In July, researchers in the United Kingdom published a code of practice on how human stem cells should be used to mimic embryo development in the laboratory. This code was produced by a working committee of 13 developmental biologists, stem-cell scientists, legal scholars, regulatory specialists and bioethicists, of which I was chair. It is the first of its kind in the world.

Such guidelines are sorely needed, because of the similarities between human embryo models and natural embryos. Some countries, including Australia and the Netherlands, have proposed that these models should be regulated by the same laws that restrict research on human embryos. But in the United Kingdom — as well as in the United States, France and other countries — embryo models remain legally, as well as biologically, distinct from natural embryos.

Lab-grown embryo models: UK unveils first ever rules to guide research

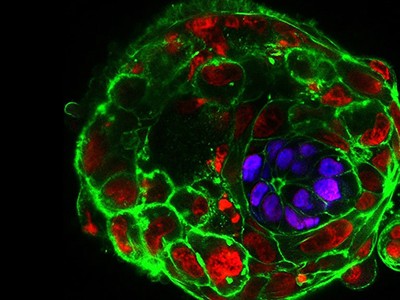

Grown from stem cells in the lab, human embryo models are 3D structures that mimic various aspects of the first weeks of human development, allowing researchers to study early events in pregnancy and miscarriage, and to analyse how drugs and toxins might affect growth. Over the past ten years, researchers have found ways to replicate human development more closely and design embryo models more effectively. But this progress has led to concerns in the media and among the public that stem-cell-based embryo models might one day be used to create a viable organism, raising ethical issues.

We designed our code of practice to reassure the public that UK research on stem-cell-based embryo models is being conducted ethically and transparently, and to ensure that scientists know what they can — and cannot — do with these models. For instance, the code prohibits researchers from transferring a human embryo model into a person’s uterus to attempt to establish a pregnancy. It also dictates that no researcher can generate or use a model without approval from an oversight committee of UK scientists, lawyers, bioethicists and members of the public. The committee, to be chosen by a process that is yet to be determined, will be set up by the end of the year.

Some researchers have questioned whether the guidelines should align more closely with existing laws regarding human-embryo research. Many laws dictate that natural human embryos cannot be cultured past 14 days — just before a structure called the primitive streak forms, marking the beginnings of the embryo’s head–tail axis. By contrast, our guidelines do not explicitly state how long each embryo model can be kept in culture. Moreover, the code doesn’t refer to any developmental ‘red lines’ akin to the primitive streak. And the guidelines, although recommended, are not legally binding. But, by avoiding writing oversimplified limits into law, we can ensure that the code of practice is fit for purpose for years to come.

Most advanced synthetic human embryo models yet spark controversy

It’s impractical to apply unified limits to all types of embryo model. Natural embryos all develop in much the same way, at much the same tempo, whereas stem-cell-based embryo models come in many shapes and sizes, each starting and ending at the equivalent of a different developmental stage. It’s hard to specify a single point for all models at which research should cease.

Instead, our code stipulates that scientists should define and justify the endpoint of the models they intend to use to the oversight committee, and culture them for the shortest time possible to answer their research question. Decisions on the appropriate limits will be made by the oversight committee on a case-by-case basis, taking into consideration the embryonic features under investigation, the scientific value of the research and whether the questions can be addressed using alternative models.

For example, a researcher using a model that lacks the cells needed to form the placenta — without which an embryo is not viable — might be allowed to continue their experiment even after a structure resembling the primitive streak forms. Someone using a model that contains these cells might not.

Perhaps the most controversial embryo models are those that mimic aspects of human-embryo development during the week after the primitive streak has formed. These models are the only available tool that can visualize this stage of development. So far, researchers have ended experiments at a time equivalent to day 14, rather than seeing how long they could develop the models. Under our code, all proposed endpoints must have a valid scientific purpose. Seeing how far models will develop is insufficient.

I understand people’s urge to legislate on research related to human development. But changing legislation can take time. The code of practice can be reviewed and revised as needed — this is crucial in allowing progress in a rapidly changing field. Because the guidelines reflect the public’s voice and have had input from a wide range of stakeholders, I’m confident that UK researchers and institutions will follow them. In other countries, different ethical, legal and scientific considerations might call for another approach.

Although the code is designed for the United Kingdom, people elsewhere might find it helpful, and aspects of it could be used in designing guidelines for other jurisdictions. Shared principles in such a cutting-edge field help to foster public trust. I hope that researchers in the United Kingdom and beyond see the merit of our effort.