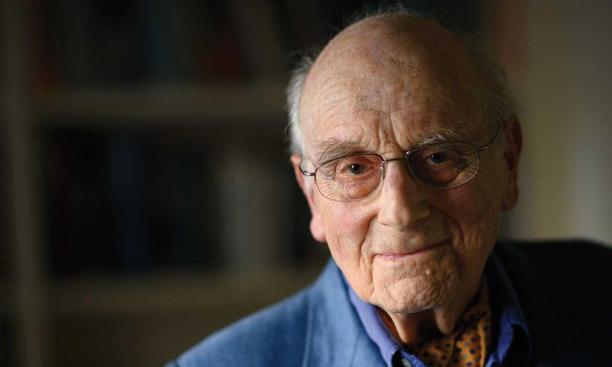

Victor Brombert

The book: A celebration of the lifelong literary career of Victor Brombert, The Pensive Citadel (University of Chicago Press) offers a variety of reflections from the beloved emeritus Princeton professor. A scholar of 19th and 20th century French literature, Brombert’s collection of essays touches on both his personal experience and the impact of various works of literature. Essay titles include The Permanent Sabbatical, The Paradox of Laughter, and Cleopatra at Yale. The book includes a foreword by Christy Wampole, an assistant professor of French at Princeton. In her final reflections she writes, “Brombert shares his vulnerability with faceless readers, a final gesture of benevolence.”

The author: Victor Brombert is the Henry Putnam University Professor Emeritus of Romance and Comparative Literature at Princeton University where he taught from 1975 to 1999. He is a scholar of 19th and 20th century French literature and is the author and editor of more than 15 books, including The Criticism of T.S. Eliot and Memories of a Stateless Youth.

Excerpt:

Chapter 14 – The Year of the Eiffel Tower

1889 was the year when France commemorated the centennial of the Revolution. In that year, the apotheosis of Victor Hugo, high priest of democratic virtues, whose remains an entire population had accompanied to the Pantheon, was still a fresh memory. Hugo’s life (1802–1885) and work almost literally filled the century, and it was the century he had come to embody that was now being celebrated.

The festive commemoration of the fall of the Bastille was meant to glorify the nineteenth century as an age of progress. It was a century that began under the shadow of the Revolution, and that repeatedly revived revolutionary dreams and fervor. It had, however, also turned out to be a century of discontinuities, counterrevolutions, and repression. 1815, the year of Waterloo, can be viewed as pivotal, an end of a regime, but also a new beginning—and so were 1830, 1848, and 1870, all of them dramatic dates that marked a forward thrust, as well as a regression and relapse into the past. But in 1889, the Third Republic, the régime in power, could claim that it was the undisputed heir to the principles of 1789.

The Eiffel Tower, the outstanding monument of the Exposition Universelle, was 1889’s answer to the razed Bastille. Its erection monumentalized the achievements of the century, even though some ironically inclined minds complained about its gigantic funnel-shaped form and the architect’s obscene delusions of grandeur. For most, however, the three-hundred-meter-high steel architecture became the appropriate symbol of the historic occasion. In that year of the Exposition Universelle, there was an all-pervasive display of the out-sized: allegorical ceremonies, immense exhibits, dazzling illuminations, solemn inaugurations (the great amphitheater of the Sorbonne, among others), massive parades. On August 18, more than fifteen thousand mayors of metropolitan France and overseas territories paraded in ceremonial garb. The centennial also consecrated the preeminence of Paris, capital and heart of the nation. More than that: it was glorifying Paris, in Walter Benjamin’s famous phrasing, as the capital of the nineteenth century.

Neither Paris, nor France, were single-voiced in their appraisal of the republican mystique. During the last three decades of the nineteenth century, the principles of the Third Republic (which lasted until the French defeat of 1940) rested on the ideological pillars of anticlerical laïcité (or secularism), combative optimism, financial opportunism, parliamentary factions, and chauvinistic patriotic poses. This complex republican ideology, however, did not go unchallenged. Frontal attacks on the scientific spirit, as well as on the intellectuals in general, coincided with the euphoric celebrations of the centennial. These attacks were not new. As early as the 1840s, various pamphlets and books, largely encouraged by a sectarian Catholic press, had denounced the pernicious influence of professors on France’s youth. The last two decades of the nineteenth century witnessed a major offensive against the intellectual establishment. Paul Bourget’s central thesis in his widely read novel, Le Disciple, which appeared in 1889—the very year of the Eiffel Tower—was that teachers, associated with the central tenets of scientism and democracy, should be held directly responsible for the moral effects of their dangerous philosophy on their students.

In the wake of the humiliating defeat of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, followed by the trauma of the Commune, Bourget and his followers sought salvation in traditionalism and intransigent nationalism, denouncing intellectuals as subverters of conservative values. Many of the anti-intellectual pronouncements of the late 1880s, and beyond, condemned the academic elites as a new class of mandarins who considered themselves as the spiritual guides of a democracy that came to be known as “la république des professeurs”—academics who, with their ideological teachings, had corrupted an impressionable younger generation, thus sapping France’s finest traditions. The real target of these attacks was of course the democratic mystique itself, and beyond that, the tenets of the Revolution held responsible for all the contemporary social and moral ills.

But critical assessments of the legacy of the Revolution also found their way into the writings of the decried intellectual masters. Hippolyte Taine’s Les origines de la France contemporaine (1875–93) was hostile to the revolutionary leaders, naming Danton a “political butcher” and Robespierre “the ultimate runt.” Even Ernest Renan, though he considered the Revolution as the “sublime” French epic, in the final analysis came to judge it a failure (“une expérience manquée”), and even an “odious and horrible” event that in its consequences bureaucratized France, leaving it a spiritual desert where only material prosperity is valued.

The commemorative festivities of 1889 were hardly necessary to remind the French of their revolutionary past and its consequences. Many surely preferred to forget the most violent features, but these could not possibly be forgotten. Nor could the Revolution be considered a closed chapter. Its mission or ideals had never really been fulfilled. The history of the nineteenth century had been afflicted by a series of dramatic caesuras, discontinuities, and relapses: 1815, 1830, 1848, 1851, 1870. On the other hand, repeated revolutionary episodes had kept the Revolution’s momentum (as well as the fear of that momentum) alive: 1830, which installed the constitutional monarchy; 1848, which soon led to the coup d’état of Louis Bonaparte; the Paris Commune of 1871, which brought about a fierce repression.

It is hardly surprising that literary works, from Balzac to Émile Zola, when not dealing directly with the events of the Revolution, offer repeated allusions and references to them. Old Goriot, the central character of Balzac’s famous novel, is not merely a doting and profaned father, a latter-day degraded Lear or “Christ of paternity” but, as the reader learns, he had been chairman of a revolutionary section, as well as a ruthless profiteer. During the great famine he sold wheat at black market prices to the “coupeurs de tête” (head choppers) of the sanguinary Comité de Salut Public. Danton and Robespierre are repeatedly mentioned with awe, fear, and respect in Stendhal’s The Red and the Black (1831), whose leading epigraph quotes a stark statement about the bitter truth attributed to Danton: “La vérité, l’âpre vérité.” The reader is given to understand that Julien Sorel’s plebeian anger is fraught with a revolutionary potential. As for Germinal (1885), the title of Zola’s novel about a coalminers’ strike published shortly before the year of the Eiffel Tower, it is the name of the month marking the beginning of spring in the French Republican calendar instituted by the Convention in the grim year 1793, the year of the Terror. Yet the word “Germinal” also signals the novel’s hope-filled theme of the moral and political awakening of the working class, implying necessary struggles lying ahead. Zola’s ambivalent title thus points in opposing directions. “Germinal” marks a renewal, the germination of life, a thrust toward the future. It also connotes an anachronistic calendar of the past, associated with violence and destruction.

A bidirectional perspective characterizes the French collective consciousness in the postrevolutionary period. The nineteenth century seemed determined (or condemned) to think forward by looking backward. The future and the past came into ironic tension, not merely because of repeated attempts at “restoration,” at setting the clock back and treating the events ranging from 1789 to the fall of Napoleon in 1815 as a scandalous parenthesis, but because progress-oriented ideologues seemed compelled repeatedly to look back for inspiration to already anachronistic models. French history during the entire century thus appears both linear and repetitive. Commenting on the turbulent events of 1848–51 that led to the imperial regime of Napoleon III, Karl Marx famously observed that historical events and personages tend to repeat themselves, the first time as tragedy, and later as farce. This deflating observation was strikingly illustrated by Gustave Flaubert in the chapter on political clubs in L’Éducation sentimentale—a truly hilarious episode of the novel, describing the orgy of rhetoric and bad faith, the farcical imitations of past public figures, “one copying Saint-Just, another Danton, and yet another Marat,” while Frédéric Moreau, the young antihero, tries to resemble Blanqui, “who in his turn imitated Robespierre.”

Excerpted from The Pensive Citadel by Victor Brombert. Copyright © 2023 University of Chicago Press. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Reviews:

“The Pensive Citadel offers an elegiac account of a life as reader and teacher — and lover of literature who knows how to share that love.” — Peter Brooks, Yale University

“Brombert’s enthusiastic takes on the French classics show what made him a beloved professor, but the reverent accounts of university life and detailed discussions of navigating trends in literary criticism will hold the most appeal for fellow academics. Literature scholars will want to check this out.” — Publishers Weekly