It was citizen assembly morning, and important matters of state were up for discussion. Therefore, one citizen dutifully made the early morning trek to the assembly. On arriving at the designated meeting space he saw… no one else. Annoyed with his fellow citizens’ disdain for the democratic process, he caustically remarked that if this were a free public comedy performance, everyone would have been present on time—even early, all in order to get the best seats.

This citizen is the fictional creation of the late fifth-century BCE Athenian comic playwright Aristophanes. And yet, jokes make the best sense when rooted in reality. What Aristophanes was mocking in this joke, itself part of a free public performance of his comedy Acharnians (425 BCE), was that in the Athenian democracy, the most democratic space of all was the free dramatic performances, the tragedies and comedies that the city put on for the benefit of all citizens at public expense. Voting or assembly meetings did not even come close to garnering similar attendance.

Before we totally condemn the Athenians as selfish, entertainment-addicted bad citizens—which, to be fair, they sometimes (or often?) were, just like us—it is worth considering what such shared democratic spaces of entertainment facilitated. And a related question to consider: What might we, as a democracy, gain if we had something similar?

I contend that the enormously popular Athenian tragic and comic performances, held at multiple festivals throughout the year, provided the Athenians with shared occasions to weep and to laugh—achieving that catharsis of emotions, of which Aristotle later wrote in his Poetics. Often these plays used mythological or other fictional storylines to comment on current events—such as Acharnians, whose protagonist, Dicaeopolis, fed up with politicians’ ineptitude, secedes from Athens, declares his little farm a kind of Switzerland, and signs a peace treaty with the Spartans with whom Athens is currently at war. In another of Aristophanes’ comedies, Peace, a different Athenian farmer protagonist, Trygaeus, dramatically fattens up a dung beetle (just imagine the high quality of humor involved in that opening scene!), all to be able to fly up to the sky to petition the gods for peace.

In tragedies, on the other hand, we encounter commentary on everything that could go wrong in a man’s life—an expression of shared fears and opportunity for shared mourning. Consider Oedipus, whose story inspired multiple tragedies by different playwrights. What if the gods are angry at a man and, even, his city, all because of a curse that he knew nothing about? And yet, at the same time, Athenian tragedies were fiercely patriotic, as they showed most of the worst disasters that could befall someone happening in other city-states. Resolutions to the worst tragedies imaginable, by contrast, could be found in Athens, the proud giver of justice for all the Greeks.

We might consider, for instance, the mythical protagonist of Aeschylus’ trilogy Oresteia. Persecuted by the Furies, goddesses of revenge, for killing his mother—which he was ordered by the gods to do to avenge his mother’s murder of his father (and you thought your family was dysfunctional?)—Orestes finally finds justice in Athens. Oedipus too, blind at his own hands after learning of his family’s curse and his own role in perpetuating it, ultimately ends up in Athens in Sophocles’ tragedy Oedipus at Colonus. Colonus, a village on the edge of Attica, the farming region surrounding Athens and belonging to it, becomes Oedipus’ final resting place. Athens, again, is portrayed as the welcoming home for refugees, the unfortunate ones persecuted by men and gods alike. And then there is Euripides’ Medea, the wronged common-law wife of the Greek hero Jason and the protagonist of the tragedy Medea. When Jason abandoned her to secure a better marriage, she orchestrated the deaths of his new bride and that bride’s father, then killed her children with Jason. At the end of the play, she acts as her own dea ex machina, dramatically escaping in a dragon-drawn chariot, bound for Athens, where she too, like Orestes and Oedipus, will find a safe haven and a place to mourn all she has lost.

For the citizens of the Classical Athenian democracy, such plot lines offered an occasion to be proud of their city. Also, they provided an escape from their mundane farming or trading life and gave them shared stories to consider together. Citizens, we can be sure, not only attended plays together but also continued to talk about them for weeks and months after. Jokes from comedies likely entered popular language, whereas tragic storylines inspired reflection, mourning, and even fear: could my own wife turn into a Medea? The poetic format of these plays, furthermore, made it possible to memorize long chunks wholesale—just as we can recall many songs from memory, regardless of whether we tried to learn them or not (here’s looking at you, “Baby Shark”), but must work much harder to memorize a famous speech in prose.

In other words, the stories that the Athenian citizens saw on stage provided a common literary canon for the democracy—a shared body of treasured texts and stories for people who otherwise could agree on virtually nothing else.

It is difficult to overestimate the significance of such a shared on-going and growing literary canon for a city-state whose citizens held incredibly diverse political views—ranging from the most progressive “power to the people” demagogues like Cleon, to the most conservative oligarchs who opposed the very existence of a democratic form of government. I believe that this diversity of political views, united in discussions of shared narratives, offers a significant lesson for us as well.

If nothing else, the recent book bans and general wars over books show the fracture of American democracy particularly clearly. As historian Mark Noll has argued, for much of American history, the Bible truly was “America’s book,” the one work of literature with which everyone was well-versed, even if reading it often quite differently. But the Bible is now too contentious in the eyes of America’s pluralistic and secularizing culture to have this unifying role. Instead, in today’s climate, there is no shared book or books that all can agree to read or listen together and to value as essential for promoting peaceful and productive conversations among people with otherwise widely differing views whether in public or private spheres. We are the poorer for it.

Shared canons now mostly exist in silos. Read by members of “in groups” alone, these shared readings too often serve to further isolate rather than to encourage public conversations across the aisle. Yet glimpses of the success of shared readings in such programs as University of Wisconsin’s “Go Big Read” still exist on a small scale and give a glimpse of what we could have on a larger scale.

Indeed, the very act of reading—and the study of the humanities and the liberal arts to which reading is foundational—is falling out of fashion with educational leaders and administrators, as the cuts to the humanities in higher education keep coming. So what is left?

We are left. The citizens who still read and delight in literature. The publications that still offer shared platforms for writers and readers who disagree over so much, including politics, but who still hold this in common: that for a democracy to stand, citizens must continue to discuss ideas together, and reading books about these ideas with our fellow citizens across political and economic and social and racial lines might enrage and befuddle us, but it at least keeps us talking with one another. That is no insignificant thing.

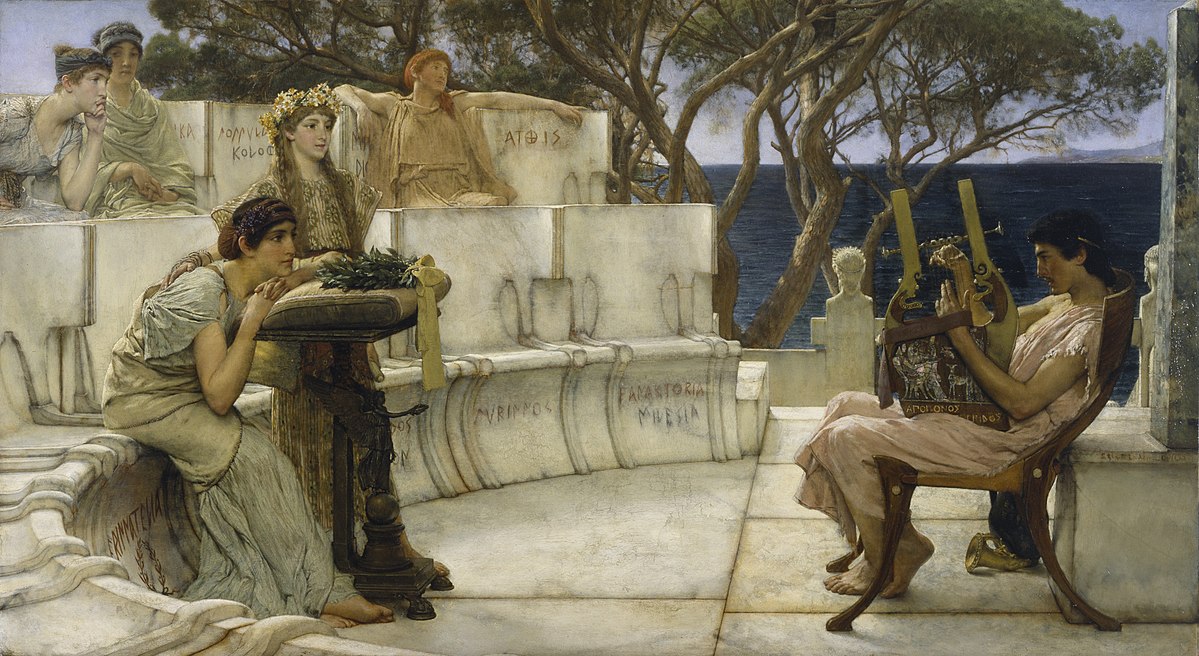

Image credit: Sapho and Alcaeus via Wikimedia Commons