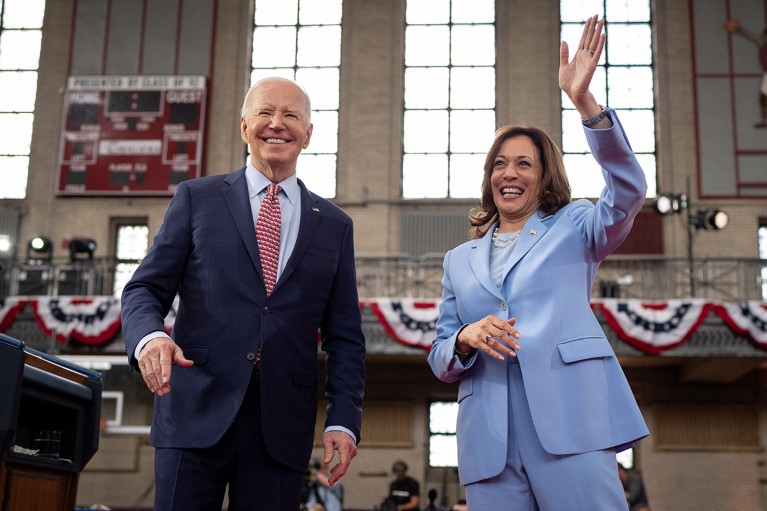

President Biden has endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris to take his place in the November election.Credit: Andrew Harnik/Getty

After US president Joe Biden ended his re-election campaign on Sunday, he and other senior Democratic politicians threw their support behind vice-president Kamala Harris. Although the situation could change between now and the official selection of the Democratic candidate for the presidency in August, she is widely expected to face off against former president Donald Trump this November.

Here, Nature talks to policy analysts and researchers about what a potential Harris administration might mean for science, health and the environment.

A background in science and justice

Health and science have been a part of Harris’s life since an early age: her mother, Shyamala Gopalan, who Harris cites as a major influence, was a leading breast-cancer researcher who died of cancer.

Much of Harris’s career has centered on criminal justice – she served as the district attorney for San Francisco for seven years and then California’s attorney general for six years until 2017 when she was elected as a US senator for the state.

As senator, Harris co-sponsored efforts to improve the diversity of the science, technology, engineering and medicine (STEM) workforce. She introduced legislation to aid students from underrepresented populations to obtain jobs and work experience in STEM fields. And as a candidate in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, she proposed a plan to invest $60 billion to fund historically Black universities and bolster Black-owned businesses.

As vice-president, Harris has overseen the National Space Council, which is charged with advising the president on US space policy and strategy. Under Harris’s leadership, the body has focused on international cooperation, for example on the Artemis mission, which aims to send astronauts to the Moon.

It is still unclear who Harris will choose to be her running mate if she receives the party nomination. One contender is Mark Kelly, an Arizona Senator and former astronaut, who would bring his decades of experience in science and engineering to the position if chosen.

Healthcare and drug pricing

During the 2020 Democratic primary race, Harris was to Biden’s left on healthcare policy. For one, she endorsed a universal single-payer national health insurance system — which still included a role for private insurance companies — while Biden preferred tweaking the existing system, which he had helped to engineer as vice-president.

It is still unknown whether she will embrace these kinds of progressive health policies or choose a path that might be more appealing to independent and centrist voters, says Alina Salganicoff, director for women’s health policy at the health-policy research organization KFF, based in San Francisco, California. “I anticipate she’s going to be a staunch defender of maintaining and supporting the Affordable Care Act, which has also been a priority for the Biden campaign,” she says.

The Biden-Harris administration has also made drug pricing a key priority by creating a cap for the price of insulin and by endorsing the use of ‘march-in rights’, in which the government could intervene to set the price of innovations created using public funds. In 2019, Harris co-sponsored legislation that would have created an independent agency to determine appropriate drug prices.

Peter Maybarduk, director of the access to medicines programme at the advocacy organization Public Citizen, based in Washington DC, praised these actions, and said he hoped they would continue under a potential Harris administration, “The Biden-Harris administration has been by far the strongest yet in challenging outrageous drug prices and starting the country down a long road toward medicine affordability,” he says.

Women’s health

Harris has been more vocal than Biden on abortion rights. Last December, she launched a nationwide reproductive freedoms tour, in which she became the first US vice-president to ever visit an abortion provider.

This has been a major issue for voters in the US, with 63% of the population saying that abortion should be legal in all or most cases according to a poll by the Pew Research Center in Washington DC. Support for abortion rights, after they were dramatically curtailed by the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision in 2022, is thought to have fueled important Democratic wins in the past year. “The fact that she’s willing to talk about this is going to be enormous, because that’s a winning issue for Democrats,” says Melissa Murray, an expert in reproductive rights at New York University, in New York City. “It’s a major point of differentiation between the two parties and the person who can make that case most clearly to the American public, I think will be in a stronger position.”

Harris’s approach to reproductive justice is not limited to access to contraception and abortion, Murray notes. The vice-president has advocated for maternal health issues more broadly, highlighting the need to combat implicit bias against black women in healthcare. This approach “takes seriously the needs of women of color, who are perhaps more deeply affected by assaults on reproductive freedom, as we’ve seen in the two years since Dobbs,” Murray says.

Climate and environment

Harris has long promoted action on climate as well as environmental justice, says Leah Stokes, a climate-policy researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara. As a district attorney in San Francisco and then attorney general for the state of California, Harris became a champion for communities on the front lines of fossil fuel pollution, Stokes says. Harris followed a similar path with work on public health and the environment as a senator from 2017-2021.

If she prevails in November, Harris is expected to maintain both the momentum and the unprecedented investments that Biden has injected into the climate movement in the United States. This includes upwards of US$1 trillion in funding for clean energy and climate change over a decade, a legislative accomplishment that many energy experts say could sharply reduce US greenhouse gas emissions over the coming decades.

“Harris and Biden are in lockstep on climate, and that’s exactly what we need,” says Stokes. “Our 2030 goals are right around the corner, and we can’t afford to roll back progress for four more years.”