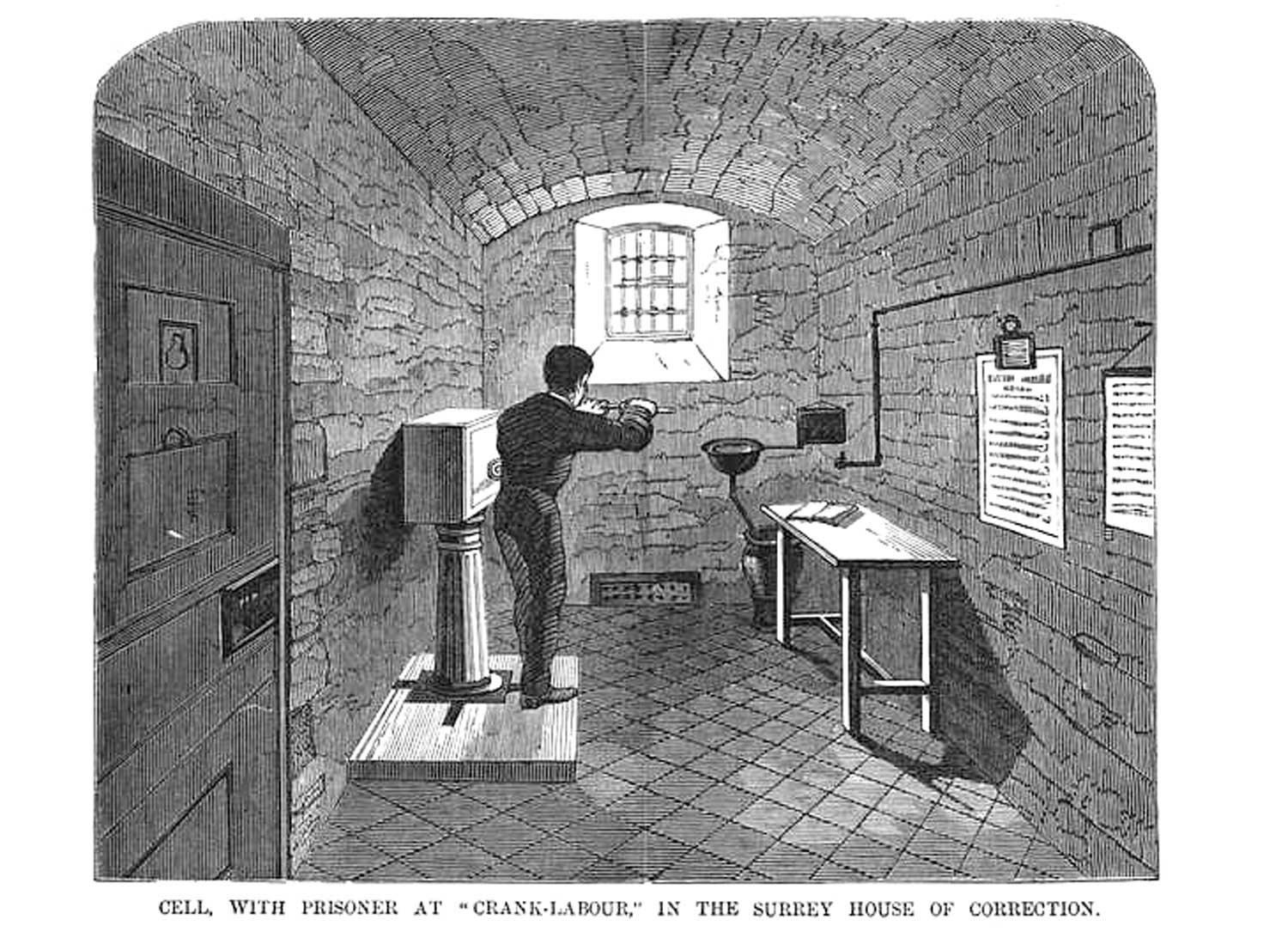

In the grim confines of 19th century British prisons, wardens sought ever more sadistic ways to punish inmates through forced labor. One diabolical device they landed on was the crank machine.

The crank was a hand-powered rotary mechanism that served no purpose other than to torment prisoners. Locked in isolated cells, inmates had to turn a crank handle connected to paddles that churned sand inside a box. The only output was soul-crushing tedium.

Wardens could crank up the cruelty quite literally by tightening a screw to increase resistance on the rotary mechanism, making it vastly more difficult to turn. This simple adjustment earned them the derisive nickname “screws” from hapless inmates.

To earn basic sustenance like food and water, prisoners were expected to complete a 10,000-14,000 revolutions per day on the crank, often working late into the night by candlelight if they fell behind quota. Failure meant starvation and exhaustion, making the next day’s ordeal even harder.

The crank exemplified the Victorian penal philosophy that unproductive, mindless toil was the ultimate reformative punishment for criminals. Mercifully, the crank machine faded from use by the early 20th century as more humane concepts of rehabilitation took hold.

But for decades it personified the grim injustice and arbitrary cruelty faced by British convicts, some imprisoned for mere poverty, who succumbed to this insidious instrument of psychological torture. The crank’s legacy of brutality is a haunting reminder of a penal system’s capacity for institutionalized sadism.

Previously: Useless Machine eventually surrenders