Abstract

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), crucial in immune defense mechanisms, are renowned for their propensity to expel decondensed chromatin embedded with inflammatory proteins. Our comprehension of NETs in pathogen clearance, immune regulation and disease pathogenesis, has grown significantly in recent years. NETs are not only pivotal in the context of infections but also exhibit significant involvement in sterile inflammation. Evidence suggests that excessive accumulation of NETs can result in vessel occlusion, tissue damage, and prolonged inflammatory responses, thereby contributing to the progression and exacerbation of various pathological states. Nevertheless, NETs exhibit dual functionalities in certain pathological contexts. While NETs may act as autoantigens, aggregated NET complexes can function as inflammatory mediators by degrading proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The delineation of molecules and signaling pathways governing NET formation aids in refining our appreciation of NETs’ role in immune homeostasis, inflammation, autoimmune diseases, metabolic dysregulation, and cancer. In this comprehensive review, we delve into the multifaceted roles of NETs in both homeostasis and disease, whilst discussing their potential as therapeutic targets. Our aim is to enhance the understanding of the intricate functions of NETs across the spectrum from physiology to pathology.

Introduction

Neutrophils are the first line of defense within the innate immune system, crucial for protecting the host against pathogens. Alongside traditional defense mechanisms, recent attention has focused on unique fibrous web-like chromatin structures, termed neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).1,2 NETs aid neutrophils in immobilizing and trapping pathogens, thereby contributing to host defense.3,4,5 This process relies on associated histones, proteolytic enzymes from granules, and enzymatic myeloperoxidase (MPO).1,2 Accumulating evidence strongly supports the direct and indirect regulatory effects of NETs on both adaptive and innate immunity,6,7,8 playing a crucial role in immune homeostasis. Moreover, NETs contribute specific mechanisms to potentiate immunothrombosis,9,10,11,12 potentially playing a protective role in the context of infection.13

NETs are typically formed and exhibit antibacterial activity in a variety of infectious conditions, including bacterial, parasitic, and fungal infections,14,15 where these pathogens can act as stimuli to induce NET formation. Impaired NET function may facilitate pathogen evasion from the immune system and create a niche for chronic infection.16,17,18 Nevertheless, akin to a double-edged sword, sustained inflammation or persistent stimuli can lead to excessive NET formation, thereby exacerbating tissue damage during inappropriate inflammation. Additionally, NET formation is observed in nonpathogenic conditions, including but not limited to sterile inflammation, autoimmune disorders, metabolic dysregulation, vasculitis, thrombosis, and carcinogenesis when dysregulated.19,20,21 Under sterile conditions, NETs can be induced by interleukin-8 (IL-8),22 immune complexes,23 crystals,24 or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as high mobility group Box 1 (HMGB1).25 Evidence thus far suggests that NETs play dual roles in these nonpathogenic conditions. On one hand, NETs may act as autoantigens in autoimmune conditions, contributing to tissue destruction, amplifying the inflammatory cascade, and promoting thrombosis formation.19,20,21 On the other hand, aggregated NETs formed during sterile inflammation, containing a diverse array of enzymes, have the potential to serve as inflammatory mediators by degrading proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, thereby promoting inflammation resolution and wound healing.10,11 Despite the controversial role of NETs, major studies confirm their more detrimental roles in nonpathogenic inflammation.

Emerging evidence emphasizes the protumorigenic role of NETs in various cancers,26,27,28 primarily due to their contribution to cell damage and regeneration, leading to subsequent excessive inflammation. NETs have been reported to promote tumor cell proliferation,29 metastasis,30,31,32 immunosuppression,33,34 and cancer-associated thrombosis.35 Additionally, NETs can capture circulating tumor cells and facilitate their colonization.36 The antitumor effects of NETs vary depending on tumor type and microenvironment.37 While the debate continues regarding whether NETs inhibit or promote tumor progression, their role in promoting tumor development appears more evident.38 Accumulated NETs provide an immunosuppressive microenvironment favoring the survival of premalignant cells and cancer cells.39 Elevated NET markers correlate with poor clinical outcomes in cancer patients and may serve as prognostic indicators.40,41,42 This review explores the molecular mechanisms underlying NET formation and clearance, along with recent advances in comprehending how NETs contribute to both infection defense and pathologies associated with various diseases, including specific inflammatory, autoimmune, thrombotic, and cancerous conditions. Additionally, we provide an overview of current clinical trials and therapies targeting NETs, offering insights into the development of therapeutic strategies targeting NETs in the clinical practice.

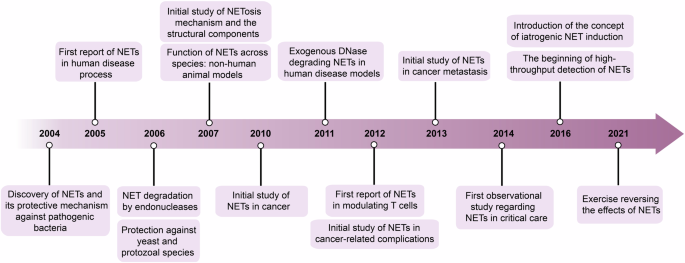

History of research on NETs

NETs have a rich history in research, beginning approximately two decades ago. NETs were first described in the early 2000s as a protective mechanism against pathogenic bacteria,1 which was subsequently expanded to protection against yeast43 and protozoal species. Quickly thereafter, NETs were associated with a variety of human disease processes, first described in the female reproductive tract.44,45,46 As NETs continued to be studied, it was revealed that certain bacteria expressed endonucleases that degraded NETs as a protective mechanism.47,48,49 As these mechanisms for pathogen evasion50,51 became better understood, this led to research developments on harnessing exogenous methods of inhibition or degradation to address human pathology.

In 2007, models of NET activity began to expand into other animal models including fish,52 and zebrafish,53 demonstrating the conserved function of NETs across species. Simultaneously, research shifted toward elucidating the mechanism of NETosis, as well as the structural components that are responsible for their functionality; Pentraxin-3 (PTX3) was identified as a structural protein dotted on NETs54 and the connection with toll-like receptor-mediated activation, which was monumental in the study of NETs in sepsis.

Thus began the era of NETs as prognostic biomarkers in the clinical setting,55,56,57 particularly in the realm of autoimmune disease. Beginning in 2010, the role of NETs in cancer began to emerge,58 first being implicated in non-human animal models. In 2011, exogenous deoxyribonuclease (DNase) came to the forefront as a modality of NET degradation in human disease models59 and has remained a primary agent for NET degradation in current pre-clinical and clinical trials. Causative mechanisms for how their degradation led to these improved outcomes expanded substantially,60,61 leading to studies that focused on inhibiting NET formation62,63 in addition to the degradation that was emphasized previously.

Quickly after the association between human cancers and NETs was made, it became evident that NETs were also responsible for malignancy-related complications such as tumor-associated thrombosis64,65 and metastases.66 Due to the immunogenic environment of cancers, it was natural that at this time the ability of NETs to modulate the innate as well as the adaptive immune microenvironment was also recognized, notably in terms of modulating the T cell compartment.67

The first human observational studies regarding NETs in critical care literature was published in 2014,68 then rapidly expanded to the transplant69 and cardiac70,71 populations. With these observational studies, the in-vivo effects of NETs became better understood72 and the use of NET components in prediction models grew.73,74,75,76 Furthermore, the beginnings of high throughput biomarker detection systems started to be explored.77,78

Beginning in 2016, the concept of iatrogenic NET induction was introduced, with commonly used medical tools such as antibiotics79,80 and ventilators81 implicated in NET formation and subsequent poor outcomes. A key cause of iatrogenic NET induction was found to be chemotherapy, leading to treatment resistance.82 In addition to chemotherapy resistance, significant advances were made in identifying the role of NETs in metastatic disease, with a heavy emphasis in their role in modulating the immune microenvironment,83,84,85 inducing escape mechanisms such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT),33,86,87 and migration.88,89,90,91 This ultimately led to the expansion of research on NET targeting therapies,92,93,94,95,96 and mitigating the adverse effects of NETs. In the 2020s, agents targeting NET degradation or inhibition have been expanded outside of DNase, exploring thrombomodulin97 or necrostatin-198 as promising agents in the preclinical space. Furthermore, more selective targeting of NET components has become more prominent, demonstrating similar outcome efficacy as degradation.99 Interestingly, the role of exercise in reversing the effects of NETs has become a popular topic of research interest100,101 in recent years.

While the connection of NETs and the immune system, particularly in its modulation of other immune players102 has been well researched in the decades of NET-related research, NETs have also been found to connect to a myriad of homeostatic mechanisms, in particular cellular metabolism.103,104 As the knowledge of NETs multi-functionality and its role in disease has expanded in recent years, research has shifted to elucidating its role as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in acute stages of disease,105,106,107 and strides have been taken to elucidate its role in other disease processes through genomics research108 within the past five years. Research thus far has illustrated the wide breadth and comprehensive scope of NET functionality and continues to make rapid advancements (Fig. 1).

History of research on NETs. The major discoveries related to NETs, from their initial identification and role in pathogen eradication to their involvement in diseases such as cancer. It illustrates the progression of research over time and the increasing recognition of their clinical significance. This figure was created by Adobe Illustrator Artwork 16.0 (Adobe Systems, USA)

Structure of NETs

NETs are web-like extracellular filamentous structures released by activated neutrophils. A distinctive feature of NETs is the exposed DNA fibers with diameters of 15-17 nm formed by decondensed neutrophil nuclear chromatin, which are important components of NETs. Although DNA is extruded from NETs for defense purposes, it has both antimicrobial and pro-inflammatory properties throughout the immune responses.109 High concentrations of DNA can chelate divalent metal cations, which can destroy the membranes of bacteria. As a cue for tissue damage locally or programmed cell death, extracellular DNA can be rapidly degraded by circulating nucleases, as well as engulfed by phagocytes.110,111 Impairment of the process might trigger a strong inflammatory response. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is another source of NETs and acts as a DAMP capable of triggering a pro-inflammatory response. The rapid activation of important NETs by mtDNA stimulates other neutrophils, which amplify the inflammatory responses by further releasing NETs through a positive feedback mechanism.112,113

Notably, histones, including H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, are also major components of NETs, accounting for ~70% of the proteins of NETs.114 Although unstimulated neutrophils have the same proportion of all core histones, there are higher amounts of H2A and H2B compared with H3 and H4 in NETing neutrophils.115 Posttranslational modifications of histones also have been found in NETs, even during NET formation. As serine proteases shear the histones of NETs during NET formation, histones of NETs are 2–5 kDa smaller than those unstimulated.116 Acetylation is another modification neutralizing the positive charges in histones, allowing them to detach from DNA and chromatin loss.117 The conversion of arginine into citrulline by peptidyl arginine deiminases (PAD) is named histone citrullination, and it is noteworthy that citrullinated histones have been recognized as one of the major sources of autoantibodies in certain autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA).118,119 In addition, histones also have immunophysiological characteristics, such as antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity, and immunomodulation. Extracellular histones can cause potent pro-inflammatory responses, leading to organ damage and even death.111

Furthermore, cytoplasmic proteins (including S100 calcium-binding proteins A8/A9/A12) and granular proteins (such as MPO), neutrophil elastase (NE), proteinase 3 (PRTN3), cathepsin G, neutrophil defensins) bind in globular patterns to NETs. During the formation and release of NETs, the chromatin swells up, allowing the granule components and cellular components to come into contact.111,120 The toxicity of the various components released by degranulation might cause tissue damage at the site of infection and play an important role in some non-infectious diseases, especially autoimmune diseases and tumors.

Mechanisms of NET formation

Activation of NETs

NETs catch a wide range of bacterial pathogens and prevent their spread. Previous studies have shown that Streptococcus suis (S. suis) can be recognized by toll-like receptors (TLRs), which activate NET formation in an nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX)-dependent manner.121 Although small pathogens exhibit weaker stimulatory effects of NETs, small bacteria have been reported to induce NET formation. This occurs when small microorganisms evade death by phagosomes and tend to aggregate. The size of the external invaders is not a determining factor in activating formation of NETs, but the number of particles in the neutrophil cytoplasm may be a sensitive indicator, as Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) aggregates when exposed to plasma in a murine model of sepsis, which triggers NET formation.122,123 Moreover, NET activation has been perceived in response to virus infection caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).124,125,126,127 In RSV and HIV-induced infections, NETs seem to be beneficial to the immune systems, whereas NET formation in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been shown to be deleterious.

In addition to pathogens, different immunological stimuli (including interleukins, interferons, autoantibodies, and immune complexes), tumor-associated stimuli (including granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), C-X-C motif chemokine ligands (CXCLs)), lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and DAMPs can also promote the formation of NETs. The stimuli may activate the cell surface receptors of neutrophils; for example, immune complexes activate the FcgRIIIb receptor, CXCLs recognize CXC chemokine receptors (CXCRs), C3a recognizes C3a receptor (C3aR), as well as HMGB1 recognizes receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and TLR4.2,128,129 Upon activation of receptors on neutrophils by stimuli, a variety of intracellular signaling mechanisms are further activated, resulting in NET formation. Notably, activated platelets and endothelial cells, the important parts of microenvironment in vivo, have also been reported to exhibit a role in activating NET formation in diseases such as sepsis, stroke and tumors.130,131

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) is a well-known activator of NET formation used for scientific studies. Recent studies have demonstrated that certain metabolites and external environmental factors, and also induce NET activation. Metabolites from gut microbiome dysbiosis and free fatty acids are involved in both infectious and non-infectious diseases by promoting NET formation.132 Cigarette smoke and PM2.5 might contribute to pulmonary diseases through activating NETs as well.133,134 Moreover, bleomycin has been shown to induce NET formation and fibrosis in the lungs of mice.135 Diverse particles also have been shown to induce NET formation, such as hydrophobic nanoparticles, acicular microparticles, and other natural and artificial crystals. Nanoparticles with specific surface properties can be used as adjuvants that stimulate NETs.136 Munoz et al. found that lysosomal destabilization and nuclear disassembly occur simultaneously after exposure of neutrophils to nonpolar nanoparticles, followed by the formation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase-dependent chromatin externalization, suggesting that, in addition to exogenous factors, lysosomal leakage in neutrophils might also trigger NET formation.137 However, to date, the formation of NETs in response to a variety of stimuli is not fully understood.

NET formation pathways

In various diseases, neutrophils are recruited into the microenvironment by diverse mediators to form NETs. Chemokine concentration gradients influence the direction of neutrophil migration. For instance, local tissue injury can lead to increased production of G-CSF, which stimulates neutrophil recruitment.138 Additionally, CXCLs and C-C motif chemokine ligands (CCLs), such as CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL2, play key roles in neutrophil recruitment in diseases.139,140

Although the specific process of NET formation differs depending on the stimuli, it can be categorized as two main pathways (Fig. 2). The first is a cell death pathway termed NETosis, which begins with nuclear delobulation, disassembly of nuclear membranes, a constant loss of cellular polarization, decondensation of chromatin, and eventually rupture of plasma membranes. This process of lytic cell death is that taking 2–4 h usually.20,141 An alternative pathway is non-lytic NETosis that can occur without cell death, whereby chromatin expulsion is accompanied by granular proteins release. These components are formed extracellularly, leaving behind active anucleate phagocytes with microbial phagocytosis and chemotaxis capabilities. This pathway occurs relatively quickly, usually within 5–60 min, but depends on the inducer.20,142

NET formation pathways. NET formation can be categorized into two main pathways. The first type is the classic pathway known as NETosis, which initiates with nuclear lobulation, followed by disassembly of nuclear membranes, loss of cellular polarization, chromatin decondensation, and eventual rupture of plasma membranes. An alternative pathway is termed non-lytic NETosis which can occur without cell death, where chromatin expulsion is accompanied by the release of granular proteins. These components are formed extracellularly, leaving behind active anucleate phagocytes with capabilities for microbial phagocytosis and chemotaxis. This figure was created by Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe Systems, USA)

The lytic NETosis

The lytic NETosis pathway is also known as “suicide NETosis”, as well as NOX-dependent NETosis. Antibodies, microorganisms, cholesterol, and PMA can induce the lytic NETosis.143 These stimuli trigger the activation of signaling pathway proteins, leading to increased cytosolic calcium levels and activation of NOX. Further downstream, oxidase converts molecular oxygen to create reactive oxidative species (ROS). NE is located in the granules of phagocytosis in the resting neutrophils, partly bound to MPO and attached to the granule membranes, with another part in the lumen. ROS induces the activation of NE, as well as its release into the cytoplasm from the MPO-containing azurosome complex. NE binds to F-actin and mediates degradation of actin filaments. NE then translocates to the nucleus and partially cleaves histones to promote chromatin decondensation. Hydrogen peroxide releases NE into the cytoplasm selectively, which depends on MPO. However, inhibition of the enzymatic activity of MPO only delays rather than prevents NETosis, most likely because of the role of MPO in activating the hydrolytic activity of NE on bulky protein substrates.144

The role of the MPO-NE pathway is supported by studies of neutrophils from diabetes patients with hereditary MPO deficiency at high risk of infection.145 Bellaaouaj et al. have reported that mice with NE deficiency are more susceptible to sepsis and death,146 and NE inhibition prevents NET formation and rescues mice from ischemia/reperfusion injury, infection, and tumor.147,148,149,150 Lacking the NADPH oxidase in the respiratory burst pathway can decrease the ability to kill microorganisms, leading to recurrent microbial infections. Similarly, neutrophil elastase gene (ELANE) mutation is one of the most common genetic mutations in neutropenic patients. ELANE-induced neutropenia is associated with dysfunction of the theisprotease enzyme rather than due to NE deficiency. Patients with heterozygous mutations in the ELANE gene might develop severe life-threatening congenital neutropenia, or cyclic neutropenia with mild to moderate clinical characteristics.151

Recent studies have shown another nuclear chromatin-binding protein implicated in NETosis is DEK. Both DEK depletion and treatment with DEK-targeted aptamers attenuate inflammation in vivo and greatly impair NET formation, while NETosis can be reversed by addition of exogenous recombinant DEK protein, suggesting that chromatin decondensation mediated by DEK binding is similar to MPO.152,153

Another factor involved in NETosis is PAD4, which decreases the positive charge of histones, as well as their electrostatic interactions with DNA. The formation of a catalytically active conformation of this enzyme requires five calcium ionophores, which are always employed in studies on exploring the role of PAD4 in NETosis.144 ROS also promotes PAD4 activation.154 Citrullination mediated by PAD4 can be triggered by hydrogen peroxide, which can be reduced by inhibiting NADPH oxidase, indicating an association between PAD4 and production of ROS. The results of experiments with PAD4 inhibitor-treated cell lines or with neutrophils from mice with PAD4 deficiency are difficult to interpret because of low NET yields.135 For example, PAD4 inhibition prevents NET formation activated by nicotine rather than cholesterol crystals.24,155 However, studies with a variety of NET markers have shown that inhibition of PAD4 suppresses NET release in murine models of sepsis and cancer. Moreover, recent studies demonstrate that blockade of citrullination inhibits the pro-inflammatory effects of histones and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques in mice, but not NETosis. In contrast, granule proteases in mouse neutrophils may be indispensable for NETosis in response to calcium ionophores. These findings suggest that citrullination mediated by PAD4 and NE-dependent protein hydrolysis of histones share common features but may play a key role in different situations.144,156

Activation of cell cycle and DNA repair signaling is also important in NETosis. The cell cycle protein-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 is activated during NETosis. CDK6 is required for NETosis, as a previous study has reported mice with CDK6-deficiency are more susceptible to infection. S-phase events (including DNA synthesis and histone gene transcription) are not found during NETosis, while M-phase events (laminin phosphorylation and centrosome segregation) are important the formation of NETs.157 These results suggest that neutrophils utilize the properties of the cell cycle to break down the nuclear membrane. Upon rupture of the nuclear membrane, the dispersed chromatin mixes with granule proteins in the cytoplasm to form NETs.

The non-lytic NETosis

The non-lytic NETosis, occurs through a NOX-independent pathway as known as ‘vital NETosis’, which can be induced by activated platelets, certain microbes, and calcium ionophore carrier A23187. It does not require ROS generation nor result in cell death and is especially critical for acute invasive infection. In contrast to lytic NETosis, neutrophils do not rupture and die, but rather excrete NETs to the outside of the cell by vesicular transport.128 In this pathway, neutrophils can release mtDNA to form NETs when stimulated by LPS or C5a. Furthermore, it has been illustrated that some pathogens can trigger a rapid non-lytic NETosis by activation of TLR2 and C3, such as S. aureus and Candida albicans (C. albicans).109,123 Moreover, platelets stimulated by LPS can also induce non-lytic NETosis by activating TLR4 in platelets. It is important to note that several studies have described a new formation of NETs containing mainly mitochondrial instead of nuclear DNA. Massive and fast release of mtDNA without loss of viability is detected in neutrophils primed with IL-5/IFNγ or LPS. Unlike the non-lytic NETosis containing nuclear DNA, mitochondrial NET formation depends on ROS, since ROS inhibitor treatment or utilization of neutrophils from patients with granulomatous diseases with ROS deficiency, could not release NETs. However, the detailed molecular mechanisms remain unclear.109,156

More importantly, these pathways of NET formation are not completely independent from each other. For example, acetylation modification of histones in NETs upregulates the immunoreactivity of NETs, and the use of low concentrations of deacetylation inhibitors promotes the formation of NETs, but when the dose is increased to a certain level, the NET formation is inhibited.158

Recently studies have shown that NETs formed by neutrophil subpopulations with varying densities play distinct roles in diverse pathologies. High-density neutrophils (HDNs) are typically found in healthy conditions, whereas low-density neutrophils (LDNs) are predominantly associated with pathological settings. LDNs can be co-segregated with the peripheral blood mononuclear cell fraction after centrifugation.159 LDNs often exhibit immunosuppressive effects and are prone to forming NETs. Elevated levels of LDNs have been observed in the blood of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome, and lung infections.160,161,162

Molecular mechanisms regulating NET formation

Kinases in NET formation

Since 2020, increasing evidence has concentrated on the molecules involved in the regulation of NET formation, particularly kinases and receptors.156,163 The kinases implicated in NETosis include kinases activated by calcium influx, or cell cycle regulators, and cytokines involvement in downstream activation (Fig. 3). The protein kinase C (PKC), which is dependent of phospholipid and activated by ester and calcium, in particular PKCα, PKCβ1, and PKCζ, mediates NET formation induced by different stimuli.164 Dowey et al. have demonstrated that PKC inhibitor, ruboxistaurin, reduces pro-inflammatory and tissue-damaging consequences, as well as NET formation. Downey et al. have completed phase III trials for other indications without safety concerns.165 It is also important to clarify that PKCβ/δ/Cζ are all implicated in the oxidative burst, spreading and activation of NET formation by calcium ionophore A23187, whereas in PMA-activated NET formation, only PKCβ is associated with these functions.164 The regulator of cell cycle G1/S transition CDK6, and the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway are also critical for PMA-induced NETosis.157 In addition, receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK), and the mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) are involved in NET formation induced by antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and monosodium urate (MSU) crystals.166,167 Neutrophils from patients with chronic granulomatous diseases are unable to be phosphorylated by PMA-induced MLKL, while RIPK3 genetic depletion in mice blocks NET formation activated by MSU crystals.167

Molecular mechanisms regulating NET formation. The formation of NETs, also known as NETosis, can be initiated by microbial and endogenous stimuli. Various receptors, including those activated by immune complexes, bacteria, fungi, viruses, oxLDL, S100 calcium-binding proteins, and crystals, trigger NETosis via downstream effector proteins. Activated platelets can also induce NETosis through interaction between HMGB1-RAGE and P-electin-PSGL1. Signaling pathways such as MEK/ERK/PKC or JNK induce ROS generation, which is central to triggering NETosis by releasing NE from the azurosome complex. NE degrades the actin cytoskeleton and translocates to the nucleus to drive chromatin decondensation by processing histones. Additionally, chromatin decondensation can be promoted by MPO and DEK binding, as well as the activation of PAD4, which always employs calcium ionophores and mediates histone citrullination. NETosis also relies on CDK4/6 and the segregation of centrosomes. Autophagy and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling are also implicated in NET formation. NOD1/NOD2-linked signaling pathways may promote NET formation through both MPO-NE and PAD4 pathways. EVs can act as endogenous danger signals to induce NET formation by activating multiple receptors, including CLECs. Phagocytic receptors like Dectin-1 inhibit NETosis in response to small microorganisms by sequestering NE to phagosomes, while Siglec-5 and Siglec-9 suppress NETosis by limiting neutrophil activation. This figure was created with the assistance of Figdraw (www.figdraw.com)

Oliveira et al. have identified that in response to different NET stimuli, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) isoforms and related signaling partners can be mobilized, including inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and chemokines. PI3Kα and PI3Kγ isoforms contribute to NET formation across multiple stimuli, whereas the involvement of other isoforms depends on stimuli. Some PI3K isozymes are found to signal through the typical downstream effector of PI3K, AKT, while others cannot. Downstream of PI3K, all stimuli can regulate NET formation with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and phospholipase C γ 2 (PLCγ2). Conversely, the participation of other kinases depends on the different stimuli, both tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and GM-CSF rely on pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) and AKT, and TNFα relies on s6 kinase (S6K).168 In addition, the requirement for PI3K has also suggested the role of autophagy in NET formation, as it also relies on this enzyme. Consistent with this, in a bone marrow-specific murine model of autophagy deficiency, Bhattacharya et al. identified the significance of autophagy in neutrophil degranulation regulation. Neutrophils deficient of autophagy could inhibit degranulation of neutrophils by suppressing ROS production mediated by NADPH oxidase, indicating the correlation of NADPH oxidase with the impacts of autophagy on neutrophil degranulation.169,170,171 Autophagy inhibition (e.g., PI3K inhibitors) can result in a reduction of NET release, while its activation (e.g., rapamycin) enhances the formation of NETs.172 In addition, ROS can rapidly increase the pH value of primary vesicles and then induce autophagy, which is necessary but insufficient to induce NET formation.

Recently, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, and nonreceptor tyrosine kinase janus kinase (JAK), especially JAK2, have been implicated in NET formation.173,174,175 Jak2V617F has been identified as one of the most common driven factors of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Mice carrying Jak2V617F are more prone to NET and thrombus formation, while ruxolitinib, a clinically available JAK2 inhibitor, can eliminate the formation of NETs in a murine model of deep vein stenosis.175

Receptors in NET formation

Neutrophils recognize PAMPs or DAMPs when they are recruited to infectious sites, thereby activating specific surface receptors (Fig. 3). These receptors activate different intracellular signaling mechanisms to regulate a variety of neutrophil functions, including NET formation.

TLRs play a crucial role in recognizing host cells and responding to microbes. Except TLR3, all other TLRs are expressed on the surface of neutrophils in human. TLR2 and TLR4 are necessary in the induction of NOX-dependent NETosis by the fungus Fonsecaea pedrosoi (F. pedrosoi). In bacteria, Wolbachia endobacteria (W. endobacteria) can be recognized and initiate NETosis by TLR2 or TLR6. Furthermore, HIV-1 is captured and killed by NETs through the mediation of TLR7 and TLR8.123,176 In addition to pathogens, substances such as DAMPs, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL), and activated platelets have been reported to promote NET formation via TLRs.131,141,177 Inhibition of TLRs can reduce NET formation, for example, TLR9 antagonist administration significantly abrogates NET formation, as well as cell death mediated by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and induced by NETs.178,179

The cytoplasmic receptors, NOD-like receptors (NLRs), is the second line of defense against pathogens. Alyami et al. found that Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) upregulates the expression of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1) and NOD2 to trig NET formation in a time-dependent manner.180 Another study on diabetic wound healing identified the role of NLRP3/Caspase-1/Gasdermin D (GSDMD) pathway in NET formation and release.181 Uptake or formation of cholesterol crystals in lysosomes can also cause membrane disruption, as well as activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes. Activation of inflammasomes in neutrophils cleaves GSDMD, followed by the formation of membrane pores and release of IL-1β and IL-18, ultimately resulting in pyroptosis or NET formation in hyperlipidemic mouse models.182

Immune cells (including lymphoid and myeloid cells) express a variety of C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) on their surface, for instance, L-selectin, macrophage inducible C type lectin (Mincle), macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 (MIC1), of which Dectin 1 and Dectin 2 are usually expressed on neutrophils. The CLRs are able to recognize polysaccharides of microbial membranes directly and activate the immune responses by promoting the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and the formation of NETs. Numerous studies have reported that viruses may interact with lectins in immune cells via terminal glycan on their surface.183,184 Among members of the human CLRs, dendritic cell/lymphocyte-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC/L-SIGN), LSECtin, as well as spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk)-coupled C-type lectin member 5A (CLEC5A) and CLEC2, have been shown to play roles in virus-associated NET formation and inflammation.185 Stimulation of P-selectin upregulates the expression level of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) and increases the phosphorylation of Syk, thus modulating NET formation in neutrophils.186 Sung et al. have illustrated that extracellular vesicles (EVs) from activated platelets can induce NET formation via activation of CLEC5A/TLR2 heterocomplex, while inhibition of CLEC5A and TLR2 by a bi-specific antibody almost completely abolishes NET formation-induced by EVs.187 Interestingly, besides being involved in NET formation, CLRs can inhibit the release of NETs as well. For example, Dectin-1 acts as a size sensor for microbial phagocytosis by neutrophils to prevent NETosis via blocking NE translocation to the nucleus.122,188

Complement receptors (CRs) are also mainly expressed on lymphoid and myeloid cells, and play an important role in the regulation of innate and acquired immune responses. There are specific interactions between complement factors that eliminate circulating antigens and clear apoptotic cells. One of the first evidence showing the importance of a complement system in NET formation is that neutrophils from mice with C3 deficiency have difficulty in NET formation,189 and those from mice with C3aR deficiency cannot form NETs either.190,191 To date, the most common CRs promoting NET formation are CR1, CR3, CR4 and CR5. In addition to CR1 antagonist, blocking of CR3 can inhibit NET formation in response to certain pathogens.192,193 A recent study has indicated that in neutrophils infected with SARS-CoV-2, the process of NETosis might be amplified by C5a/C5aR1 signaling, while treatment of neutrophils with DF2593A, a selective C5aR1 allosteric antagonist, inhibits NET formation, which provides a promising therapeutic strategy for COVID-19.194

RAGE is a multiligand transmembrane pattern recognition receptor, and its ligands include HMGB1, advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and the S100 family, etc. When activated, RAGE activates multiple intracellular signaling pathways and promotes the production of various inflammatory substances. HMGB1, by binding to RAGE, induces neutrophil activation and promotes the formation of NETs, a process that is dependent on the involvement of NADPH oxidase. The disulfide HMGB1 has also been observed in venous thrombosis to promote pro-thrombotic NET formation mediated by RAGE. More importantly, the employment of HMGB1-neutralizing antibodies eliminates NET formation.195 In the lupus-prone mice, NET formation in the glomerulus is remarkably suppressed in RAGE-deficient mice, along with the improvement of renal pathological scores, suggesting that the blockade of RAGE might be a promising therapeutic target for SLE.196 HBV-induced S100A9 accelerates the formation of NETs mediated by TLR4/RAGE-ROS signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).126 In addition, S100 family calprotectins are also released upon the formation of NETs, shown as the failure of neutrophils from patients deficient in PMA-induced NETosis to release S100A8 or S100A9 in response to PMA stimulation, indicating that these calprotectins might amplify the activation of NET formation.197

Moreover, other receptors have also been shown to mediate NET formation. Multiple immune cells express Fc receptors (FcRs), thus driving humoral and cellular immune responses by facilitating the uptake of immune complexes. In one report, FcγRIIa directly participates in activation of NETosis, while another report demonstrates that FcγRIIa merely promotes phagocytosis and NET formation can be induced by FcγRIIIb through MEK/ERK signaling pathway.198,199 It remains unclear which receptor plays a major role or whether their interactions are critical for the formation of NETs. FcRs also seem to be involved in NET formation during infection of bacteria, as neutrophil exposure to ammoniated S. aureus suggests that activation of FcRs promotes NET release.200 In addition, neutrophil effector functions (e.g., degranulation and NETosis) are also reported to be mediated by chemokine receptors. Only CXCR1/2/4 have been identified to be implicated in NET formation to date.200 For example, CXCR1 and CXCR2 have been confirmed to be involved in mediating chemokines-promoted NETosis in tumors.201 CXCR2 induces NET formation by cooperating with PSGL-1, which signals the recruitment of neutrophils, thereby further promoting deep vein thrombosis.202 Overlapping subsets of immune cells express sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs). Each Siglec binds to specific endogenous glycosylated glycan to initiate signaling programs and participate in cellular responses. Several Siglecs have been reported to play a regulatory role in NET formation, especially Siglec-9. Siglec-9 is considered as a neutrophil checkpoint and can suppress NETosis in inflammation and cancer immune evasion. Delivery of an artificial glycopeptide targeting Siglec-9 to the surface of intact cells could suppress NET formation and induce neutrophil apoptosis. A pair of receptors, Siglec-5 and Siglec-14, are expressed on monocytes and neutrophils, as Siglec-5 promotes bacterial survival through impairing NET formation, while Siglec-14 has opposing effects in the regulation of host immunity.203,204

NETs in health

The bulk of materials associated with NETs are derived from the nucleus, resulting in a significant enrichment of core histones.205 Additionally, these materials contain elevated levels of cytosolic proteins such as S100 proteins, MPO, and granule proteins (NE and proteinase).144 The proteins contained within the reticular structure of NETs serve as the foundation for the physiological functions of NETs.144,206 NETs are integral components in the preservation of homeostasis, as evidenced by their involvement in host defense, immune regulation, immune thrombosis and wound healing, thereby serving beneficial functions to a certain degree (Fig. 4).207,208,209 Comprehending these physiological functions will aid in the formulation of more holistic clinical treatment strategies.210

NETs in health. NETs play a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis. a NET function by capturing and immobilizing pathogens, relying on specific proteins embedded within the NETs to modify the morphological structure of these pathogens, thereby neutralizing and ultimately killing them. b NETs enhance neutrophil defense, promote macrophage polarization, induce pyroptosis, and facilitate pDC differentiation, thereby aiding antiviral functions. They also support CD4+ T cell and B cell activation while potentially impairing NK cell activity. c NETs promote immunothrombosis by activating factor XII, binding VWF, and triggering platelet activation via histones H3 and H4. They also inactivate anticoagulants and facilitate activation of the extrinsic pathway, aiding in pathogen defense. d AggNETs promote inflammation resolution and wound healing by degrading pro-inflammatory cytokines and sequestering NE to protect the extracellular matrix from proteolysis. This figure was created with the assistance of Figdraw (www.figdraw.com)

Host defense

As a foundational element of innate immunity, the primary function of NETs is to defend the host from pathogenic invasion (Fig. 4a).20 NETs effectively combat infections by ensnaring, immobilizing, and neutralizing a diverse array of pathogens, encompassing fungi, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, parasites and viruses.144,211 Neutrophils possess a distinctive microbe-detection mechanism, which enables them to customize their antimicrobial reactions towards pathogens based on microbial size.212,213 The ineffectiveness of phagocytosis in eliminating the large filamentous form of fungi highlights the necessity of NETs in effectively controlling these pathogens, particularly in individuals with MPO deficiency, leading to recurrent fungal infections.214,215,216

Candida albicans, a significant pathogen in invasive candidiasis, has been demonstrated to be effectively eliminated by calprotectin (S100A8/A9) within NETs in vitro and in vivo.217,218 This antimicrobial protein complex functions as a divalent metal ion chelator, exhibiting strong efficacy against a range of fungal pathogens such as Candida albicans, C. neoformans, and Aspergillus spp.219 Upon interaction, calprotectin demonstrates antifungal properties by sequestering Zn2+ and/or Mn2+, crucial elements for the growth of these pathogens.197,220 Moreover, NETs have the capability to alter the cell wall composition of Candida albicans, resulting in the exposure of β-glucan and increased detection by Dectin-1-positive immune cells.221 Aspergillus spp are widely distributed environmental fungi that emit spores, which are consistently inhaled but effectively eliminated by individuals with intact immune systems.222 As previously stated, calprotectin serves as a crucial antifungal agent in combating Aspergillus spp and has the ability to induce irreversible zinc deprivation at elevated concentrations.214,223 In a clinical investigation of chronic granulomatous disease patients undergoing gene therapy, the restored release of calprotectin is essential for protecting against Aspergillus spp and managing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.224 NETs have also been observed to influence host immunity to Aspergillus fumigatus by releasing long PTX3, a pattern recognition receptor that triggers complement activation and aids in pathogen detection.225

The antibacterial properties of NETs continue to be a subject of scholarly discussion, with the potential for NETs to exhibit varying degrees of efficacy in the eradication of diverse bacterial strains.20 The morphological effects of NETs in bacterial infections represent a prominent and direct approach. NETs can alter the morphology of bacteria by ensnaring them with the web-like structure.1,211,226 Imaging techniques utilizing flow chamber systems or intravital microscopy effectively demonstrated the capture of E. coli by accumulated NETs in hepatic sinusoids during sepsis.227 In the absence of bactericidal elements, NETs capture pathogens without completely eliminating them, as they may not disrupt the structural integrity of bacterial cell walls or induce further alterations in bacterial morphology.228,229,230,231 Histones, which are rich in positively charged lysine and arginine residues, have been shown to exhibit bactericidal activity at low concentrations.232,233 Likewise, NE eradicates bacteria through the degradation of proteins located on the outer membrane of bacteria, while also focusing on the virulence factors specific to colonic enterobacteria.234 MPO continues to be active on the extruded NETs, producing ROS-like hypochlorous acid to kill bacteria.211,235 Additionally, NETs play a role in disrupting bacterial biofilms, which can also contribute to alterations in bacterial morphology.236,237 Interestingly, the environment in which NETs are formed affects their ability to kill bacteria. NETs formed under dynamic conditions trap more bacteria but kill them less effectively compared to those formed under static conditions.228

The mechanisms by which NETs defend against viral pathogens exhibit a range of diversity.176,238 First of all, the web-like structure can trap and immobilize viral particles, preventing their spread through electrostatic attraction.239 In addition to mechanically trapping, NETs also possess the ability to attract viral envelopes with negative charges, such as those found in influenza A particles, HIV-1, and norovirus, through the presence of positively charged amino acids. This process leads to the aggregation of these viruses, ultimately aiding in the containment and eradication of the pathogens.239,240 Furthermore, antimicrobial proteins such as MPO, cathelicidins, and α-defensin are attached to the chromatin backbone of NETs.241,242 These proteins have demonstrated antiviral activity against both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses.124,239,243 Additionally, the activity of human respiratory syncytial virus is also impeded by NETs, a phenomenon that may be associated with the presence of serine proteases and bactericidal permeability-increasing protein within NETs.244,245

A series of studies have shown that parasite infections can result in significant neutrophil infiltration and the production of NETs, although most parasites are typically captured but not entirely eradicated.246 In vitro formation of NETs has been documented as a mechanism capable of ensnaring E. histolytica; however, NETs do not impede its proliferation, with additional studies indicating that only a minor fraction of trophozoites are eradicated.247,248 Similarly, Strongyloides stercolaris and Brugia malayi can induce neutrophils to release NETs, which may help trap larvae but does not lead to their death in vitro.249,250 NETs cannot kill Trypanosoma cruzi, the cause of Chagas disease, but they can restrict its invasion and replication.251 Overall, the defensive protective role of NETs in parasitic infections remains poorly understood, potentially due to limited availability of experimental models for investigation.20,246,252

In this chapter, we focus on the reported host defense mechanisms related with NETs. Further research and discussion are needed to understand how NETs eliminate microbes. While NETs play a crucial role in combating infections, their tendency to trigger a systemic inflammatory response, referred to as the “waterfall effect,” can negatively impact host survival, particularly in viral infections.253,254,255 In cases of HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure, elevated NET levels are associated with poor patient outcomes.256 Similarly, excessive NET release in patients with COVID-19 contributes to complications such as coagulopathy and lung damage.127,257,258 These pathological effects are discussed in detail in subsequent sections. Therefore, precise control over the production and breakdown of NETs is imperative in order to mitigate pathogenic inflammation.

Immune regulation

Recent studies suggest that while NETs are part of the innate immune system, they also play a significant role in modulating the functions of various immune cells (Fig. 4b).42,206,259 In light of the crucial role of immune homeostasis, it is essential to comprehensively investigate the interplay between NETs and both adaptive and innate immune responses.260

Neutrophils exposed to isolated NETs activate various neutrophil functions in a concentration-dependent manner, according to several studies.130,261,262 These functions include the induction of granule exocytosis, generation of ROS and the NADPH oxidase NOX2, formation of NOX2-dependent NETs, increased phagocytosis, and eradication of microbial pathogens. Additionally, it has been observed that the activation of neutrophils by NETs involves pathways that entail the phosphorylation of p38 Akt/ERK1/2. Collectively, NETs stimulate neutrophil effector function and bolster antimicrobial defense. Moreover, NETs possess the capacity to connect the adaptive and innate immune responses through the stimulation of B-cell Activating Factor (BAFF) from neutrophils.262,263,264

The plasticity of macrophages renders them essential in the immune response to pathogens, tissue regeneration, and the preservation of homeostasis.265 Studies have demonstrated that the DNA component of NETs contributes to the activation and polarization of pro-inflammatory macrophages via the TLR9/NF-κB signaling pathway.266,267 In a separate study, it was observed that the levels of iNOS, CD80, and CD86, markers associated with M1 macrophages, were markedly elevated following treatment with NETs. Conversely, the expression of CD206, an M2 marker, was significantly reduced.268 Additionally, NETs aid in the transfer of antimicrobial peptides by macrophages, thereby augmenting their antimicrobial capabilities.259 It is important to acknowledge that NETs have the potential to induce caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis in macrophages via HMGB1.269 This interaction additionally aids in combating extracellular pathogens.270 Upon exposure to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, it was observed that NET formation enhances antimicrobial efficacy by promoting macrophage phagocytosis and facilitating the transfer of neutrophil-specific antimicrobial peptides to macrophages.270,271,272 These findings underscore the importance of the crosstalk between NETs and macrophages in achieving optimal bactericidal activity through NET formation.

NETs have a dual impact on the function of dendritic cells (DCs).273 They attract DCs and stimulate them through the IgG Fc fragment via the IIa receptor with low affinity (FCγII), resulting in the generation of interferon-alpha (IFN-α) through TLR9.274 Specific granule proteins found in NETs, such as MPO, HMGB1, and secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor (SLPI), stimulate plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) to produce antiviral factor.275 Furthermore, pDCs have the capacity to induce the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th17 and Th1 cells subsets.133,276 However, it has been observed that NETs have the potential to impede the differentiation and maturation of DCs in response to LPS stimulation.277 Moreover, the treatment of immature DCs with NE resulted in the generation and secretion of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), which in turn facilitates the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs).278

Monocytes possess the capability to undergo differentiation into either DCs (mo-DCs) or macrophages (mo-Macs), with the balance between the mo-DC and mo-Mac fate being subject to adjustable homeostasis.279,280 Furthermore, the incorporation of NETs into monocytes treated with interleukin-4/granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (IL-4/GM-CSF) resulted in the downregulation of IL-4 receptor on monocytes, hindering their full differentiation into DCs while promoting their differentiation into M2 macrophages.281 mo-DCs are a significant contributor to the progression of pathogenic processes in chronic inflammation. Consequently, NETs serve a crucial function in regulating immune homeostasis.282,283,284

Natural killer (NK) cells, a significant subset of innate immune cells, are known to have their function predominantly suppressed by NETs.260 The addition of DNase I to degrade NETs in postoperative immunotherapy for HCC has been shown to enhance the infusion of NK cells and reduce the risk of HCC recurrence, indicating a potential alleviation of the inhibitory effects of NETs on NK cell activity.285 RNA-Seq analysis demonstrated that NETs impede NK cell function via the interaction with carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) during the host’s antiviral immune response.286 Furthermore, in a murine model where NET formation was disrupted, a decrease in dNKs was observed.287

The T cell receptor serves as a crucial mechanism for NETs to engage with T cells, leading to a reduction in T cell activation threshold and enhancement of antigen-specific immune responses.288 Research has shown that Toxoplasma gondii-induced NETs enhance the recruitment of CD4+ T cells and the secretion of TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-6, suggesting that the adaptive immune response is partially enhanced by NETs.289 Notably, CD4+ T cells exposed to NETs demonstrate elevated levels of activation markers, including CD69 and CD25. A comparable pattern of activation marker expression is noted in CD8+ T cells subsequent to exposure to NETs.259,290 Furthermore, NET-associated histones have the capacity to induce the differentiation and cytokine production of Th17 cells through a TLR2/MyD88/STAT3/RORγ-dependent pathway.291 It is imperative for bolstering immunity against fungal and bacterial infections, as well as enhancing anticancer immunity.260 While another study concluded that Tregs are modulated by NETs, which enhance mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and support the differentiation of Tregs from naïve CD4+ T cells through TLR4 signaling.39 NETs may also enhance antiviral adaptive immunity by lowering the activation threshold of T lymphocytes.242 In summary, NETs have been observed to promote T cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation, thereby modulating adaptive immune responses during periods of necessity.

B cells, another important responder to adaptive immunity, have been identified as associated with NETs, in addition to macrophages, DCs, NK cells, and T cells.229,259,260 Upon encountering antigens, B cells undergo rapid proliferation, with the majority of cells differentiating into plasma cells (effector B cells) and generating antibodies. LL37-DNA complexes originating from NETs have been found to possess the distinctive capability of localizing to endosomal compartments within B cells and inducing polyclonal B cell activation through TLR9, as well as selectively amplifying self-reactive memory B cells that generate anti-LL37 antibodies in response to antigens.292,293 In addition, citrullinated histones are recognized as a classic antigen for B cell activation, and the MAPK-p38 pathway represents an additional mechanism through which NETs induce B cell activation.294,295 B cells play a crucial role in mediating humoral immune responses, as their activation is necessary for antigen presentation, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against tumors, as well as antibacterial and antiviral activities.296,297,298,299 Hence, it is possible that the beneficial effects of these functions on health conditions could be further augmented following exposure to NETs.

NETs are essential in maintaining immune homeostasis, but they also activate immune cells such as B cells, antigen-presenting cells, and T cells, contributing to autoimmune diseases including RA, ANCA associated vasculitis (AAV), SLE, and antiphospholipid syndrome.109,300 In tumors, NETs create an immunosuppressive environment that weakens the antitumor immune response of macrophages, CD4+ T, and CD8+ T cells, thereby accelerating cancer progression and metastasis.39,301,302 Notably, the impact of NETs on immune cells varies between tumor and non-tumor settings.260 Additional specific details will be provided in subsequent sections.

Immunothrombosis

Researchers introduced the term immunothrombosis, prompting a shift in contemporary research towards investigating its potential protective role in the context of infection.13 To uphold homeostasis and bolster the host defense against infectious pathogens, the innate immune system initiates local coagulation, leading to microvascular thrombosis, a process that is dependent on neutrophils and NETs (Fig. 4c).9 The development of thrombi is initiated by the interaction of activated neutrophils and monocytes infected with pathogens, as well as activated platelets and coagulation factors. This process serves a protective role by restricting, sequestering, and eliminating pathogens, and can manifest in veins, arteries, and microvessels across various anatomical levels.303,304

NETs contribute a cell specific mechanisms to potentiate immunothrombosis.9,10,11,12 NETs can bind to and activate platelets, forming a platform that boosts neutrophil elastase activity and promotes coagulation.304 NE on NETs degrades and inactivates Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), with help from activated platelets that aid in NET formation. Neutrophil serine proteases facilitate the activation of coagulation by tissue factor, known as the extrinsic pathway. This process allows platelet-neutrophil conjugates to directly stimulate coagulation by increasing intravascular tissue factor activity. Thrombomodulin may undergo degradation via cleavage by NE and inactivation by neutrophil oxidases in NETs. Factor XIIa can be formed during fibrin formation when extracellular nucleosomes within NETs activate the contact pathway of coagulation. Additionally, histone components in NETs can induce thrombosis by activating platelets through TLR2 and TLR4.13 Platelets directly interact with neutrophils in response to bacterial products, inducing the formation of NETs through a process known as NETosis.12 Additionally, the histone components of NETs, specifically histones H3 and H4, have been found to influence platelets by promoting their recruitment and activation.305,306

Immunothrombosis has been proposed to fulfill a minimum of four distinct physiological roles.13,303,306 Firstly, it aids in the capture and entrapment of circulating pathogens, thereby restricting their spread by confining them within the fibrin network. As a second benefit, microthrombi resulting from immunothrombosis in microvessels inhibit tissue invasion by pathogens. Thirdly, the blood clots create a distinct space that enhances the concentration of antimicrobial strategies and their targets, thereby promoting pathogen eradication. Four, microvascular buildup of fibrinogen or fibrin attracts more immune cells to the infected or damaged tissue, enhancing pathogen recognition and immune response coordination.13 In conclusion, immunothrombosis with NETs helps identify, contain, and eliminate pathogens to protect the host without causing harm.303 Therefore, it has been argued that universal use of anticoagulation in these patients cannot be recommended.307

It is imperative to acknowledge that uncontrolled immunothrombosis can lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), especially during sepsis, and increases the risk of thrombosis and cardiovascular issues in individuals with chronic inflammatory or infectious conditions.9,308 The protective phase of immunothrombosis should be rigorously evaluated from a clinical perspective.

Wound healing

Many studies view the role of NETs in wound healing negatively, but there is this is a controversial finding.209 It has been documented that aggregated NETs, which contain a diverse array of enzymes, have the potential to act as inflammatory mediators by degrading pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, thereby promoting inflammation resolution and wound healing.309,310,311 Furthermore, aggregated NETs (aggNETs) have the ability to sequester NE and shield the extracellular matrix (ECM) from NE-mediated proteolysis.309 Bicarbonate-induced aggregated NETs have been observed to encapsulate necrotic regions and wounds. It is evident that aggregated NETs fulfill distinct functions in the context of wound healing compared to other forms of NETs (Fig. 4d).312 Previous research, particularly in diabetic patients, has primarily focused on the association between impaired wound healing and elevated levels of NETs-related proteins. Excessive or persistent NETs have been observed to contribute to delayed healing of diabetic foot ulcers, a topic that will be further detailed subsequently.313,314 In other words, research on the intrinsic mechanisms of different types of NET formation in wound healing is still in its early stage due to the diverse nature of wound formation and healing processes, as well as the various pathways that trigger NET formation.209

In conclusion, NETs are crucial for an antimicrobial defense mechanism within the innate immune system, functioning both as a physical barrier to impede the dissemination of pathogens and inflammatory mediators, and as a means to eliminate microbes through the action of extracellular DNA, citrullinated histones, and enzymes.211,214,226,238 Furthermore, the inflammatory nature of NETs serves to modulate the immune response and activate additional immune cells.205,260,290 NETs exhibit a tendency to aggregate at high neutrophil densities, degrade soluble inflammatory mediators through NET-associated serine proteases, thereby facilitating the resolution of inflammation and tissue regeneration.209,313 It is noteworthy that NETs serve a crucial function in preserving host well-being and physiological equilibrium.

NETs in various diseases

Infectious diseases

As elucidated previously, NETs unequivocally play an essential role in orchestrating the immune response against infectious agents, notably by helping neutrophils immobilize, capture, and kill invading pathogens such as Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria,3,4 virus,126,172,257 fungi,214,217,315 and parasites.316,317 Impaired NET function may promote pathogens’ escape from the immune system and provide a niche for chronic infection.16,17,18 Nevertheless, akin to a double-edged sword, the sustained presence of inflammation or persistent stimuli can precipitate excessive NET formation, thereby exacerbating tissue damage in instance of inappropriate inflammation (Fig. 5).

NETs in diseases. NETs are involved in various human diseases. NETs are central to the immune response against infectious agents, yet their role can be linked to a double-edged sword due to their potential to exacerbate tissue damage under conditions of sustained inflammation or persistent stimuli. NETs are implicated in a spectrum of nonpathogenic diseases, including sterile inflammation, autoimmune disorders, metabolic dysregulation, thrombosis, pregnancy-related diseases, and tumors, when dysregulated. Under sterile conditions, various stimuli, such as IL-8, immune complexes, and crystals, can facilitate the formation of NETs, leading to conditions like gouty arthritis. AggNETs facilitate the resolution of sterile inflammation. NETs are also implicated in pancreatitis and I/R injuries such as brain and liver I/R. In autoimmune disorders, beyond their pro-inflammatory function, NETs have emerged as potential autoantigens, contributing to the production of autoantibodies. NETs contribute to the disease process of T1D, while further investigation is required for their involvement in T2D. Circulating NET markers positively correlate with glycated HbA1c levels and the severity of diabetic complications. Additionally, NETs promote the progression of MASLD, from steatosis to MASH-HCC. NETs are also implicated in both venous (DVT and pulmonary embolism) and arterial thrombotic events (atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, and ischemic stroke). Furthermore, NETs are associated with several pregnancy-related diseases, such as pre-eclampsia, spontaneous abortions, and gestational diabetes, contributing to their pathogenesis. The protumorigenic role of NETs in various cancers has been confirmed, although a bidirectional interplay between cancer cells and NETs is proposed. This figure was created by Adobe Illustrator Artwork 16.0 (Adobe Systems, USA)

While NETs effectively ensnare pathogens, certain pathogens have developed mechanisms to evade this process. Various pathogens, encompassing a spectrum including V. cholerae, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus genera, P. aeruginosa, N. gonorrhoeae, M. tuberculosis, N. brasiliensis, Plasmodium, Mycoplasma, Leishmania, and Leptospira, produce both endogenous and secreted endonucleases. These enzymes degrade the extracellular DNA scaffold of NETs, thereby dismantling and circumventing the entrapment.207,318,319,320 This evasion facilitated by endonuclease promotes subsequent invasion and dissemination from primary sites to distant organs and the circulation,319 which contributes to the exacerbation of inflammatory pathological conditions, including sepsis.

Sepsis represents a condition characterized by lethal dysfunction of multiple organs and is associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality.130,321 During the early stages of sepsis, neutrophils are recruited from the blood to the infection site and release NETs.208,322 Studies have elucidated that dysregulated NET function during the early stages of infection contributes to the persistent systemic inflammation that initiates the development of sepsis.16,130 In contrast, as sepsis progresses, excess NETs damage tissue, increase vascular permeability and promote organ failure.16,93,322,323 Circulatory NETs in the bloodstream were significantly elevated and NET markers were also increased in patients with sepsis.324,325,326,327 A growing body of evidence reveals that in sepsis and acute injury, NET-bound histones are cytotoxic because of their ability to compromise cell membrane integrity.328,329 Meanwhile, other NET proteins, such as defensins and NE can disrupt cell junctions.20,317 In murine models of sepsis, a study observed marked platelet aggregation, thrombin activation, and fibrin clot formation within NETs in vivo.330 Aggumated accumulated NETs contribute to the sustained hyper-immunothrombosis in sepsis, which leads to lethal DIC complications in patients.131,303,331

NETs are regarded as the main players in antiviral immunity.15 Neutrophils and NETs have been reported to have protective effects in the early stage of viral hepatitis.332,333 A study indicated that NET release was decreased in patients with chronic HBV infection, and correlated negatively with hepatitis B surface Ag, hepatitis B E Ag, and hepatitis B core Ab levels.333 Nevertheless, HBV C protein and HBV E protein might inhibit the release of NETs by decreasing ROS production and autophagy.333 This suggests that impaired NET function may promote viral escape from the immune system and provide a niche for chronic hepatic virus infection. However, in HBV-related acute chronic liver failure (ALF), circulating neutrophils display a significantly heightened propensity to form NETs, which is closely associated with adverse patient outcomes.256,334 Excessive generation of NETs is widely acknowledged as a mediator of further pathophysiological abnormalities following SARS-CoV-2 infection.335,336,337 Elevated NET release has been documented in numerous patients with COVID-19, contributing to detrimental coagulopathy, immunothrombosis, and pulmonary endothelium damage within the alveoli.257,335,338 Inhibition of NETs in patients with COVID-19 has been shown to mitigate thrombotic tissue damage associated with COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and mortality.338,339,340 Moreover, NET-derived histones have been identified in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with ARDS,340 underscoring the pivotal pathogenical role of NETs in lung injury.

In the context of infectious diseases, NETs exhibit dual roles. During the initial phases of infection, their normal function aids in pathogen clearance and prevents the transition of inflammation into a chronic state. However, in conditions such as sepsis and acute injury, NETs assume a detrimental role, compromising cell membrane integrity, exerting cytotoxic effects on epithelial and endothelial cells, and contributing to immunothrombosis formation.303,329,341 NET-mediated damage may exacerbate rather than constrain certain infections during chronic inflammation. Consequently, strategies aimed at optimal NET inhibition at pertinent disease stage represent potential strategies for infection management.

Sterile inflammation

In contrast to pathogen-targeted mechanisms, sterile-associated NETs may entail heightened deleterious effects.20,128 Under sterile conditions, NET formation can be facilitated by various stimuli including but not limited to IL-8,22 immune complexes,23 crystals,24 or DAMPs, such as HMGB1.25 The deleterious impact of NETs on tissues manifests through direct cytotoxicity towards epithelial and endothelial cells, thereby potentiating tissue inflammatory cascades.342,343 Additionally, the influence of NETs extends to the modulation of inflammatory cytokines either through direct or indirect impact on diverse immune cell populations.

In sterile crystal-mediated inflammation, microcrystals including monosodium urate (MSU), calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate, calcium carbonate, calcium phosphate, calcium oxalate, and cholesterol can stimulate neutrophils to release NETs.310,344 Crystals of MSU monihydrate in joints and soft tissues elicit an acute inflammatory condition commonly known as gouty arthritis.345 Within the joint, MSU crystals instigate the release of inflammatory mediators, orchestrating the recruitment of neutrophils and subsequent NET formation.167,346,347 Infiltrated NETs contribute to the acute, profoundly painful, and tissue-damaging inflammation observed within the joints.344 NET formation in MSU crystal-induced arthritis is influenced by diverse factors, including the presence of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β.348 Neutrophils demonstrate increased release of NETs in response to synovial fluid from patients with gout, albeit partially abrogated by the IL-1β antagonist.349 Conversely, studies have unveiled that the excessive accumulation of aggNETs facilitates the resolution of gouty inflammation by encapsulating MSU crystals, degrading cytokines and chemokines, and inhibiting neutrophil recruitment and activation.310,350,351 These findings highlight the potential role of aggNETs as a mechanism promoting the spontaneous resolution of gout, thereby presenting novel therapeutic avenues. However, the precise underlying mechanisms are not fully understood.

Within the milieu of atherosclerosis (AS), circulating cholesterol form monohydrate cholesterol crystals, thereby fostering the formation of atherosclerotic lesions.352,353 These cholesterol crystals serve as potent inducers of NET formation, and in concert with cholesterol crystals, NET augment the release of cytokines released from macrophages via the IL-1/IL-17 and NF-κB signaling pathways.24 NETs have been discerned within the luminal regions of murine and human atherosclerotic lesions, as well as arterial thrombi, implying the potential NET formation across all stages of AS progression.354,355,356,357,358 Notably, within an atherosclerosis mouse model deficient in NE and proteinase 3 (PR3), NETs fail to generate, consequently exhibiting diminished plaque size.24,359 Collectively, NETs-derived extracellular components exhibit cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory attributes, culminating in cellular malfunction and tissue injury, thereby suggesting a nexus between lipid metabolism, inflammatory immunity, and atherosclerosis.360 In patients with suspected or established coronary artery disease, heightened levels of dsDNA and MPO-DNA complexes in plasma demonstrate a positive correlation with both the severity and quantity of atherosclerotic vessels.361,362 Consequently, strategies aimed at inhibiting NET release or the dissolution of NETs may present a promising therapeutic avenue in the context of NET-mediated AS and thrombosis.

In pancreatitis, studies substantiated that bicarbonate ions alongside calcium carbonate crystals can elicit the formation of aggNETs within the ductal tree via a PAD4-dependent signaling pathway.344,363 Besides their implication in the inflammatory insult to the pancreas, the presence of aggNETs within pancreatic ducts can precipitate catheter obstruction and foster the onset and progression of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP).363 Histological analyses of tissue specimens and pancreatic juice samples obtained from patients with pancreatitis have revealed the presence of aggNETs.363 A study suggests a fundamental role of NETs in gallstone formation, with inhibition of NET formation demonstrating efficacy in inhibiting gallstone development in vivo.364 Administration of DNase I to mouse models resulted in a marked reduction in neutrophil infiltration and tissue damage within the pancreas.365 Cumulatively, NETs exacerbate biliopancreatic duct obstruction and exacerbate inflammation, culminating in the manifestation of SAP. Furthermore, NETs contribute to multi-organ injury, infected pancreatic necrosis, sepsis, and thrombotic events associated with SAP.365,366

The involvement of NETs in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury has generated recent attention. The reperfusion subsequent to abrupt blood flow restoration frequently triggers cerebral IR injury following an episode of cerebral ischemia.367 Neutrophils are prompted to release NETs in response to various stimuli, including platelet activation and the presence of IL-8, DAMPs, and TNF-α subsequent to ischemic stroke.368 The accumulation of NETs exacerbates inflammatory processes, thrombus formation, and neuron apoptosis.369,370 Constituents of NETs, such as MPO, histones, and other enzymes contribute to the leakage of blood-brain barrier. Furthermore, in individuals afflicted with ischemia-induced Alzheimer’s disease, heightened levels of amyloid-β (Aβ) precipitate platelet activation, leading to release of HMGB1 and subsequent NET formation, exacerbating disease progression.371,372 Notably, inhibition of NETs has been confirmed to facilitate neovascularization,373,374 indicating a potential therapeutic avenue in mitigating ischemic injury. The pro-inflammatory function of NETs has also been substantiated in liver I/R injury, exacerbating the inflammatory response and liver injury subsequent to I/R.100,375,376 DAMPs emanating from stressed hepatocytes, such as HMGB1 and IL-33 released from liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, serve as pivotal instigators for neutrophil infiltration and subsequent NET formation.375,377,378 Moreover, membrane-nonpermeable superoxide generated during I/R implicated TLR-4 signaling pathway activation, which subsequently instigated NOX and subsequent NET formation.379 Remarkably, interventions such as DNase treatment or inhibition of PAD4 have demonstrated considerable efficacy in mitigating liver inflammation in liver I/R.377

The similarity of NETs in infectious diseases and sterile inflammation lies in their dual role of both protecting and causing harm. In infectious diseases, NETs help clear pathogens and prevent chronic inflammation but can also cause cytotoxicity and contribute to immunothrombosis in conditions like sepsis. Similarly, in sterile inflammation, NETs, triggered by stimuli such as IL-8 and DAMPs, can cause direct cytotoxic effects on epithelial and endothelial cells, exacerbating tissue inflammation. In both scenarios, NETs can have beneficial and harmful effects on tissues and overall health.

Autoimmune disorders

Accumulating evidence from in vitro, in vivo and clinical diagnostics suggests significant involvement of NETs in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune disorders, including but not limited to RA, AAV, SLE, and antiphospholipid syndrome (Fig. 5). NETs have emerged as potential disruptors of self-tolerance, serving as reservoirs of autoantigens that contribute to the production of autoantibodies characteristic of autoimmune disorders.380,381 Additionally, components of NETs are implicated in exacerbating the inflammatory milieu by facilitating complement activation and activaion of other specific immune cells, such as B cells and antigen-presenting cells, thus perpetuating the autoimmune responses.292,382,383,384,385

RA represents as a chronic systemic disease characterized by progressive joint inflammation and variable extra-articular manifestations.386 Central to its pathology are the anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs), which exhibit high specificity for RA and can instigate the formation of pathogenic immune complexes within the affected joints.387,388 Neutrophils are abundant in the inflamed joints of patients with RA, displaying an augmented propensity for spontaneous NET formation.389,390,391,392 Moreover, this propensity for NET generation escalates upon stimulation with RA synovial fluid and ACPA-positive RA serum.389,392 Elevated levels of MPO-DNA complexes and cell-free nucleosome are observed in the serum of patients with RA,393,394 with their concentrations correlating with clinical parameters and ACPA titers in patient sera.389,393,395,396 Accumulated NETs release novel autoantigens, including citrullinated histones, which may further fuel the autoimmune response in RA.389,397 ACPAs have been reported to recognize autoantigens presented on NETs, especially the citrullinated histones.398,399,400 Additionally, NETs have been implicated in disrupting the cartilage structure and facilitating its citrullination, thereby exacerbating synovial inflammation.401 Overall, NETs play a central inflammatory role in RA and represent a significant source of autoantigens capable of eliciting pro-inflammatory responses within various organs, including the lungs and synovium, in patients with RA.129,402,403 Furthermore, NETs and NET-derived products hold promise as biomarkers for RA disease activity.