Astronomers have found the most massive stellar-mass black hole ever discovered in our galaxy — and it’s lurking “extremely close” to Earth, according to new research.

The black hole, named Gaia BH3, is 33 times more massive than our sun. Cygnus X-1, the next-biggest stellar black hole known in our galaxy, weighs only 21 solar masses. The newfound black hole is located roughly 2,000 light-years away in the constellation Aquila, making it the second-closest known black hole to Earth.

The researchers published their findings April 16 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“No one was expecting to find a high-mass black hole lurking nearby, undetected so far,” Gaia collaboration member Pasquale Panuzzo, an astronomer at the Paris Observatory, part of France’s National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), said in a statement. “This is the kind of discovery you make once in your research life.”

Related: James Webb Space Telescope discovers oldest black hole in the universe — a cosmic monster 10 million times heavier than the sun

Black holes are born from the collapse of giant stars and grow by gorging on gas, dust, stars and other black holes. Currently, known black holes fall into two categories: stellar-mass black holes, which range from a few to a few dozen times the sun’s mass; and supermassive black holes, cosmic monsters that can be anywhere from a few million to 50 billion times as massive as the sun.

Intermediate-mass black holes — which, theoretically, range from 100 to 100,000 times the sun’s mass — are the most elusive black holes in the universe. While there have been several promising candidates, no intermediate-mass black holes have been definitively confirmed to exist. By finding baby black holes and studying how they might evolve, as well as their effects on their surrounding environment, scientists hope they can fill in this cosmic blank.

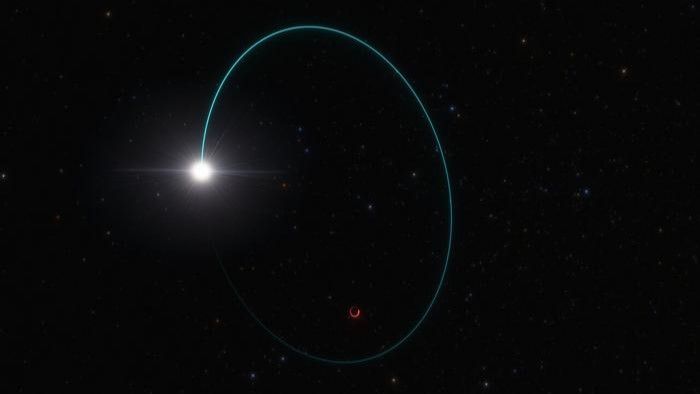

To spot the nearby black hole, the researchers used the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft, which maps the positions and movements of the Milky Way’s roughly 2 billion stars. By poring through Gaia’s data, the astronomers found one star that appeared to have a distinct wobble — a slight limp in the usually smooth path of its trajectory. The only possible cause was the tugs of an invisible companion black hole, the researchers concluded.

The astronomers followed up on Gaia’s observations with more data from the Very Large Telescope in the Atacama Desert in Chile and confirmed the existence of the black hole. The observations also helped them find a precise measurement for its mass. At 2,000 light-years from Earth, only Gaia BH1, a black hole 1,500 light-years away, is closer to us.

The researchers say they want to study it further to obtain insights into how it formed and how it might affect the matter surrounding it. Initial findings revealed that the star orbiting it is “metal poor,” or lacking in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium — adding credence to a theory that small black holes can form from stars that fused less of their nuclear fuel into heavier elements.