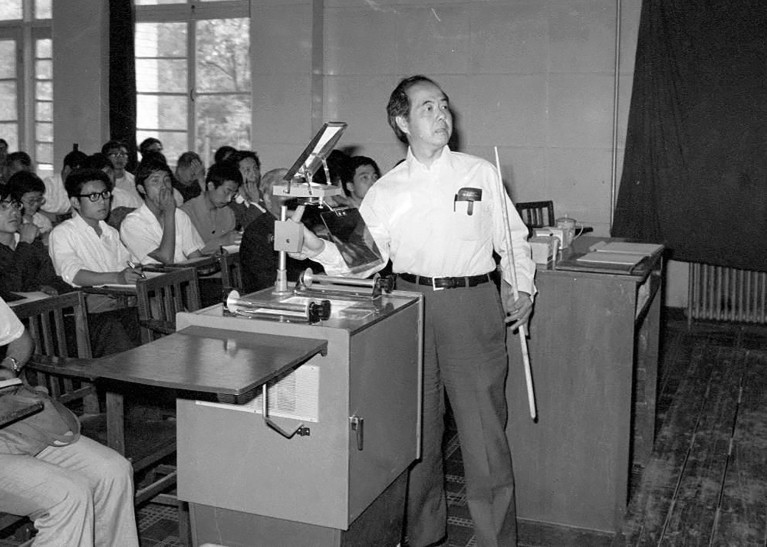

Credit: Xinhua/Shutterstock

Outside the Institute of High Energy Physics in Beijing stands a 5-metre-high metal sculpture. The round, swirling shape of ‘The Tao of All Matter’ invokes the yin and yang of ancient Chinese philosophy — a representation of the inseparable opposites said to form the basis of all things — as well as the ring of the modern particle accelerator a few dozen metres away. The designer was physicist Tsung-Dao (T. D.) Lee. An artistic, inventive and boundary-breaking physicist, in 1957 Lee became one of the youngest winners of a Nobel prize at 30 years old. He shared the award with his compatriot Chen Ning Yang for their work on broken symmetry in particle physics.

Chinese-born but based in the United States for most of his career, Lee, who has died aged 97, promoted engagement between US and Chinese physicists. After China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–76), it was difficult for US universities to evaluate the abilities of Chinese applicants, because they did not know the assessment criteria used in China. Lee set up the China-US Physics Examination and Application system, through which US physicists set exams for Chinese universities to administer, and then went to China to mark them. On the basis of the results, US universities awarded scholarships to nearly 1,000 Chinese students between 1979 and 1989.

Lee’s own education in Shanghai had been interrupted by the 1937 Japanese invasion of China, and by 1945 he was studying physics at the National Southwestern Associated University in Kunming, China. There, at 19 years old, he received a fellowship from the Chinese government to study in the United States, where he completed a PhD at the University of Chicago, Illinois, with the Italian American nuclear physicist and Nobel prizewinner Enrico Fermi as his adviser. He spent the rest of his career at Columbia University in New York City.

How a forgotten physicist’s discovery broke the symmetry of the Universe

Lee earned his own Nobel in one of the most remarkable episodes of twentieth-century science. Physicists were baffled by two particles, known as τ and θ, that were identical except that they decayed in different ways. Treating them as distinct particles created insoluble theoretical problems, whereas treating them as identical defied the fundamental structure of physics known as parity — the idea that objects always behave in the same way as their mirror images.

In 1956, Lee worked on the problem with Yang while the two were spending the summer at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York. Colleagues remember hearing them shouting at each other in their offices in Chinese and English, and drawing equations in the sand on visits to the beach. Did physicists, the two asked, really know that parity structured the ‘weak interaction’ that governed decays of τ and θ? After wading through a 1,000-page book detailing 40 years of work on the subject, they realized that that aspect of parity had not been tested. On 22 June 1956, Lee and Yang sent an article to Physical Review with the title ‘Is parity conserved in weak interactions?’. The journal’s editor insisted that question marks in paper titles were unscientific and changed it to ‘Question of parity conservation in weak interactions’ (T. D. Lee and C. N. Yang Phys. Rev. 104, 254; 1956).

Lee and Yang struggled to interest experimenters in testing a hypothesis widely regarded as preposterous. Only Chien-Shiung Wu at Columbia agreed. She set up an experiment to detect β-decay — the emission of β-particles from nuclei — in ultracold radioactive cobalt. At the tail end of 1956, her team announced that parity was indeed violated in the weak interaction. As another Columbia colleague, Nobel-prizewinning physicist Isidor Rabi, said at a press conference: “A rather complete theoretical structure has been shattered at the base and we are not sure how the pieces will be put together.” By the end of the year, Lee and Yang had been jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery. Lee and others felt that Wu deserved a share of the prize, but she never received it.

China could start building world’s biggest particle collider in 2027

Lee and Yang’s personal relationship did not survive the success of their professional one. To their colleagues’ distress and incomprehension, their clashes became so fierce that universities and laboratories took care to invite only one at a time for visits.

Lee was influential in the evolution of the Brookhaven lab when it faced an uncertain future after a huge high-energy accelerator project was cancelled in 1983. He helped the lab to transform that project into another, the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), which would study the nature of nuclear matter. Lee then established and was first director of the RIKEN BNL Research Center, a pioneering collaboration between Japanese and US scientists at the RHIC.

As an assistant professor at Columbia University in the early 1950s, Lee initiated ‘Chinese lunch’, a tradition in which, at noon on Mondays, physicists would take a visiting seminar speaker to a local Chinese restaurant. Lee insisted on ordering for everyone, and the conversation was usually so lively that participants would have to race back to campus in time for the seminar to begin at 14:10. His research contributed to an astounding variety of fields, including astrophysics, hydrodynamics, particle physics, condensed-matter physics, relativistic physics and statistical mechanics.

Halfway around the world from Beijing, at the Santa Maria degli Angeli basilica in Rome, is another of Lee’s sculptures: ‘Galileo Galilei Divine Man’. In it, the revolutionary seventeenth-century astronomer, philosopher, physicist and artist holds a telescope and robes adorned with heavenly bodies. Both sculpted and sculptor were scientists whose work ventured across boundaries: between scientific fields and between the sciences and the arts.