The sprawling California festival “PST Art” promises a dialogue between “two cultures.” But painting and physics may have more in common than their practitioners know.

One spring morning, one wet English morning, John Keats looked up at a rainbow and felt nothing.

The colors that streaked across the sky in Hampstead should have awed him, as they awed people of centuries past — when Noah saw the rainbow as proof of the Lord’s covenant, or when Norsemen believed the rainbow linked this realm to the world of the gods. But by the early 19th century, all Keats could see in the rainbow were optical, verifiable facts. His countryman Isaac Newton had proved that the colors were just sunlight refracted on water droplets, each wavelength bent at a different angle. This was the scientific disenchantment that the young Romantic described in his 1819 poem “Lamia”:

There was an awful rainbow once in heaven:

We know her woof, her texture; she is given

In the dull catalogue of common things.

Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings,

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine —

Unweave a rainbow …

Culture and religion, dreams and angels: for Keats, by 1819, they had all been unwoven. Their poetry had been zeroed out by the cold calculations of physics (or natural “philosophy,” to use his word). And as the modern gospel of progress and rationalization continued to “conquer all mysteries,” artists and scientists began to look at each other with a mutual incomprehension — even disdain — that the British author and chemist C.P. Snow notoriously diagnosed in 1959 as “two cultures.” Art imagines, science answers: and the answer is final.

But go ask Aristotle: Art and science were not always opposites. The Renaissance was an art/science crossover. Without Darwin and Einstein there is no modernism. “PST ART: Art & Science Collide,” the biggest artistic event of the fall season, is all about these two complementary curiosities — and in Los Angeles this September, where Keats would have most likely encountered disappointing rainbows at a West Hollywood happy hour, the denizens of California’s studios and laboratories are going to get to know each other a little better. Nearly 70 exhibitions, of antiquities and contemporary production, in museums and at universities and research centers, will put science in a new frame, and art under the microscope.

Originally called Pacific Standard Time, “PST Art” is an initiative of the Getty — the richest art institution on earth, and among the most intellectually ambitious — to produce a synchronized showcase of Southern Californian cultural clout. This is its third full-scale edition since 2011, and this fall the Getty will be presenting no fewer than nine PST exhibitions, including “Lumen: The Art & Science of Light,” a survey of optics and religion in medieval Jewish, Christian and Islamic art, as well as an overview of Experiments in Art and Technology, a 1960s organization that brought leading American artists to Bell Labs. (Both shows open on Sept. 10.)

But this interdisciplinary festival stretches far beyond the Getty’s Brentwood acropolis. The Getty has committed $20.4 million to institutions large and small in Southern California, and, from the desert to the ocean, PST places a particular emphasis on research-driven exhibitions. There are shows of 1,500-year-old manuscripts and 20th-century aerospace technology, of botanical intricacy and digital minimalism.

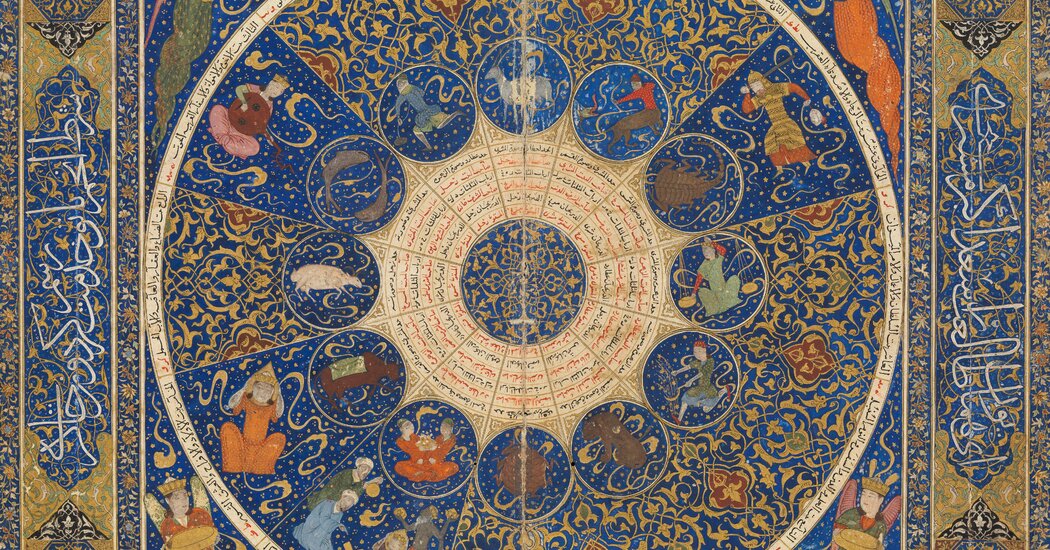

At the Palm Springs Art Museum, “Particles and Waves: Southern California Abstraction and Science, 1945-1990” (from Sept. 14) examines how the astronomers at the Mount Wilson Observatory and the aeronautics engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena inspired painters and sculptors in Cold War L.A. Similar correspondences animate “Crossing Over: Art and Science at Caltech, 1920-2020” (at six locations at the California Institute of Technology, from Sept. 27), which will present rare books of astronomy by Kepler and Copernicus and a new installation by Helen Pashgian, a California sculptor who worked at the science institute in the late 1960s. “Wonders of Creation: Art, Science, and Innovation in the Islamic World,” at the San Diego Museum of Art, assembles miniatures, maps, carvings and navigational instruments to illuminate an intellectual tradition in which art and science were not at odds (from Sept. 7).

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.