With the success of movies like Femi Adebayo’s 2023 Netflix epic, Jagun Jagun, it is clear that we’re witnessing a Yoruba language renaissance in film, especially through works that are created to acknowledge the intellect of their audiences. Seeing this, the question arises: Can Yoruba literature enjoy the same fate?

I had my first taste of Yoruba literature, particularly the novel form, during a Christmas visit to a great-aunt in 2009 when my family moved to Ibadan in Oyo State. Already a bibliophile who had also mastered the Yoruba diacritics/tonal marks, I found Alágbárí, amongst the huge heaps of books in the room where her husband stored the books he distributed. I remember being so enthralled by this novel that I no longer cared for the merriment going on around me. My great-uncle, impressed, ended up gifting me the book since I couldn’t finish reading it by the time we were leaving two days later. The second novel I would read was Debo Awe’s Kanna Kánná which I borrowed or more accurately, rescued from mouldering in an aunt’s house. I would go on to read many more novels I could find―which constituted the ones from my school’s library, the ones someone’s parents or much older siblings used in primary and secondary schools, and the rejected ones I rescued from the people’s houses or worse, dusty grounds. However, I didn’t get completely exposed to the works of renowned writers like D.O Fagunwa, Adebayo Faleti, and Oladejo Okediji until Àkàgbádùn.

An ardent radio listener residing in Ibadan from the year 2011/12 would need no introduction to Bade Ojuade’s Àkàgbádùn, a Yoruba book-reading radio programme that aired for an hour every Tuesday on Oluyole FM, one of Oyo state’s famous radio stations. The programme kicked off with Lawuyi Ogunniran’s Eégún Aláré, with Bade Ojuade, a seasoned Yoruba linguist himself, reading, alternating between characters whose dialogues he read in the respective Yoruba dialects he gave them. Eégún Aláré captures the lives of performing masquerades and is therefore replete with ẹ̀sà, the Egungun chant which Ojuade also performed. This became my first contact with that aspect of Yoruba oral literature. The programme would go on to feature Adebayo Faleti’s Ọmọ Olókùn Ẹṣin, Oladejo Okediji’s Àjàlólẹrù, Bamiji Ojo’s Ọba Adìkúta, and Mẹ́numọ́ before my family’s commitment to it dwindled. The programme was rescheduled to air for 30 minutes on Thursdays and Fridays. This, being quite difficult to keep up with, in addition to the boom in the Nigerian Afrobeats music scene swayed our interest. By the time we grew blasé from our music adventure and tried to go back to being the devoted listeners we were, we discovered the programme was no longer airing.

‘The programme was discontinued in 2019 because I, alongside other people, left the Broadcasting Corporation of Oyo State (BCOS) due to some occurrences that we were not comfortable with,’ Bade Ojuade told me.

He further reveals that on returning to BCOS in 2020, following the intervention of the Oyo State governor, Seyi Makinde, he was not allowed to take over the programme from the broadcaster who had carried on with it due to what he described as workplace politics.

One of the significances of Ojuade’s Àkàgbádùn was that the listeners were exposed to classic Yoruba novels. Alongside being entertained, his appropriate rendition of the different forms of Yoruba oral literature in the novels further enriched our knowledge of it. The interest of the Oyo State-owned media in upholding Yoruba language and literature birthed the programme. For Ojuade, when the book-reading programme was suggested to him by BCOS management, accepting it also meant fulfilling his desire to read Yoruba literary texts on the radio. He would then quit his freelance programme, Ọpọ́n Ayé, coin Àkàgbádùn, as opposed to Àyọkà, which was suggested by the station, and kick off with it at Oluyole FM.

The success of Ojuade’s programme can be traced to his ability to blend the phonocentric quality of Yoruba orature with the reading of written literary texts. This, he confirmed, saying ‘people tell me they enjoy my programme more due to my innovative infusions like the performance of the oral literature and the use of different dialects for the characters.’

Although the book reading programme is now being continued at Oluyole FM and it still retains the name ‘Àkàgbádùn’, these qualities that endeared many listeners to it in the first place are being neglected, denying people the full pleasure of experiencing Yoruba literature. Just like this programme, I’ve witnessed how this ‘relative access’ to Yoruba novels I had while growing up diminishes or gets tampered with by the day for different reasons, restricting each younger generation’s interaction with Yoruba literature to only in classrooms and within the recommended list in the Nigerian school curriculum.

Since language is the vehicle for literature, one of the ways changes can be effected is by a provision that ensures schools in the Yoruba-speaking region of the country are tasked with fostering Yoruba language literacy and fluency among their students. To this effect, a major effort by the Nigerian government is the approval of the new educational National Language Policy that provides that students, throughout their elementary level, be taught in the indigenous language of the community where their school is located. Then, at the junior secondary level, the mother tongue will be combined with the English language as the medium of instruction. However, the faults in the policy and its near ineffectiveness since it was announced on November 30, 2022, by the then Minister of Education, Adamu Adamu—a lot of work is required to implement it as Adamu had stated has hardly begun—shows how much of a performative participant the Nigerian government is in preserving indigenous languages.

FOR WHOM WILL THE YORUBA WRITER WRITE?

Yoruba written literature is highly influenced by the missionary and colonial presence in southwest Nigeria. Book publications in the Yoruba language began with Bibeli Mimo (1900), the Yoruba translation of the English bible, and a five-part reader series (Iwe Kika Ekini – Ekarun), which according to historical assertions were religiously motivated actions as the aim was to further spread the Christian religion among the Yoruba people and ingrain its gospel in their minds. It then progressed to include secular literary works, a development that produced the aforementioned popular literary figures most of whose works witnessed warm acceptance and wide readership at the time they were published.

Regardless of the intention behind the earliest translated English texts to Yoruba and writing in Yoruba, it sends a message that a people’s language is the clearest path to reach them, and its expansion to include actual literary works in Yoruba stemmed from the demand of a people who treasured their language to an extent, a quality that continues to fade with each passing generation, hence the number of Yoruba literates and proficient speakers keep lowering. Acknowledging this opens the conversation to include an important question: for whom will the Yoruba writer write?

The reading culture in Nigeria is argued to be poor and waning. UNICEF’s 2022 data shows that 1 in 3 Nigerian children are out of school. This is compounded by another UNICEF report that states that 3 in 4 pupils are unable to read with comprehension. Per the most recent Federal Government statistics, also in 2022, 31 per cent of the population are unable to read and write, indicating a decrease from 38 per cent in 2018. This, if it continues, combined with the rate of child illiteracy, suggests that Nigeria might be a long way from achieving the UN-established Sustainable Development Goal 4 and its targets to ensure that everyone has equal access to quality education by 2030. This identified low literacy rate among Nigerian youths and adults, aliteracy, and the luxury which buying books have become given the poor state of the economy as part of the factors that may keep this problem around. If the number of the few readers across the country is then narrowed down to the number of people who read Yoruba literature, the contemporary Yoruba writer cannot boast of a large and committed readership.

One might argue that the Yoruba language is thriving currently. Because it is one of the most widely spoken languages in the country, there is a rise in the use of Yoruba buzzwords nationwide. The heavy influence of the language on Afrobeats is being recognised. The movie industry is also populated by works containing the presence of the Yoruba language and this has even progressed to the production of movies in which Yoruba is the only communicative medium for general consumption. All these, however, do not guarantee the safety of the Yoruba language. Why? The weakened intergenerational transmission of the language, alongside the dominance of the English language is a largely responsible factor. These can be traced to highlighted challenges like the general negative attitude to the acquisition of indigenous languages (Yoruba, in this case) in Nigerian homes, both in the country (especially in urban areas) and abroad. There is also an analysis of how the Nigerian schools and educational system, in particular, contribute to this setback.

Obviously, Yoruba literature requires the participation of not just fluent speakers but literate language users to thrive. If this population is low and there’s little appreciation for the literature, whether oral or written, the Yoruba writer’s reward would most likely be readers in their lowest possible numbers.

FOR WILL YORUBA LITERATURE EVER RISE AGAIN?

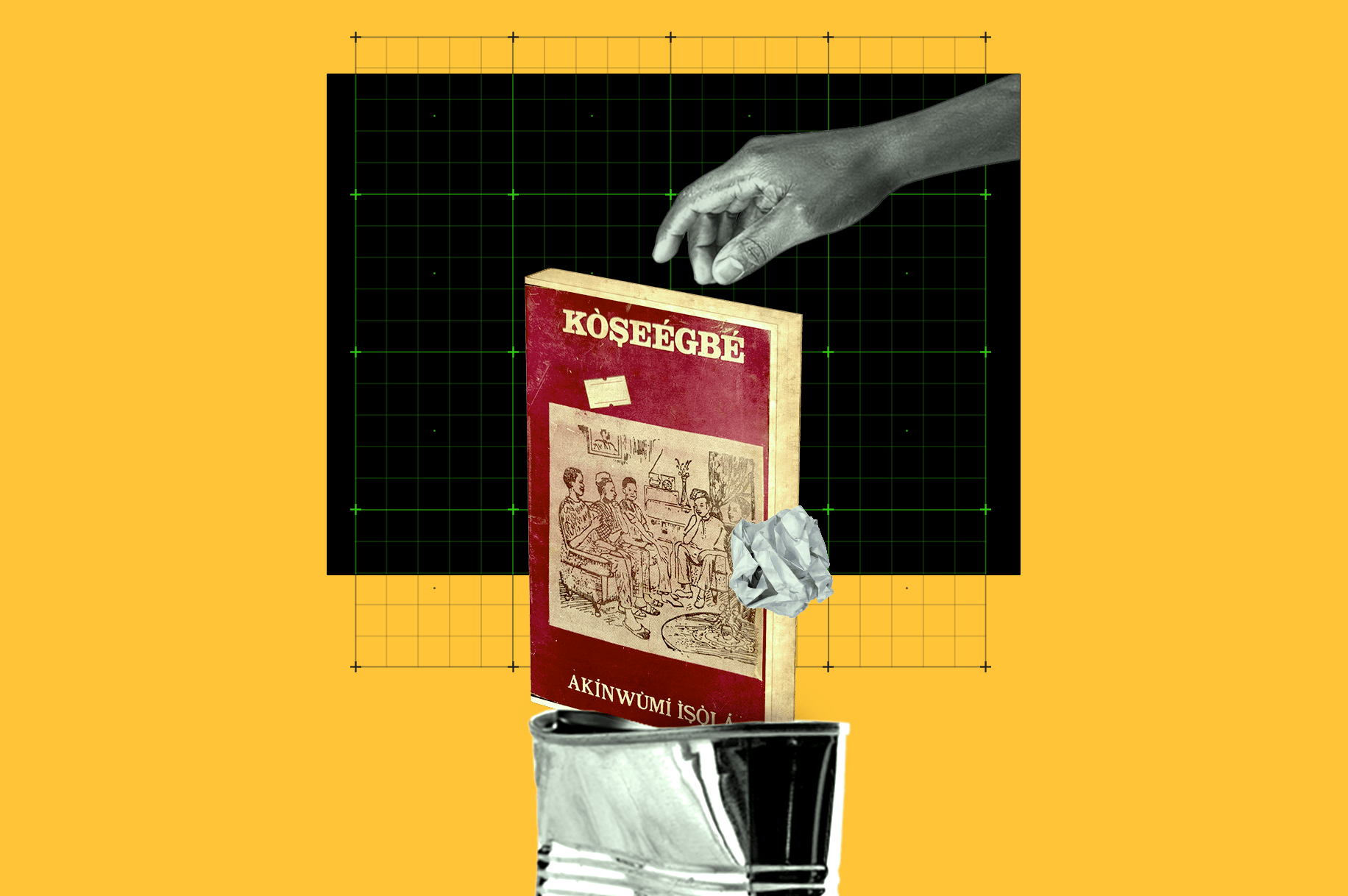

A classmate gifted me Okediji’s Àjàlólẹrù for my birthday in 2021. This was when I realized that it has a sequel, Àgbàlagbà Akàn, so I set out to find it. After several disappointing visits to the bookshops—which included two prestigious ones in Ibadan—I realized that the novel was no longer in circulation. My question of why this book and many others like it are no longer readily available is answered by Ibrahim Oredola, a Yoruba language and culture enthusiast and the co-founder of Àtẹ́lẹwọ́, a platform that promotes Yoruba culture and literature, who explains that this a problem resulting from publishing being viewed from an economic lens. He says: ‘There are a lot of books that are gems but are no longer in print because the publishers believe that they won’t sell fast, therefore it doesn’t make economic sense to keep publishing them anymore.’

One might also question if there are (emerging) contemporary Yoruba writers telling stories that meet up with the quality of their forerunners as there is also a noticeable decline in the few newer published works. To this, Oredola answers in the affirmative, explaining that over the years, Àtẹ́lẹwọ́ has received many dazzling stories submitted by writers for publication on the website. This is also the same for the annual Àtẹ́lẹwọ́ prize for Yoruba literature for which over 70 full book-length manuscripts have been submitted by writers since its inception about three years ago. He, however, explains that publishers are not willing to publish these works or newer titles unless they’re recommended for students in the educational curriculum or for particular examinations because it’s not financially rewarding. He says:

They believe there’s no market for it and they most likely are not wrong. So, it becomes challenging for new voices to get a publisher for their works. Since the readership population has declined, the publishers are not ready to ‘risk’ publishing new voices because to them it’s just a matter of numbers.

This becomes a full circle of obstacles. The low number of Yoruba novel readers means there is no market for it as publishers claim, consequently leading to the continuous unavailability of books. How then do we witness growth in the number of readers and potential writers since reading helps better one’s spoken and written ability of a language as Oredola puts it? The struggle to keep Yoruba literature is two-sided: on one hand, is the fight to rescue the language from its state of being endangered, and on the other hand, is the effort to publish more creative works and make the published ones accessible.

There has been a longstanding debate about the language to be used for African literature. On one side is Obi Wali’s famous 1963 argument that ‘any true African literature must be written in African languages.’ This was countered by Chinua Achebe who opined that the English language should instead be domesticated to suit our African context. Wali’s position was supported years later by Ngugi wa Thiong’o who called for the linguistic decolonisation of our (African) minds.

At the literary level, Yoruba literature again faces competition from literary works published in the English language which is Nigeria’s official language and is, therefore, more accessible by people across languages as Achebe had argued. Consequently, manuscripts written in English stand a higher chance with Nigerian publishers than one in any indigenous language, particularly Yoruba, and this forms part of the explanation for why Nigerian literature in English far outnumbers ones in any indigenous language and why even I, a lover of Yoruba literature would read tens of works written in English before accessing one written in Yoruba.

Save for the poorly implemented and ineffective national language policy which provides that mother tongues become the medium of instruction for the first six years of learning in all Nigerian elementary schools, the preservation of the language is mostly fronted by individuals and private organisations.

Àtẹ́lẹwọ́, for instance, features a literary magazine publishing various genres of works by Yoruba writers and the aforementioned annual prize competition which serves as an encouragement to new writers. This cannot be underestimated as one of such competitions organized by the Western Regional Literature Committee for the Nigerian Independence celebration in 1960 led to the publication of the winning manuscript, Olówólaiyémọ̀, Femi Jebooda’s debut novel.

Over the years, I’ve witnessed the works of linguists like Kola Tubosun who contribute to the development of the Yoruba language at the intersection of language and technology and also contribute to the literature by translating works written in English to Yoruba. One of his notable works, his second poetry collection, Ìgbà Èwe, is a Yoruba translation of Emily R. Grosholz’s 2014 poetry collection, Childhood. Last year, I discovered that Ojuade resumed anchoring Àkàgbádùn on Agidigbo, a private radio station in Ibadan. There are also young people utilizing social media as a tool to explore audio-visual storytelling and various forms of Yoruba literature and to correct myths and misconceptions within the language, culture, and its literature.

Despite all these efforts from these language enthusiasts—in the face of the harsh Nigerian realities that steal the passion for literature from people before they even suspect, fuel them with the struggle to survive, or even uproot them from the country, a situation that has recently awakened debates on whether Nigerian literature (in English), in its abundance, is dying—there’s no end to the questions badgering my mind: can the audience for Yoruba literature possibly be widened especially through fostering literacy in Yoruba language? Alongside this, what more will save Yoruba literature from its current state? How much more needs to be done?⎈

The views, thoughts, and opinions published in The Republic belong solely to the author and are not necessarily the views of The Republic or its editors. We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editors by writing to [email protected].