must also discuss “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

All of those laws have emboldened waves of challenges, overwhelmingly against titles that reflect experiences of Black subjects and people of color or LGBTQ characters.

DeSantis has called the media’s depiction of Florida’s book bans “a hoax.” In February, the governor’s press team said, ”Florida does not ban books, instead, the state has empowered parents to object to obscene material in the classroom.”

Hundreds of books have been removed from shelves in Florida public schools and libraries. Students in Orlando’s Orange County will no longer find Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” in their libraries. Miami removed Groff’s own “Fates and Furies” from shelves in its school district. And in Alachua County, home to Gainesville, books like “Gender Queer,” a graphic novel about what it’s like to be nonbinary, and “Melissa,” a chapter book about a trans fourth grader, are unavailable at libraries and public schools.

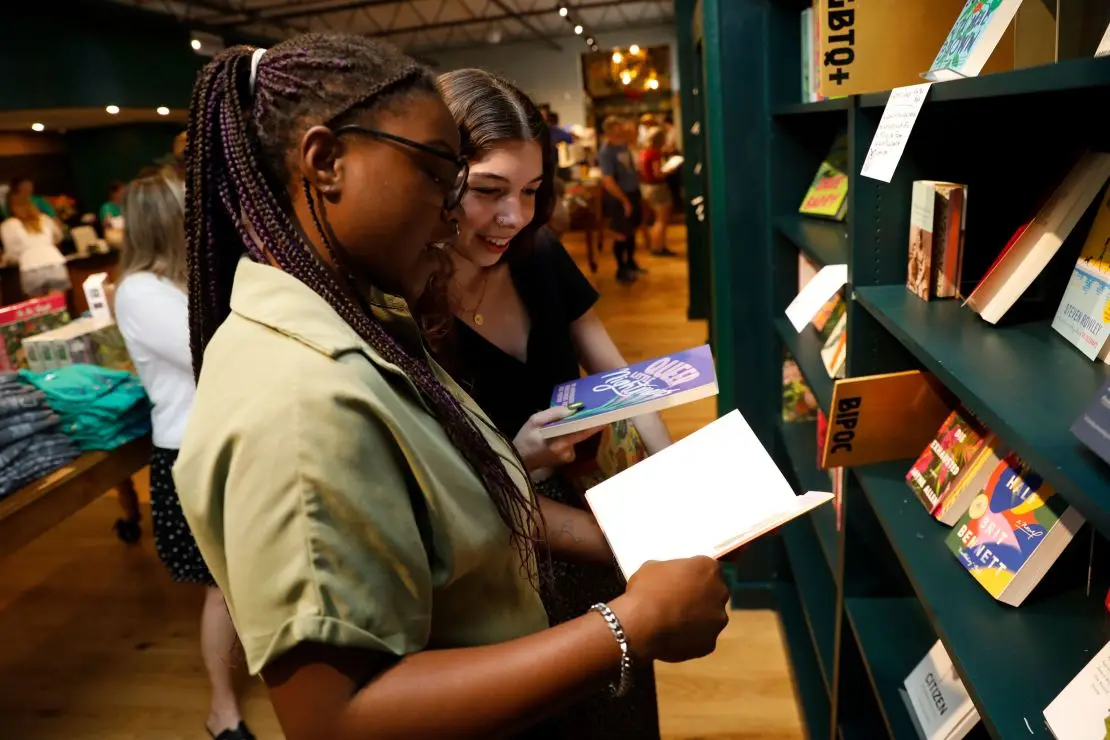

At the Lynx, such titles are a main attraction. Banned and challenged books are on prominent display in the store. The staff has even arranged the 10 most frequently challenged books in the country in numerical order.

Iconic children’s author Judy Blume, who with her husband opened a branch of Books & Books in Key West, Florida, tells me she’s delighted that Groff is becoming a bookstore owner, like authors Ann Patchett, Emma Straub and Blume before her. Her resolve, Blume says, is a necessary tool in the fight against censorship.

“I feel sure that her customers, like ours, will thank her every day for featuring banned books and they’ll ask what they can do to help,” Blume told CNN in an email. “And that’s good news.”

Florida, flaws and all, has sent out roots

Groff resisted Gainesville when she moved here with her husband 18 years ago. Even her body revolted — she doesn’t do well in the Florida sun, and for most of the year Gainesville’s heat is searing. But like the Spanish moss she describes so delicately in “Florida,” the town and its people grew on her. As we sip cafe con leches in an outdoor plaza not far from her shop, we periodically rearrange our Adirondack chairs to stay shadowed from the sun.

“It’s so rich with natural beauty,” she says, dreamily. “You walk around and see these heritage oaks that are 300 years old, with their arms on the ground … Right now the jasmine is blooming, and it smells magnificent. It just perfumes your day. There’s so much to love.”

The city snuck its way into her writing, too. The very first story in “Florida” is set in Gainesville. In it, an unnerved mother goes on long walks in the dark, pounding the misshapen sidewalks in the town’s historic Duck Pond neighborhood, passing streets and landmarks that leap to life in my mind’s eye.

But Gainesville, typically considered a progressive spot in a sea of red, has disappointed Groff lately. The University of Florida recently fired all diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) staff after the state moved to “permanently prohibit” DEI offices from Florida’s public universities. The university’s reputation as a champion of free speech and inquiry has been damaged, and it’s breaking the hearts of Gainesvilleans off campus.

Still, Groff believes the people here will stand their ground.

“Even though right now it’s in the hands of people who want to limit how good it is, and ultimately to whom it is being open and loving, I believe in it,” she says.

She has grand designs for what the Lynx can become. She wants to give books away with her staff, like “the Dolly Partons of Gainesville.” (The country legend has donated over 200 million books to children worldwide through her foundation.) She wants to install a book vending machine at the regional airport. She wants to ensure that the people who need the Lynx most — young people whose families don’t accept or understand them, or who don’t have the language to understand themselves — can find it.

“We will be doing a lot of things to get books into people’s hands,” she says. “But just to be a symbol of resistance has given a lot of people courage, to be honest.”

She can’t do it alone. A group of lynx is called a watch, and along with her passionate staff, Groff’s watch has grown in strength and number. Seeing locals and faraway supporters buy a book in person or donate to the Indiegogo campaign that raised over $116,000 for renovations has brought her to tears more than once.

“It’s made me have faith in humanity again,” she says. “It was getting a little dark for a while.”

The store opens with a heaping of hope

Sunday — opening day at the Lynx — kicks off with champagne and trays of mini muffins. The store looks like a gift waiting to be opened. Aside from the 8,000-plus copies of new releases, beloved classics, plays, poetry compilations, cookbooks and wellness manuals, there’s a first edition of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ Pulitzer-prize winning, Florida-set novel “The Yearling,” in a display case. Tiny Progress Pride flags dot the space.

A little over half an hour before she and her team will cut the red ribbon at the store’s back entrance, Groff quiets her crowd of supporters with a handheld microphone, surrounded by the store’s evergreen walls and dark walnut shelves.

“The pun in our name is just apt at the moment,” she says. “Look at how we’re already the links between so many communities.”

She’s astounded by the small crowd, which includes her beaming parents, neighbors and their young children, her publishing team in town from New York, high school students volunteering for service hours and admirers who contributed to the campaign that pushed the Lynx out of Groff’s head and into a Gainesville storefront. Even Harvey Ward, Jr., Gainesville’s mayor, is in attendance.

We’re whisked out of the store for a few minutes while Groff and her team tidy up with their booksellers. They reemerge outside with a pair of scissors, ready to cut the ceremonial ribbon.

“We’re here today because we love Gainesville, and we love every single one of you,” Groff tells the crowd, which thrums with happiness. It is warm, and the sun is in her face.

Watching the Lynx finally open its doors reminds me of the final story in “Florida.” It follows a mother of two, a writer who sounds an awful lot like Groff, on a weeks-long trip to France with her sons. She’s disturbed by an unknowable darkness inside of her until she realizes, near the story’s end, that she actually doesn’t want to be where she is at all.

Suddenly, she wants more than anything to be back home — a place flawed and infuriating and desperately hot but beloved nonetheless.

“Of all the places in the world,” Groff writes, “she belongs in Florida.”