While mysteries can usually be trusted to compel the reader within the first chapter or even the first few pages, it’s rare for them to hook us from the first paragraph. But West Heart Kill, Dann McDorman’s clever debut, achieves this with intriguing tongue-in-cheek confidence.

The book opens with the protagonist, detective Adam McAnnis, sitting in the passenger seat of his old friend’s car on the way to the exclusive West Heart club in upstate New York, to celebrate the Bicentennial. There, a body is found at the lake’s edge just as a major storm closes in, preventing exit. Sex, booze, and drugs abound, as do ulterior motives, and over the holiday weekend, most characters will prove not to be who they seem.

West Heart Kill unfolds like a traditional mystery while at the same time flipping every genre trope on its head with self-reflexive mischief. McDorman plays with structure, narration, and characterization, subversively engaging his readers to question their love of stories that, at their root, celebrate violence and death. This could cross the line into condemnation if the author weren’t himself so clearly enamored with the mystery genre, offering instead a delightful spin on the form.

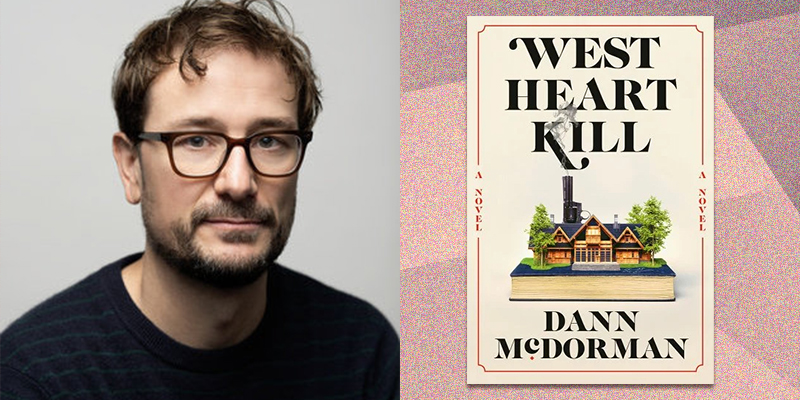

Dann McDorman lives in Brooklyn, New York, with his wife and two children. Alongside writing novels, he is an Emmy-nominated television news producer. He spoke with CrimeReads about West Heart Kill, his love for the mystery genre, and the fun he had thinking and writing outside the box for this first book.

Jenny Bartoy: West Heart Kill is both a solid whodunit and a meta satire of the genre. It’s also your debut. Tell me a little bit about where the idea for this book came from.

Dann McDorman: I’ve wanted to be a writer my whole life, and I tried very hard through my twenties. Then sometime around 30 I was like, I either lack the talent or the discipline or both to do this. I gave up and developed my career, raised my kids, buried my parents, all that grown-up shit. And then two summers ago, on a whim, I wrote the imaginary dust-jacket copy for a book that didn’t exist. And it had a detective and a setting and promised all these plot twists and shocking secrets, none of which I’d invented yet. And I showed it to my wife and said, “Maybe I should try to write this,” and she said, “You should.” And that was sort of how the book began. I didn’t have any clue. In the beginning, I thought I was just writing a standard murder mystery. And almost immediately I fell into this “you” voice addressing the imaginary reader. Once I was in that space, then it was open season. I could do any kind of crazy stuff that popped into my head.

JB: You play with form and technique quite a bit: the point of view changes; you include mini essays about philosophy and etymology, and case studies about the mystery genre; there’s a questionnaire and word problems and other playful elements I don’t want to spoil for anybody. This book kept surprising me and I couldn’t wait to see what would be around the corner. I’m curious what came first once you started really writing the book: story or form?

DM: In terms of plot, the only thing I had at first was that, on a wall of the club full of plaques of past presidents, there would be one missing—but I had no idea why. And a lot of the conventional murder plot was me trying to answer that question for myself because I liked that idea. So it was a little bit of a tail wagging the dog. I think what hopefully sets the book apart is all the other shenanigans going on. It was already weird because of this unusual second-person voice. Then the first breakout thing was the dramatis personae. I knew I wanted to include it because of classic murder mysteries. Every Agatha Christie book has this character list, it’s great. But I struggled with it because I needed to withhold key facts about each character for good reason, because otherwise there’s no reason to finish the book. I decided to write the full truth about every character, including who’s related to whom and who is secretly doing what to whom, who dies, who the murderer is, and put it all in there for real but then cover it with a censor bar, like it was redacted by the CIA. That became a theme for the whole book, where what’s usually in the background gets moved to the foreground.

So that was the first weird thing, then the next idea I had was the word problems. Which seemed like too good an idea not to do! So I said, well, if I write a whole novel, and there’s just these two odd things in it, that’s kind of strange, so maybe I’ll just put in a lot more of this kind of thing, and turn the bug into a feature. At that time, I’d been doing a ton of research into the genre because I was a big fan obviously, but didn’t know if I was qualified to write a mystery, and I found it all fascinating. And I thought maybe the reader will think it’s fascinating too. So I started writing these little breakout essays and interstitials to punctuate the book. And what got really exciting was that the story and these essays started playing off each other. Writing the essays would give me an idea for something to do in the plot. And sometimes I’d write an essay and then 100 pages later do what it explains, or something happened in the plot, and then 100 pages later, there’d be an essay that helps explain it. So everything became very enmeshed. Of course I did a bunch of retroactively configuring things, but it was pretty organic. The book now is fairly complex. But it’s not like I had some epiphany on day one. It wasn’t like that at all.

JB: While speaking directly to the reader is not unheard of in mystery, you deliberately break the fourth wall in a way that feels subversive. From the first page, the reader is an active part of the story, and this makes them feel both engaged and a little squirmy. They have to assess their fascination with a violent genre, even as they’re actively enjoying it. This narrative approach reminded me a little of Dungeons & Dragons or Choose Your Own Adventure, but with a twinge of compunction like being questioned on the stand. What were your intentions with weaving in the “you” and did things change as you wrote?

DM: I wish I could say that it was some well-thought out thing, but like I said, it was almost instantaneous. The first paragraph in the book is the first version I wrote, so the “you” was there from the beginning. Maybe it was just instinct or whatever I had for breakfast that day, but that was how it started. And obviously there are famous books and even recent literature written in the “you” voice—Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney; Carlos Fuentes has a great novella called Aura; and there are others. Italo Calvino has a book called If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, where he does something very similar although it’s not a mystery. I didn’t consciously think about it when I started but certainly, at some point I went, a lot of this is Calvino’s influence. A lot of the magic in the book is this sense that it is being written before your very eyes, it’s unfolding as you read it. It’s like you’re peeking over the writer’s shoulder; you’re seeing it as it happens. And it would have been a little exhausting if my entire book had been written that way, but there are a lot of other perspectives.

JB: Let’s talk about this variety in narrative point of view. In the novel, you switch around quite a bit from the “you” to the first person to third-person close POV to the collective “we.” The narrator even explains these shifts in psychological terms, which is both fascinating and hilarious. Can you tell me a little bit about your decision to shift POVs?

DM: That came pretty early on, before any of the other weird shenanigans were conceived. I decided to do each day in a different perspective, just to give each day a little bit of a stamp that sets it apart. So the “I” on Friday, then “we” on Saturday, returning back to the third person on Sunday. Once all the other complexities started going in, I was like, oh my god, this is getting unwieldy. But in the end, I’m very happy I did it. I thought diving into the mind of the detective followed by the “we” on the next day was good because you essentially have a whole setup and then you learn more about him. In the “we” consciousness I was able to disguise the identity of the murderer which felt kind of cruel to do to the reader but also kind of fun. But the “you” is underneath everything; we keep returning to it throughout.

JB: You weave in quite a bit of research from the Greek philosophers, to parables from the Bible, to extensive details about a variety of mystery writers, particularly Agatha Christie. How much research went into the writing of this novel?

DM: I knew a great deal about a few writers: Agatha Christie, Conan Doyle, G.K. Chesterton, Paul Auster. But I wanted to get a wider exposure. I was in the basement of The Strand in Manhattan, and I turned a corner and there was this big thick volume, the Oxford Companion to Crime & Mystery Writing. That was very useful. I knew in advance certain things I wanted to do — for example, talk about the use of alibis among mystery writers, which is very common — and I had everything except the actual facts. So this encyclopedia helped me to fill in the blanks. The thing about mysteries is you can read most of them pretty fast. So I tore through a bunch of those. I hadn’t read certain classics, but I thought I’d better read various versions of the “Locked Room,” for example. So a lot of my research was primary sources like literally just reading these original books. And then some of it was researching these secondary sources like the encyclopedia or Julian Symons’s book, Bloody Murder. It’s the best study of the genre.

But you have to be very careful what you’re reading when you’re writing! A few years ago I had gotten this new edition of the Hebrew Bible translated by the scholar Robert Alter. I’m not Jewish, but it’s full of footnotes, which is fascinating. So, I’ve been reading parts of that off and on for years, and I just happened to be reading the David story at some point. And in pops one character telling you a story about David and Bathsheba in a way that’s relevant to the novel. So you gotta be careful because there’s stuff that may get in without you meaning to.

JB: West Heart Kill is set in the 1970s and there too you include a lot of research: fantastic sensory and contextual details, countless brand names, and then so much sex and pot smoking! Why did you set the story in that time period?

DM: It was kind of fun, but I also wanted something that was a little bit in the past. Setting the story before cell phones and the internet simplifies things for a mystery writer. The highfalutin answer is that the zeitgeist of that era, in many ways, feels similar to now. There’s this feeling of fear that things are getting worse, not better. This sort of ambient anxiety that institutions are crumbling and not working anymore. It felt very relevant as I wrote it. And then some of the most fun I had was looking at clothing catalogs from that time period, which led directly to an early paragraph which is entirely brand names of all the artificial fabrics of the era and which I obsessed over. So it was fun in that way, but it felt right too. I wanted the detective to be a little bit broken, and Vietnam seemed a natural thing. I’m an army brat and I come from a line of people in the army. My grandfather was in both Korea and Vietnam and, growing up as a kid, I saw firsthand how messed up he was. So I drew a lot from those memories for that aspect of the detective character.

JB: Speaking of character development, I love your attention to women in this novel. Men have often been mocked and memed for not knowing how to write women, but I thought your female characters were strong, complex, and relatable. And you also make a point throughout to discuss the problematic treatment of women in the mystery genre historically, but also culturally and in terms of violence. You touch on postpartum depression, suicidal depression, and domestic abuse — which feels both heavy and believable. Was this important to you?

DM: It was, yes, partly because women are often the victims in murder mysteries. But crafting the plot and the characters was the hardest part for me. To try to get some of the tone right — I am a middle-aged man, you know — I read a lot of women writing in that time, like Renata Adler, Joan Didion, Elizabeth Hardwick. The 1970s felt like a very interesting and complex moment for women: post-Pill, post-sexual liberation, but from what I could tell in the GQ and Esquire from that era, men were using this newfound liberation as just another way to exploit women. That felt interesting. And I was interested in the difference between a young woman in this time and someone in her late forties, who basically was already grown up and probably had kids before things got “fun” but was too old to start fresh. So that dynamic played out a little bit in some of those characters. I think the four main women characters in the book are all deeply sad.

JB: Yes, I agree. They all seem unsettled. You also bring up politics in this novel, which is not completely unusual, but a lot of mysteries eschew politics. So it’s potentially risky territory. In particular, you write about antisemitism. One character is Jewish in a very white, conservative, and exclusive setting. Tell me about this thematic choice.

DM: Part of it is just a desire to have some realism because any place like this club in that time period would have been super Waspy. If they’re wealthy, they tend to be conservative. And at that time there would almost certainly have been a “no Jews allowed” policy or some such unwritten rule. So I thought that was just part of the fabric of this type of wealthy club. It also was a time when conservatism was ascendant. So when one character describes whatever’s covered in her copy of Esquire, that’s what was in it at the time: William F. Buckley, G. Gordon Liddy. That was the writing of the time so it became part of the texture and the fabric of the environment. As I got into the time period more, I thought the stranger applying for club admission being Jewish would add an interesting tension.

JB: Which I think it did, for sure. I feel like I could discuss and dissect this book for hours! But that’s it for my questions about West Heart Kill. I heard that you already have a deal with Knopf for a second book. Congratulations! Is that going to be a mystery as well?

DM: It’s not a mystery, but it’s mysterious, if that makes sense. I use some of the tricks and techniques of a mystery novel to tell a different kind of story. But it’s got a lot of the same meta stuff—I think this is what kind of writer I am. If you liked the meta stuff in West Heart Kill, and some of the hijinks that go on in the literary sense, there’s a lot of that in the second book too. I’m a sucker for literary novels that are very meta and have an innovative structure, whether it’s Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov or Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell. There’s a book by Philip Roth called The Counterlife in which each part is very different and it sort of pulls the rug out from under you and what you thought the part before was about – it’s great. So I wrote the kind of book that I like. And I hope people like it. I hope that people who like mysteries like it, but also people who like highfalutin literary shenanigans!