At the top of Neil Gaiman’s notebook, a doodle of a woman with shaggy hair and huge, black, perfectly round eyes stares out above an early draft of his children’s novel Coraline. In Ursula K Le Guin’s sketchbook, a ring, decoratively pierced and etched with symbols, is drawn cracked in two, just as it appears in the second volume of her Earthsea trilogy. And Susanna Clarke’s notes contain a neatly labelled diagram of the labyrinthine halls featured in her novel, Piranesi.

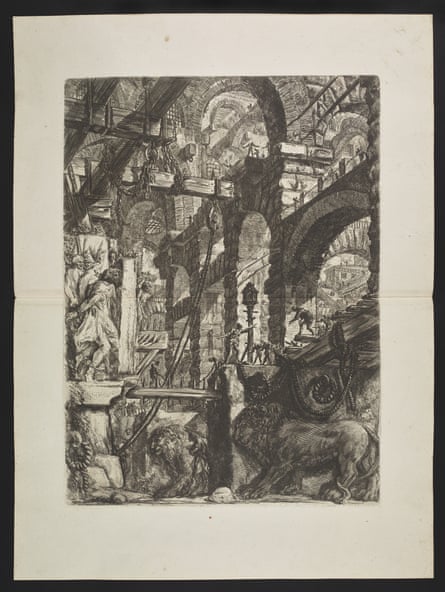

These endearing author sketches of the characters, settings and objects that eventually formed part of bestselling novels are all on display at the British Library’s new exhibition, Fantasy: Realms of Imagination, which runs until 25 February. The show explores the long history of fantasy through manuscripts and early editions of landmark novels, as well as props, costumes and clips from the popular TV shows and films that expanded the genre – from Gandalf’s staff to a snippet of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Maps, posters and adaptation scripts are on display, along with board games and artwork. Visitors are invited to pick up controllers to play a video game based in the Fallen London world, and a room inspired by the American mystery series Twin Peaks – with deep red curtains and a wavy black-and-white floor pattern – features a large screen on which a distorted video of yourself is played back to you. Fandom is also given space, with live-action role play costumes displayed opposite a video of fans being interviewed at London’s Dragonmeet gaming convention.

The exhibition comes at a time when there is a growing commercial appetite for fantasy. On Thursday, London-based publisher Bloomsbury reported record profits in the first half of 2023 thanks in part to a boom in the genre. Sales are being driven by the likes of “romantasy” author Sarah J Maas, whose dazzling popularity on TikTok – the #SarahJMaas hashtag currently has 2.7bn views – led to her dominating this year’s science fiction and fantasy charts. The growth of the genre “is one of the big success stories in publishing in recent years”, says Kathleen Farrar, a managing director at Bloomsbury.

“It’s an incredibly vibrant time for the genre”, says the exhibition’s curator Tanya Kirk, and there is less “patronisation” of it now than there was 20 years ago. Fantasy, like detective fiction or science fiction, was once seen as “too popular”, says Dimitra Fimi, a professor of fantasy at the University of Glasgow who consulted on the exhibit. “It’s that anti-democratic argument, ‘too popular to be serious’, which isn’t true. Sometimes things are popular because they’re brilliant, other times they’re popular for other reasons. But it’s not as straightforward as popular equals not complex enough or not good enough.”

The genre has also often been associated with children’s literature and dismissed for similar reasons. Over the last two decades, however, fantasy has undergone a “reappraisal or re-evaluation” by the academy, says Fimi, and the British Library exhibition, along with recent Tolkien-themed shows at the Bodleian and the Bibliothèque National de France, “stamp” the genre with legitimacy, showing that it is “taken seriously by these institutions.”

Though the books on display are set in imaginary worlds populated by nymphs, trolls and beasts, many are rooted in the real; some are radically political. As visitors pass under the white fairy lights pinned up at the start of the exhibit, one of the first objects they see is Percy Bysshe Shelley’s narrative poem Queen Mab, first printed in 1813. It contains visions of a utopian future in which humans are free. The epic criticises monarchy, religion and industry (“Commerce! beneath whose poison-breathing shade / No solitary virtue dares to spring”). The poem was known as the Chartists’ Bible during the working class movement’s to gain political influence in the 1830s and 40s.

“The usual thing people say is that fantasy is escapist, and it’s nostalgic, and it’s comfort reading. But I would actually push against that, and I would say fantasy very often speaks to its times,” says Fimi. Another book on display, NK Jemisin’s The City We Became, is an urban fantasy that addresses racism and gentrification in New York City. The genre “lets us look at our own world in a new light,” adds Kirk.

after newsletter promotion

The exhibition is accompanied by a festival, Black to the Future, founded by the writer Irenosen Okojie. The programme includes a talk with Bridgerton actor Adjoa Andoh and a premiere of the film Mami Wata with a director Q&A.

“With the stress of the last few years, it’s understandable that people have wanted to distance themselves from the real world and bring a little more magic into their lives,” says Claire Ormsby-Potter, an editor at Gollancz, a sci-fi and fantasy publisher. “I think that level of escapism in stories, which acts as a buffer between reality and our imagination, can really help us to process difficult things in an environment removed from our own lives, and give us an ending to hope for.”