Who are the greatest and most famous astronomers of all time?

The history of astronomy is the story of how humanity has uncovered the secrets of the cosmos, from early astronomers defining the mechanics of the Solar System and how the night sky changes over time, to astrophysicists studying the chemistry of stars, the expansion of the Universe and the warping of spacetime.

Of course, no single astronomer can strictly be deemed ‘the greatest’.

Astronomy – like all science – is an accumulative and collaborative effort, each new generation building upon the successes – and mistakes – of the past.

Here we’ve listed some of the most famous astronomers in history: those men and women who revolutionised our view of the night sky, and helped us understand a little better our own place in the vast cosmos.

50 famous astronomers you need to know

Hipparchus (circa 190–120 BC)

Hipparchus was a Greek mathematician and astronomer. None of his works has survived, but we know of them through Ptolemy, last of the ancient Greek astronomers, who made a star catalogue in 140 AD.

After seeing a nova in 134 BC, Hipparchus catalogued the positions of 850 stars in case another popped into view. By comparing his values with some made 150 years earlier, he discovered the precession of the equinoxes. He also founded the stellar magnitude system we use today.

Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century AD)

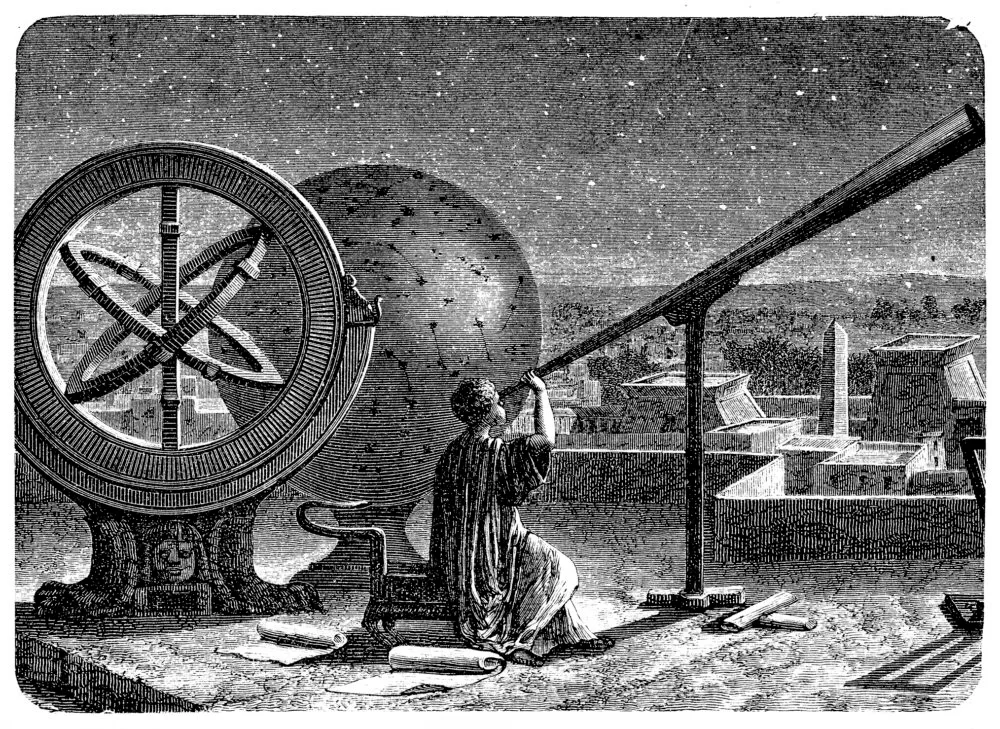

Ptolemy of Alexandria, arguably the greatest astronomer of antiquity, wrote a sweeping synthesis of the astronomical philosophy of the ancient Greeks.

His great book, the Almagest, is a work of awesome complexity in which he represents planetary motion through interlocking circular orbits, with Earth at the centre of the Solar System. This work was the standard textbook on planetary motion until the 16th century, when Copernicus introduced the heliocentric model.

Hypatia (c350-415)

A gifted and greatly respected teacher, Egyptian polymath Hypatia (c350–415) was in her time the world’s leading astronomer and mathematician. The widely-educated daughter of the mathematician and Euripides scholar Theon of Alexandria, one contemporary said she “far surpass[ed] all the philosophers of her own time”.

Although none of her writings survives, she is thought to have edited Book III of Ptolemy’s Almagest, a manual on the motions of the stars and planets, and to have constructed astrolabes.

Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543)

Copernicus wrote one of the most influential books of all time, De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (best known as De Revolutionibus). Daringly, Copernicus the revolutionary showed that planetary motions could be accounted for in a world system with the Sun at the centre.

His change of perspective from the Earth at the centre to the Sun in prime position deeply challenged Christian beliefs. Acceptance of his model didn’t come until nearly a century later.

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601)

This Danish nobleman unfortunately had his nose hacked off in a duel. A respected astronomer, astrologer and alchemist, his careful observation of the nova of 1572 sparked his interest in astronomy.

By noting that the new star did not change position from night to night (it was far away) he shattered the crystalline Universe of the ancient philosophers who had maintained that the Universe beyond the Moon was perfect and unchangeable.

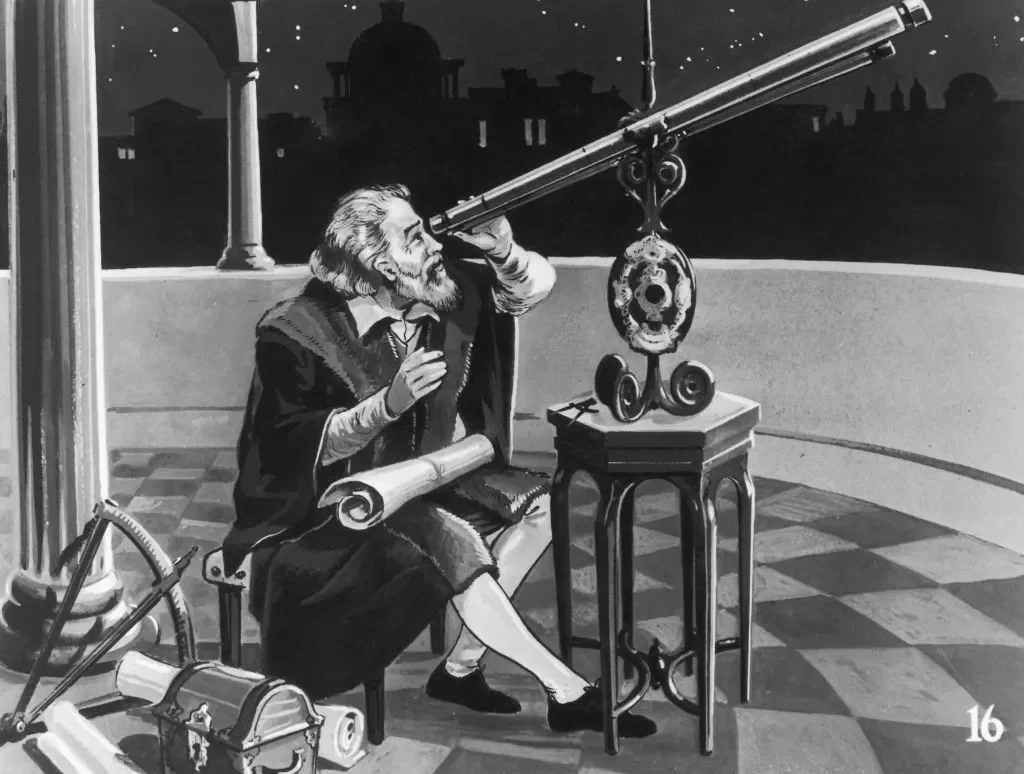

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

Undoubtedly among the most famous astronomers of all time, Galileo constructed a simple refracting telescope in 1610 and became the first person to use a spy-glass for astronomy. The sheer number of stars, the rough surface of the Moon and sunspots astonished him.

He quickly discovered the Galilean moons of Jupiter and observed the phases of Venus. Everything he saw agreed with the Copernican system which he openly proclaimed, despite strong opposition from the Church.

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630)

Johannes Kepler broke free of the classical tradition in astronomy, preferring the methods of science to the thoughts of the ancient sages. In 1600, Tycho Brahe (who had compiled precise observations of Mars) asked Kepler to examine its orbit.

Eight years later, he found not only that it was elliptical, but that all the other planets have elliptical orbits too. Kepler also observed a star in 1604 that suddenly brightened. Now called Kepler’s star, it was the last supernova seen in the Milky Way.

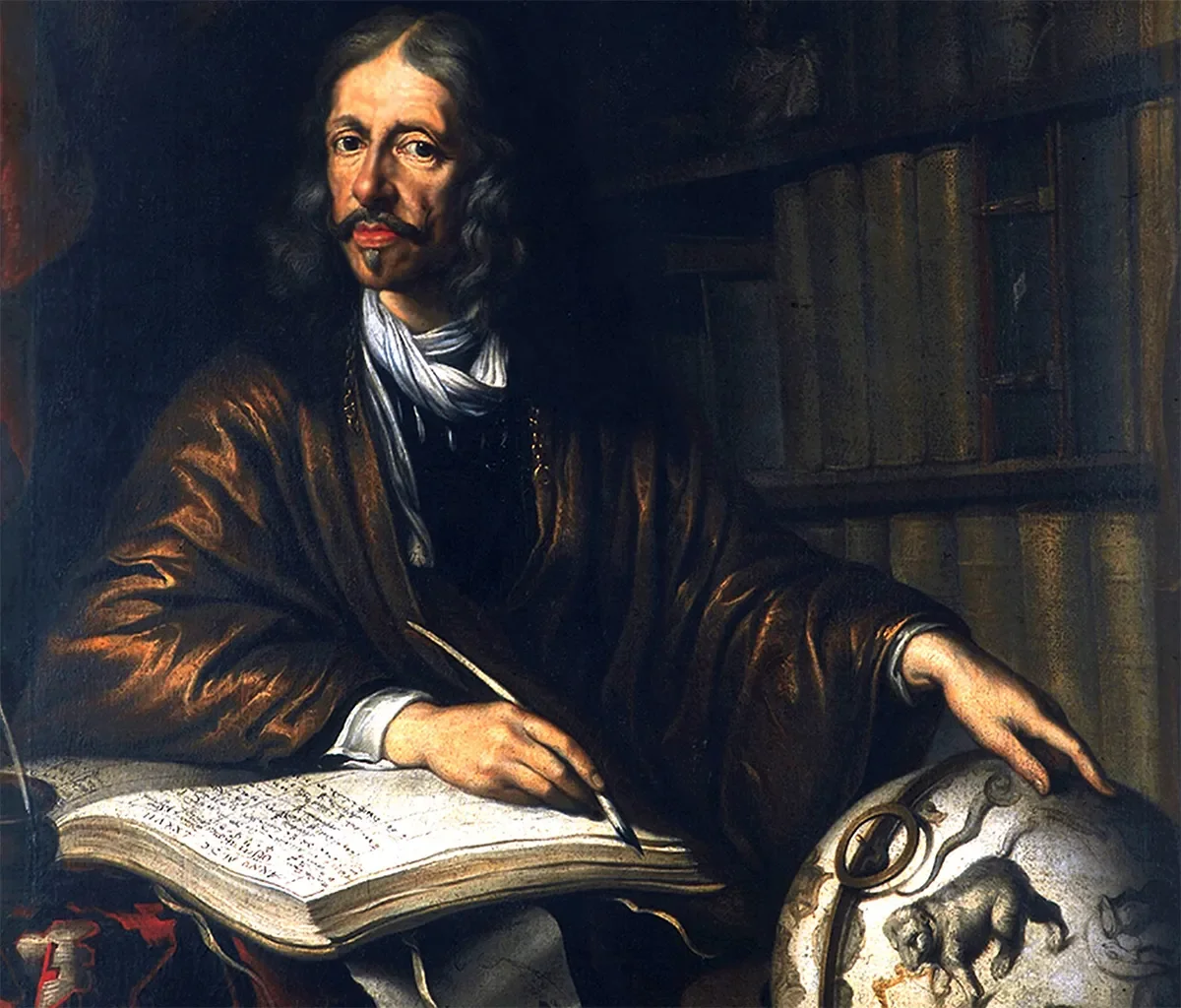

Johannes Hevelius (1611–1687)

Hevelius was a wealthy brewer and councillor who made many observations in his spare time. He constructed a large rooftop observatory that employed an enormous telescope of 130ft (40m) focal length to observe the Moon, from which he drew exquisite maps.

His work in positional astronomy led to a star catalogue of 1,564 stars being published – the most complete of its day. Hevelius used a quadrant for this and was the last astronomer to do major observational work without the aid of a telescope.

Giovanni Cassini (1625-1712)

Italian-born astronomer Giovanni Cassini equipped and directed the Paris Observatory from its foundation in 1671 until his death. His observations were focused around the Solar System, where he measured the distance of the Earth from the Sun to an accuracy of 7%.

It was a truly remarkable breakthrough for the time. He also discovered four of Saturn’s moons: lapetus, Rhea, Dione and Tethys, as well as the gap in Saturn’s rings that now bears his name.

Isaac Newton (1642–1727)

Isaac Newton, one of the greatest scientists of all time, is mainly remembered for his work on gravity. He also made major contributions to astronomy through his work on optics, experimenting with the surfaces of lenses to see if he could eliminate chromatic aberration.

From this research he correctly concluded that either compound lenses or curved mirrors would be needed to reduce colour distortion. Although he made small telescopes to this (Newtonian) design, only later generations of observers benefited.

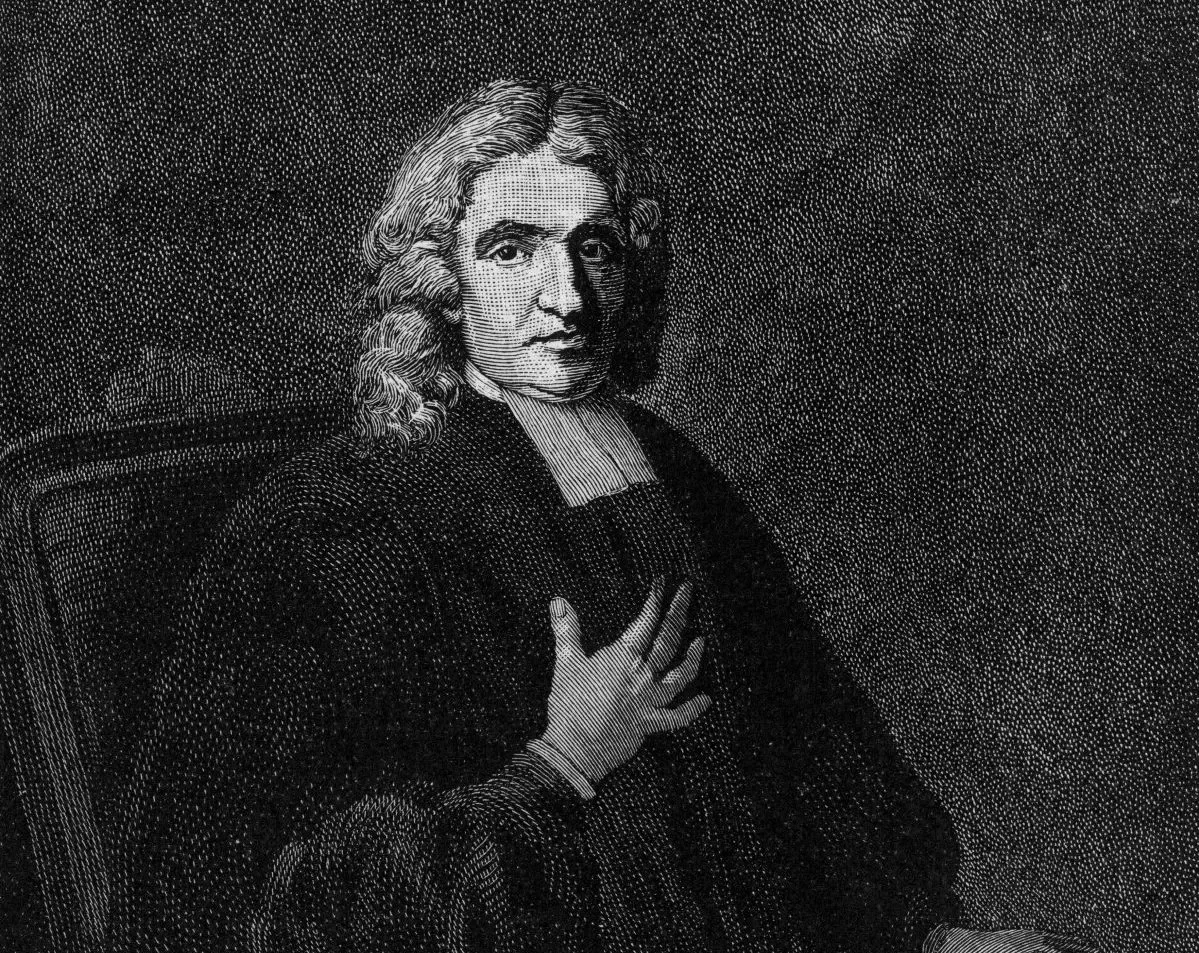

John Flamsteed (1646-1719)

John Flamsteed was hand-picked by Charles II as the first Astronomer Royal. Amongst other duties, his job was to improve astronomical methods for finding longitude at sea. The King’s navy was engaged in a global search for colonies, and desperately needed to improve navigation.

Flamsteed, using star positions for this purpose, designed accurate instruments that he used to make a new star catalogue and a star atlas featuring the positions of 3,000 stars.

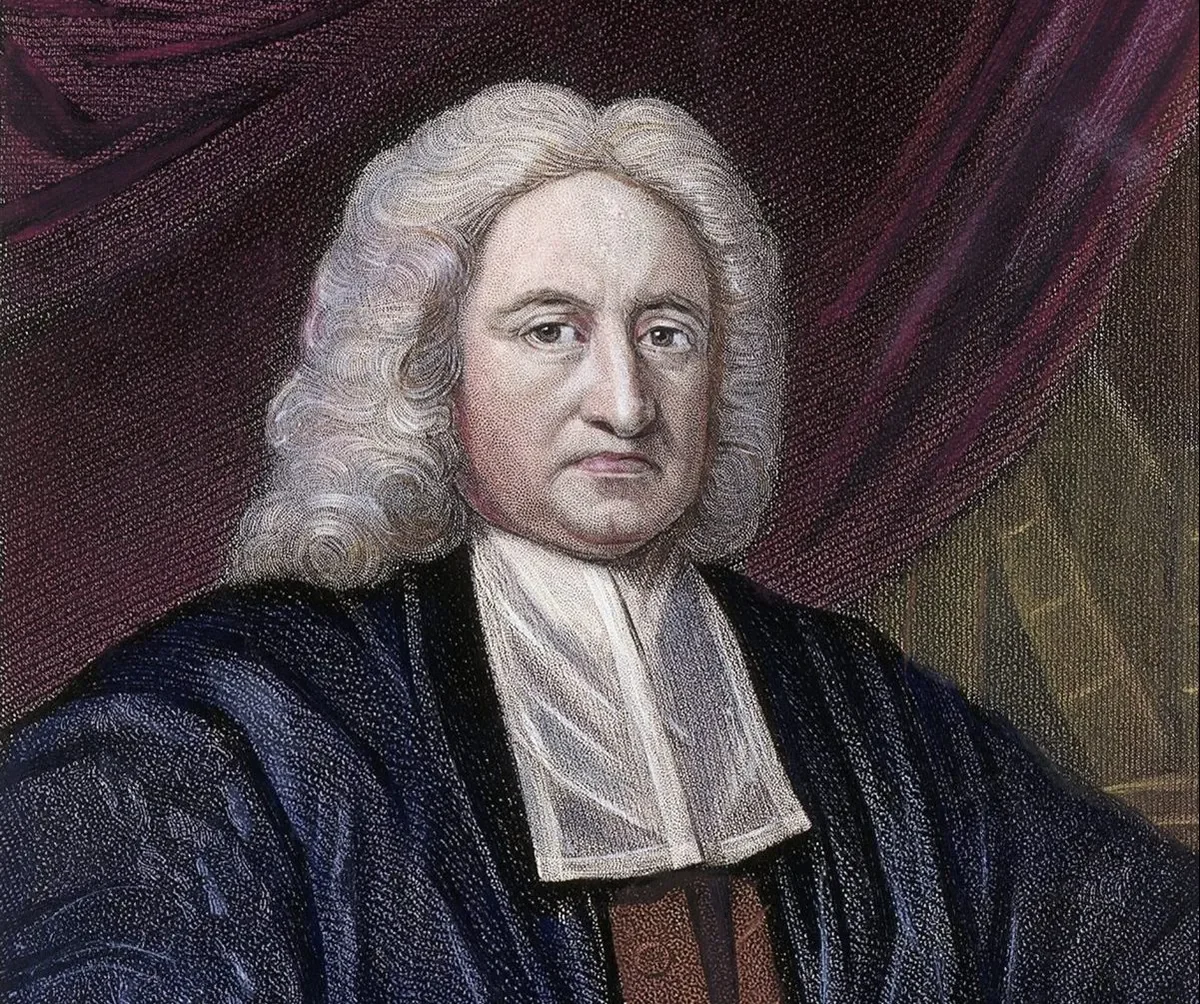

Edmond Halley (1656–1742)

Edmond Halley made enormous contributions to almost every branch of physics and astronomy. Using his knowledge of geometry and historical astronomy, Halley linked the comet sightings of 1456, 1531, 1607 and 1682 to the same object, which he correctly predicted would return in 1758.

Halley would be long dead by then, which is why not everyone took his prediction seriously, but the comet was named after him nonetheless. He died in 1742 but the comet is his lasting legacy.

Nicole-Reine Lepaute (1723–88)

Lepaute, with fellow French astronomers and Alexis Clairaut and Joseph Lalande, calculated the return date of Halley’s Comet, including complex adjustments for the gravitational influence of Saturn and Jupiter.

For many years she compiled ephemerides (tables predicting the future movements) of celestial bodies for the annual publication of the distinguished French Academy of Sciences, as well as writing on the transit of Venus across the Sun and producing a chart predicting the path of the 1764 annular solar eclipse.

Charles Messier (1730–1817)

The dazzling, six-tailed comet of 1744 sparked Charles Messier’s interest in astronomy. He was the finest comet hunter of his time, finding a total of 13. In his sweeps of the sky Messier also netted fuzzy objects that looked like comets but were fixed in position.

To aid fellow comet hunters, he listed 103 of these nebulous objects, which included star clusters, gaseous nebulae and galaxies. This compilation is the Messier Catalogue – a cornerstone of modern astronomy.

William Herschel (1738 – 1822)

Sir William Herschel has quite a few contributions to his name: discoverer of the planet Uranus, pioneer of sidereal astronomy and designer of what was the world’s biggest reflector from 1789 to 1845.

William and his sister Caroline catalogued thousands of deep-sky objects. William categorised them, along the way developing a theory of stellar evolution and estimate for the size and shape of the Milky Way.

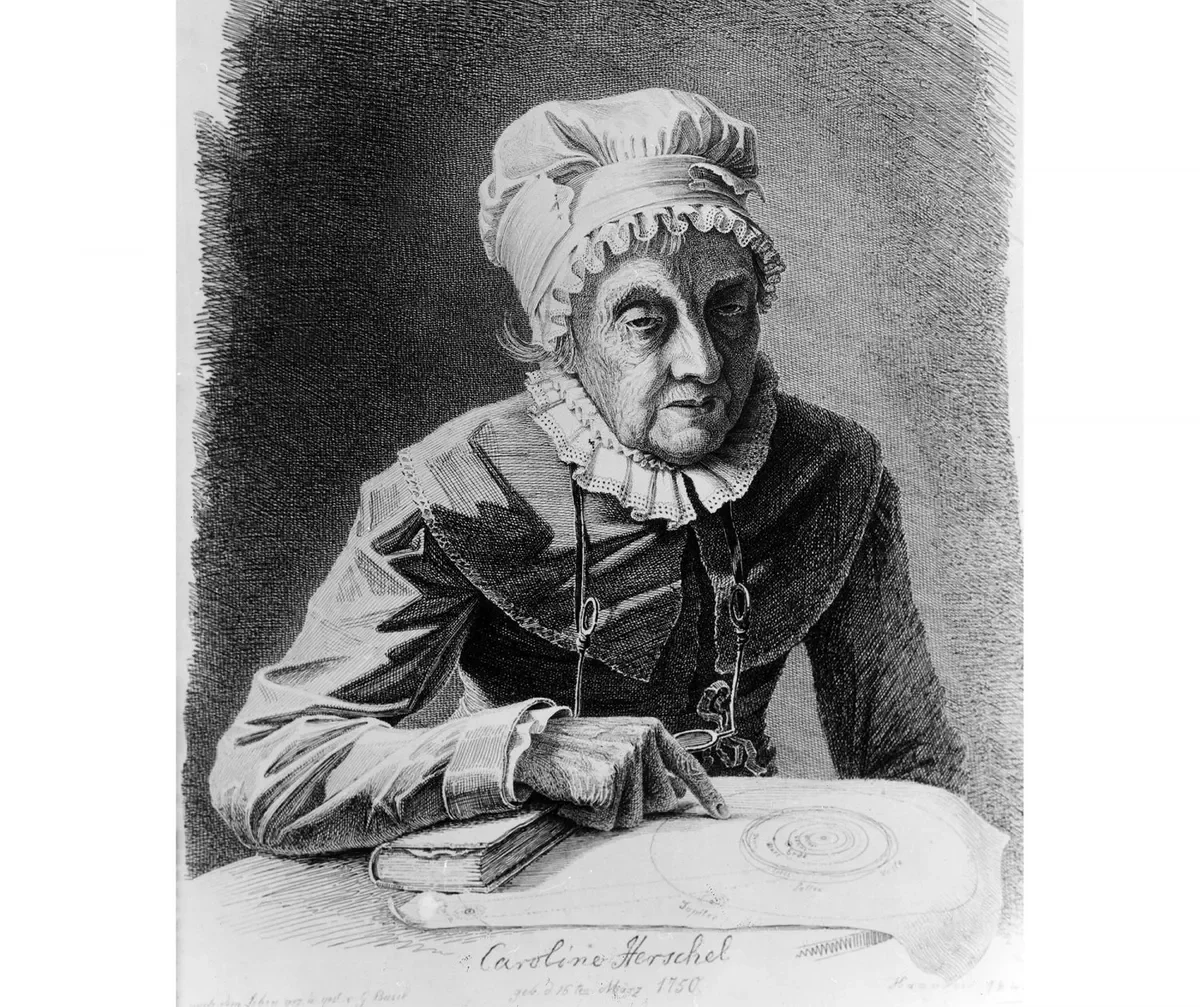

Caroline Herschel (1750 – 1848)

Caroline Herschel achieved many firsts, among them being the first woman to discover a comet (she discovered 8 in her lifetime), the first paid female astronomer and, along with Mary Somerville, the first woman to become a member of the Royal Astronomical Society.

She is also known for her work revising a catalogue of nearly 3,000 stars that had been observed by John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal. She discovered open star cluster NGC 7789, also known as Caroline’s Rose Cluster, and on 16 March 2016 received her own Google Doodle.

Mary Somerville (1780 – 1872)

Mary Somerville was a celebrated scientist of her day who despite the protestations of many of her male peers, published scientific papers on magnetism and the solar spectrum.

She, along with Caroline Herschel, became the first woman to become a member of the Royal Astronomical Society. When she died, she left behind some of the most popular science textbooks of the 19th century.

Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787-1826)

This German physicist earned his living by making the world’s finest glass for telescopes. In 1813, while researching the refractive properties of glass, he accidentally observed dark lines in the solar spectrum. He investigated them intensively, laying the foundations of spectroscopy.

In the yellow he observed a pair of very dark lines, to which he assigned the letter D. These later became known as the ‘sodium D lines’, because the light is absorbed by sodium in the Sun’s atmosphere.

John Herschel (1792–1871)

John was the son of William Herschel. He studied mathematics at Cambridge, and began to assist his father in 1816. In 1834 he went to the observatory at the Cape of Good Hope to survey the southern skies and, while there, discovered no fewer than 2,000 nebulae and 2,000 double stars.

John found himself in the midst of controversy in 1835, when the New York Sun newspaper spun a hoax to boost its sales claiming that he had found animals living on the Moon.

George Biddell Airy (1801-1892)

Airy trained as a mathematician in Cambridge and directed the university’s observatory from 1828 at the age of 27. As the seventh Astronomer Royal (1835-1881) he reformed the Royal Observatory Greenwich which, by all accounts, he ruled with a rod of iron.

Airy established a new meridian line at Greenwich in 1851, replacing three earlier meridians. At an international conference held in Washington DC in 1884 this became the definitive prime meridian of the globe.

William Huggins (1824–1910)

Huggins founded astronomical spectroscopy, being the first to make intensive investigations of stellar spectra, and was the discipline’s pioneer. In 1863 he was the first to show that stars are composed of chemical elements that occur in the solar spectrum.

That same year he scored another first by measuring the redshift of Sirius, following which he measured the velocities of many stars. Huggins’s spectroscope also proved that emission nebulae are glowing clouds of gas.

Percival Lowell (1855–1916)

Lowell used his personal fortune to make the first scientific search for life on Mars. Starting in 1894 he spent 15 years observing Mars with an excellent 24-inch refractor at his own observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona.

He produced detailed maps of the Red Planet that recorded seasonal variations as well as linear features but, like other planetary scientists of his generation, he interpreted many surface features of Mars as evidence that an advanced civilisation lived there.

Williamina Fleming (1857–1911)

Born in Dundee, Scotland, Fleming devised the Pickering-Fleming system for classifying stars based on the amount of hydrogen observed in their spectra. Abandoned in the USA by her husband while pregnant, she supported herself by working as a maid for Edward Pickering, Director of the Harvard College Observatory, quickly advancing to become a ‘computer’ at the observatory.

She discovered over 200 variable stars and 59 nebulae, including the famous Horsehead Nebula in 1888. She became an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1906.

Annie Jump Cannon (1863 – 1941)

Annie Jump Cannon was an American astronomer who made her name while working as an assistant at Harvard University in the late 19th century. She, along with many other women astronomers, worked on classifying the spectra of stars.

Cannon is responsible for having simplified Williamina Fleming’s spectra classification to classes O, B, A, F, G, K and M, which is now the standard.

Annie Maunder (1868–1947)

A pioneer of solar studies, Maunder was one of the first female scientists employed at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, albeit as a low-paid ‘computer’. During the 1890s she recorded and photographed sunspots and researched eclipses during expeditions to Algiers, Canada, Lapland and Norway.

She captured the first ever picture of streamers from the Sun’s corona using a solarscope of her own design and, alongside her husband Walter Maunder, compiled the famous Maunder Butterfly Diagram that tracked sunspot movements over the course of the 11-year solar cycle.

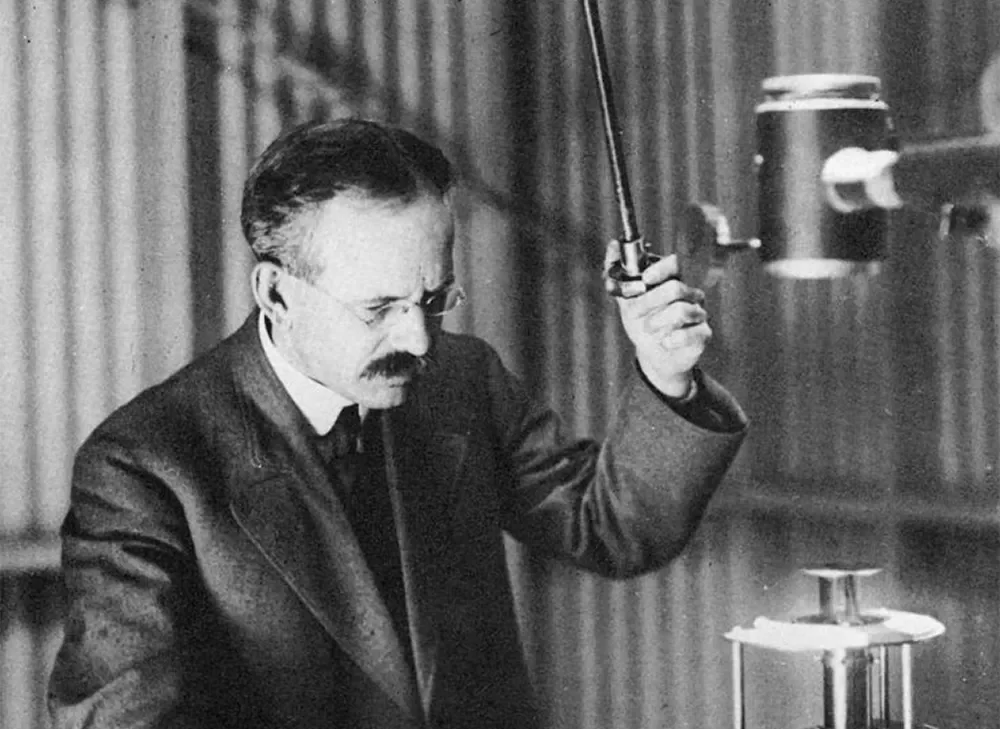

George Ellery Hale (1868-1938)

This American solar astronomer was the greatest telescope builder of the 20th century. In 1892 he established the Yerkes Observatory for the University of Chicago, together with its 40-inch refractor – which still holds the title of the world’s largest.

He founded the Mount Wilson Observatory, California, which he equipped with the 60-inch and 100-inch reflectors. Hale was also the mastermind behind the 200-inch Palomar telescope which bears his name.

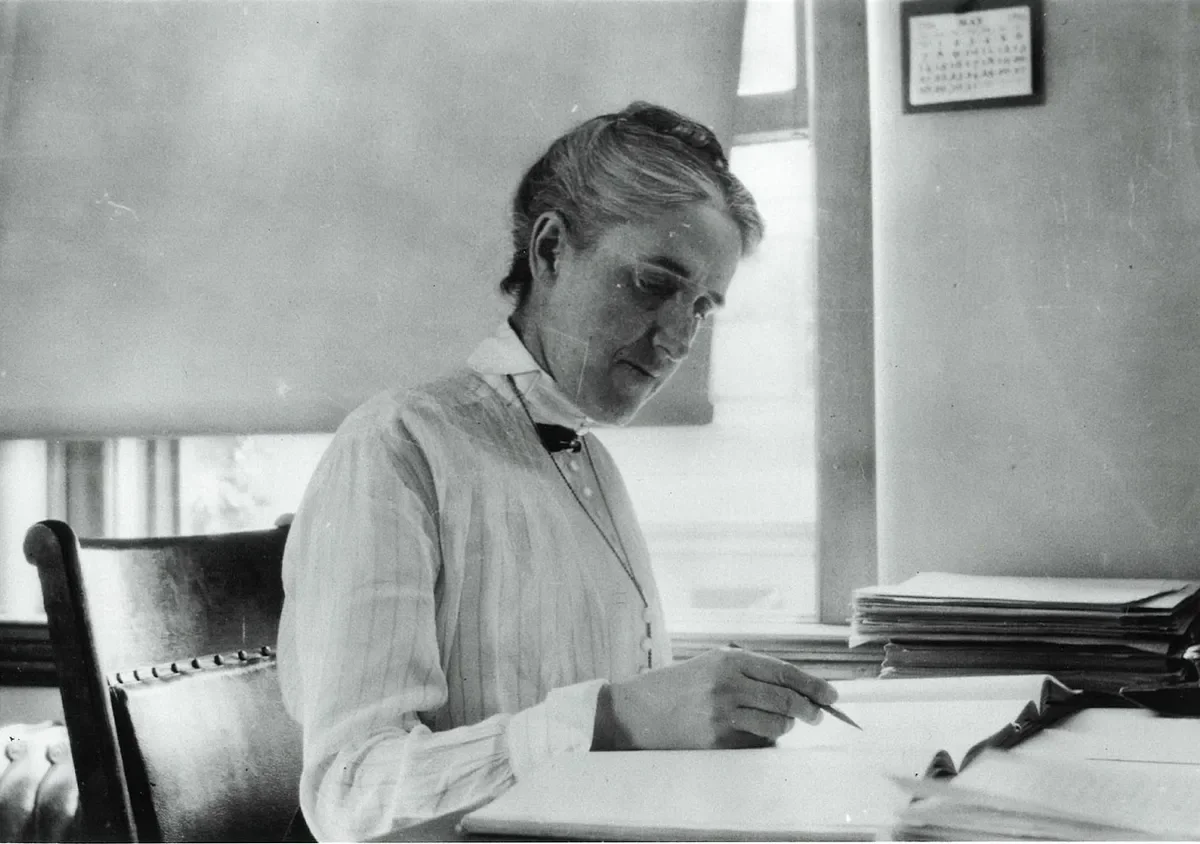

Henrietta Leavitt (1868–1921)

Leavitt found the key to unlock the scale of the Universe. In 1895 she joined Harvard College Observatory, where she measured the brightness (magnitude) of stars by studying its collection of photographic plates. Through this she discovered about 2,400 variable stars.

She noticed that the period of variability of a so-called Cepheid variable indicates its absolute magnitude, from which its distance can be estimated. This provided the first calculation of distances to galaxies.

Ejnar Hertzsprung (1873–1967)

Hertzsprung discovered the two main groupings of stars – the luminous giants and supergiants, and the dwarfs now known as main sequence stars. Henry Norris Russell made the same discovery independently.

Both created diagrams to show the groupings of these stars, which are known today as Hertzsprung-Russell diagrams. Hertzsprung also measured the distances to several variable stars, which he then used as a measuring stick to find the distance of the Small Magellanic Cloud.

Arthur Eddington (1882-1944)

In 1916 Eddington received a paper of Einstein’s general theory of relativity which explains the force of gravity using geometry. To put Einstein to the test, he observed the total eclipse of 1919 off the west coast of Africa.

His photographs displayed a tiny shift of stars observed close to the Sun, caused by the Sun’s gravity bending starlight. This observation was the first experimental confirmation of Einstein’s work, and it immediately made Eddington world famous.

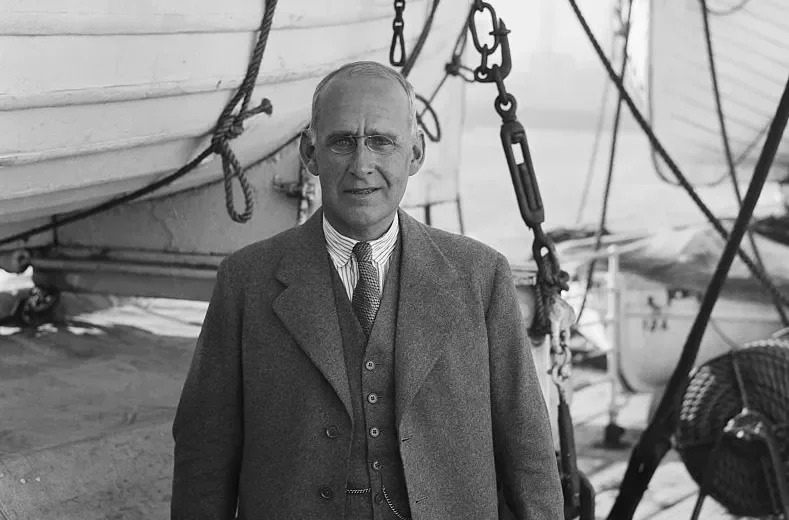

Edwin Hubble (1889–1953)

Edwin Hubble, who trained as a lawyer, was the American observational astronomer who discovered the expansion of the Universe. In 1923–24 he used the Mount Wilson 100-inch telescope to measure the distances to 18 galaxies – an enormous achievement.

When he compared these distances to redshifts measured by others, he found that a galaxy’s distance is proportional to its velocity. He thus confirmed the idea of an expanding Universe, which is fundamental to cosmology.

Walter Baade (1893-1960)

Baade made a great discovery in 1944 thanks to wartime blackout conditions in Los Angeles. He had unrestricted access to the world’s largest telescope because many staff at the Mount Wilson Observatory were dragged away on war duties.

He resolved individual stars in M31 (the Andromeda Galaxy) where he discovered that there are two distinct stellar populations of old and young stars. His finding revolutionised research on the evolution of galaxies.

Fritz Zwicky (1898–1974)

Zwicky was an astronomer who made the startling discovery that most of our Universe is invisible – filled with a substance now known as dark matter. In 1933 he examined galaxies in the Coma Cluster and discovered that they were moving too fast to remain bound within it.

Zwicky proposed the idea that mysterious, unseen matter between 10 and 100 times more abundant than visible matter, provided the additional gravitational pull needed to keep the cluster together.

Charlotte Moore Sitterly (1898–1990)

Moore Sitterly was an American solar expert and cataloguer best known for her comprehensive spectroscopic indexes of atomic spectra. Her multiplet tables became the standard reference used by astrophysicists to identify the chemical compenents of stars and are still cited today.

From 1946, she was able to make ultraviolet spectral measurements of the Sun using data from V-2 rockets and later Skylab.

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin (1900 – 1979)

Inspired by Arthur Eddington’s famous trip to observe the 1919 solar eclipse, Payne-Gaposchkin became fascinated by astronomy early on and left her native Great Britain to study at Harvard Observatory.

Carrying on the work on stellar classification of earlier Harvard astronomers like Annie Jump Cannon and Edward Pickering, Payne-Gaposchkin is most remembered for having discovered that stars are primarily composed of helium and hydrogen.

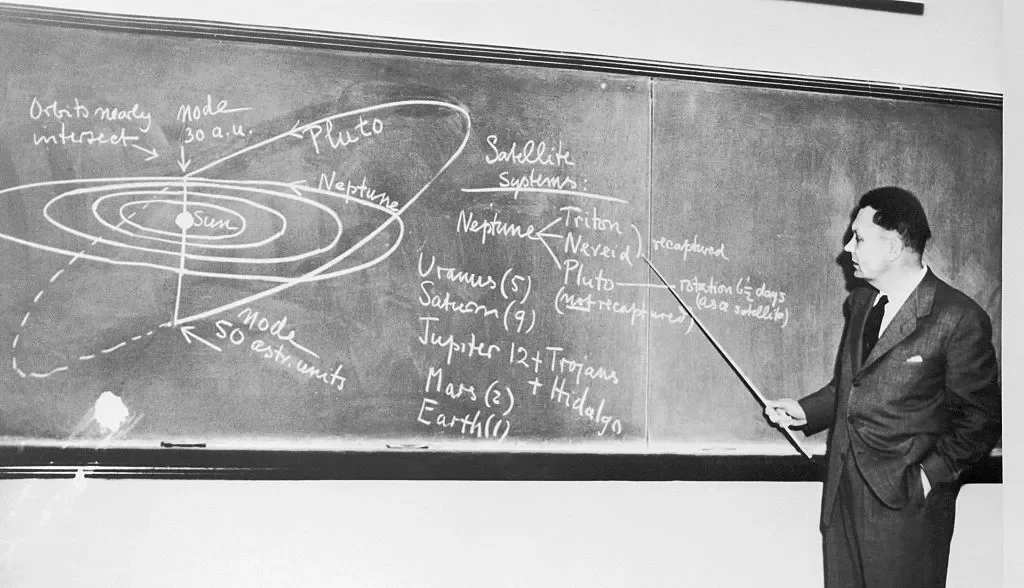

Gerard Kuiper (1905–1973)

Kuiper, the most distinguished planetary scientist of his time, discovered Uranus’s moon Miranda in 1948 and Neptune’s Nereid in 1949. A pioneer in planetary atmospheric research, he discovered the existence of a methane-laced atmosphere above Saturn’s moon Titan and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of Mars in 1944.

Kuiper is usually best remembered for his prediction of enormous swarms of comet cores and small icy bodies beyond Neptune: the Kuiper Belt.

Helen Sawyer Hogg (1905–1993)

American–Canadian Hogg published the first comprehensive catalogue of variable stars in globular clusters. Working mainly at the Dunlap Observatory in Toronto, she photographed upwards of 2,000 global clusters and discovered hundreds of new variable stars.

The program director of astronomy with the US National Science Foundation and president of the American Association of Variable Star Observers, she published over 200 papers, as well as popularising astronomy through lectures, books and a weekly newspaper column.

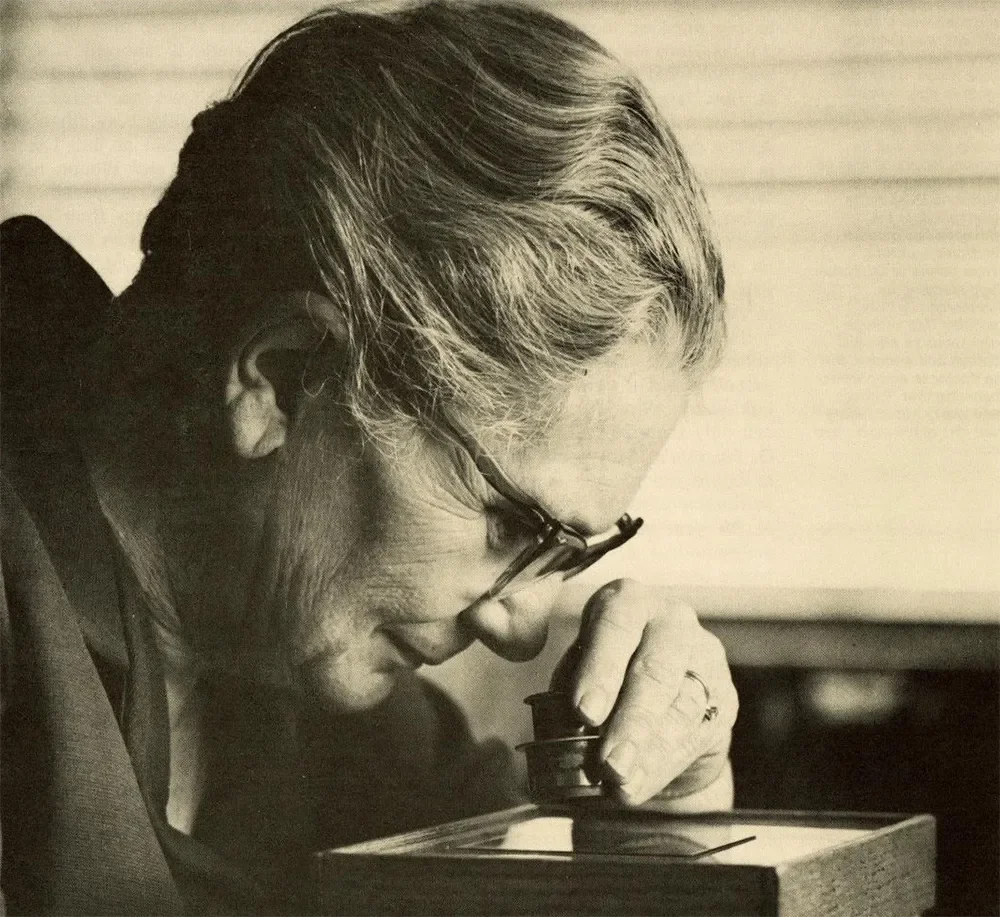

Clyde Tombaugh (1906–1997)

Clyde Tombaugh, a self-taught amateur astronomer, joined the Lowell Observatory in 1929 to work on the systematic search for a planet beyond Neptune. On 18 February 1930 he discovered Pluto when it appeared on a pair of photographic plates he had taken in January with the observatory’s 13-inch refractor.

Tombaugh doggedly pursued a time-consuming search of the ecliptic for objects beyond Neptune, discovering 14 asteroids in the process.

Bernard Lovell (1913–2012)

In 1949 Bernard Lovell set up the UK’s first radio telescope in a muddy field at Jodrell Bank, Cheshire. From this humble start he went on to make Manchester a world-class centre for radio astronomy.

At Jodrell Bank he constructed what was once the world’s largest steerable radio telescope, the 75m instrument that bears his name. Completed in 1957, it was the only telescope capable of tracking the first Soviet and American satellites – Sputnik and Explorer 1. It’s still in use today.

Martin Ryle (1918–1984)

Ryle developed revolutionary radio telescopes and receivers. While at Cambridge University in 1950 he completed the first reliable map of the sky in radio waves, discovering some 50 cosmic radio sources.

His Third Cambridge Catalogue in 1959 led directly to the discovery of quasars when optical observers identified star-like objects at Ryle’s radio positions. By the 1960s his radio surveys had superseded the steady-state theory advanced by fellow theorist Fred Hoyle.

Patrick Moore (1923 – 2012)

As the face of The Sky at Night, Patrick Moore is one of the most famous astronomers in recent history. He introduced millions of viewers to astronomy, setting a record by becoming the world’s longest-serving presenter on the same programme.

Patrick was an active member of the British Astronomical Society and one time director of sections devoted to observing Venus, Mercury and the Moon.In fact, Patrick used sketches of the Moon mad by himself and another astronomer, Percy Wilkins, to produce a large map of the Moon’s surface. The Russian space agency even requested a copy to help plan the uncrewed Lunik missions.

In 1965 Patrick took a part-time position as the director of the Armagh Planetarium in Northern Ireland.In 1995, he compiled a list deep-sky objects to complement the Messier Catalogue, known as the Caldwell Catalogue, became extremely popular.

Nancy Grace Roman (1925 –2018)

Nancy Grace Roman laid the groundwork for our understanding of how galaxies grow and founded NASA’s space astronomy programme, which has led to her being known as ‘the mother of Hubble’.

At the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory she studied the motions of stars that formed in the same cluster as the Plough, but which had drifted apart. She later expanded her research to cover Sun-like stars visible to the naked eye and noticed that where stars orbited in the Milky Way was connected to their metallicity.

At the Naval Research Laboratory she mapped out the Milky Way in new wavelengths, became head of microwave spectroscopy. In 1959 she moved to NASA as head of observational astronomy, becoming the first woman to hold an executive office at NASA an granting her overall responsibility for the agency’s space-based observatories.

Eugene Shoemaker (1928 – 1997)

Eugene ‘Gene’ Shoemaker is regarded as the founder of ‘astrogeology’.

He joined the US Geological Survey and contributed heavily to studies of data collected by the Ranger spacecraft, which impacted the Moon.

For years Shoemaker combined teaching at Caltech with astrogeological studies and took part in observational work searching for comets and near-Earth asteroids, which he undertook with his wife, Carolyn.

The pair’s best-known discovery in 1993 was that of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, which Carolyn initially described as “a squashed comet” and which hit Jupiter in 1994.

Vera Rubin (1928–2016)

American astronomer Rubin’s meticulous observations of the unusual rotation rates in galaxies provided the first direct evidence of dark matter. The theory that most of the matter in the Universe is completely invisible, developed while working at the Carnegie Institution of Washington in the 1970s, was subsequently confirmed in the following decades and revolutionised our understanding of the Universe.

Although unjustly denied the Nobel Prize, her legacy includes several prizes in her name as well as a satellite, an asteroid, a ridge on Mars, a galaxy (Rubin’s Galaxy, UGC 2885) and a major new observatory, the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile.

Maarten Schmidt (1929–2022 )

Schmidt specialised in taking the optical spectra of objects known to emit radio waves, exclusively using the 5m Hale Telescope. In 1963 he made a spectacular breakthrough when he realised that the puzzling spectrum of a star-like object at the position of one of Martin Ryle’s radio sources, 3C273, was highly redshifted.

Therefore, he deduced, it was far beyond our Galaxy. He invented the term ‘quasi-stellar object’ (that later became shortened to quasar) for these extraordinarily energetic galaxies.

Carolyn S Shoemaker (1929–2021)

Carolyn S Shoemaker was an American astronomer and one of the world’s foremost hunters of asteroids and comets.

In her lifetime she identified or co-identified over 500 asteroids and 32 comets including, with her astrogeologist husband Eugene Shoemaker and David H Levy, Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9. The fragmented comet was observed crashing spectacularly into the planet Jupiter in 1994.

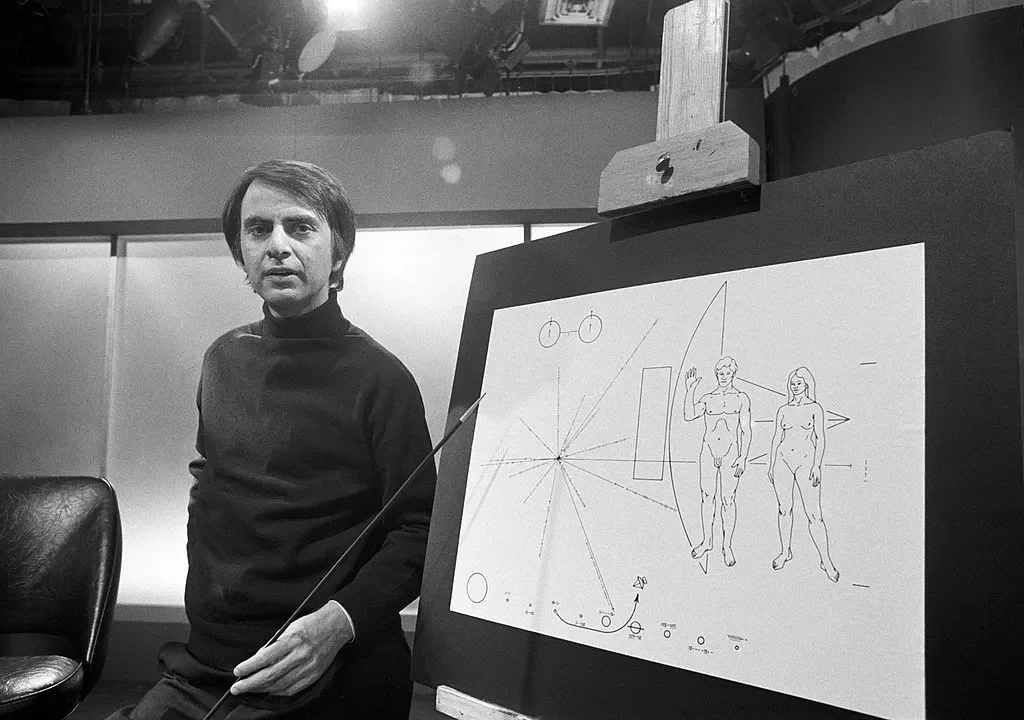

Carl Sagan (1934 – 1996)

As famous for his science communication as for his experimental results, Carl Sagan began his scientific career with a thesis on the origins of life. He would go on to create the Golden Record shot into interstellar space aboard the Voyager missions, a message to any extraterrestrial civilisations it might encounter, and briefed Apollo astronauts before their flights.

He was scientific adviser on 2001: A Space Odyssey, and cowrote and narrated the award-winning 13-part PBS television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. Sagan is easily one of the most famous astronomers in recent history.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell

Bell Burnell is credited with the discovery of radio pulsars as a student in 1967, yet the Nobel Prize associated with the breakthrough went to her PhD supervisor Antony Hewish in 1974. After this controversial start, Burnell’s career would see her appointed president of the Royal Astronomical Society from 2002-2004, and president of the Institute of Physics from 2008-2010.

She has worked as project manager for the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, professor of physics at the Open University and is currently a visiting professor of astrophysics at the University of Oxford.

Jill Tarter

A driving force in legitimising and formalising the search for life beyond our planet, American astronomer Jill Tarter is co-founder of the SETI Institute (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) and the inspiration for Jodie Foster’s character in the Carl Sagan-penned novel and film Contact.

She led the first wide-scale, targeted analysis of radio signals from space, using the National Radio Astronomy Observatory at Green Bank, West Virginia, Puerto Rico’s 300m Arecibo Observatory and the 64m Parkes radio telescope in Australia.

Linda Morabito

The Voyager missions that launched in 1977 made the first ever ‘grand tour’ of the Solar System, sending back data and images that revealed the secrets of the planets and their moons.

Linda Morabito joined the Voyager mission as an engineer in the navigation team, working as part of the team whose job it was to improve knowledge of the orbits of the moons of Jupiter, so that this could be used for the spacecraft’s optical navigation.

In the days after Voyager 1’s encounter at Jupiter she made one of Voyager’s most famous discoveries: a plume on Jupiter’s moon Io that revealed the satellite was volcanically active.

Carolyn Porco

Planetary scientist Carolyn Porco led the imaging team on the Cassini mission to Saturn and is an expert on planetary ring systems and the Saturnian moon Enceladus. Her career began on Voyager, analyzing images and making discoveries in the rings of Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, and helping to create the Pale Blue Dot image of Earth from Voyager 1.

With Cassini, Porco and her team made many discoveries at Saturn, including several new moons, new phenomena in the rings, hydrocarbon lakes and seas on Titan, as well as the geysers of Enceladus. A prediction she and collaborators made in the early 1990s, that internal oscillations within Saturn were creating particular Saturn ring features, was verified when Cassini got to Saturn, establishing the new field of planetary ring seismology.

She was the consultant on the character Ellie Arroway for the movie, Contact.

Who have we missed? Which famous astronomers should be included on our list? Let us know by emailing [email protected].