Droughts in the coming decades could be longer than projected by current climate models, a new study published Wednesday in Nature warns.

The international team of scientists examined potential biases that could skew climate models used to make drought projections under Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change midrange and high emissions scenarios. The researchers corrected for the bias by calibrating those models with observations of the longest annual dry spells between 1998 and 2018.

By the end of this century, they found that the average longest periods of drought could be 10 days longer than previously projected. Trouble spots included North America, Southern Africa, and Madagascar, where the newly calibrated models showed that the increase in the longest annual dry spell could be about twice what the older models predicted.

“Our study pinpoints global regions where current climate model projections of drought increases may be underestimated,” said lead author Irina Petrova, a hydrological extremes researcher at Ghent University in Belgium. The new information can help raise awareness of growing drought risks for populations in the affected areas, “but also should call for the attention of policymakers and governing organizations, prompting them to reassess future drought hazards in these regions and take adequate actions.”

The study identified a drought hotspot in southwest North America, including the southern states of the US and northern parts of Mexico, she said. The findings suggest that droughts in some parts of the region could be five days longer than projected “as early as 2040, nearly 60 years sooner than previously anticipated,” she said.

In contrast to most of the planet, the new study suggests that, in central East Asia, dry intervals between rain storms are decreasing at a rate four times greater than suggested by non-calibrated models under both IPCC emissions scenarios.

“Our finding of a significant underestimation of future decrease in dry period length in central East Asia is notable in itself, suggesting potential for increased future flood risks in the region,” Petrova said. But she cautioned that the region’s climate is complex and that the uncertainties associated with observations in that region made it hard to calibrate the models.

In any case, she said, “It is no longer in doubt for us that most of the global land will experience an increase in dry extremes in the future. A significant portion of the global population is already living under water stress… creating an urgent situation that demands immediate attention.”

Worse than expected

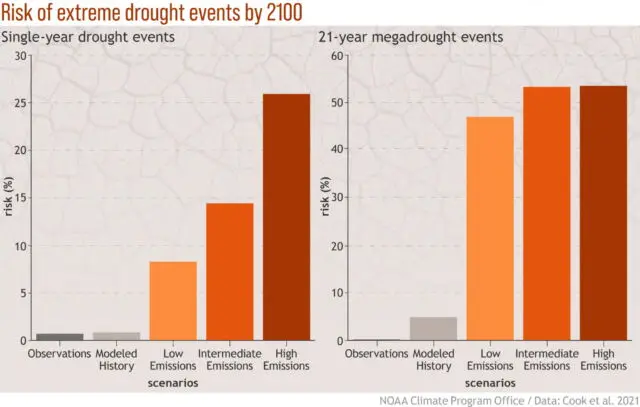

The finding that droughts could be longer than projected by the IPCC fits a pattern of recent research showing that various climate impacts are accelerating and could be worse than expected and arrive sooner than projected by the panel. Its reports are only issued every five to seven years and represent a scientific consensus that can be diluted by politics.

Notable in the recent research are signs of a slowdown of the key heat-transporting current in the Atlantic Ocean, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current, which sustains a temperate climate in much of northwestern and western Europe. Several recent studies provide evidence that the current could weaken enough by 2100 to cause an extreme climate shift with global ripples.

The surge in the average global temperature during the last 18 months has also taken some climate scientists by surprise, raising the question of whether the rate of warming is faster than projected by the IPCC, and whether that will push parts of the climate system past dangerous tipping points in the near future.

The answer varies depending on exactly which segments of time are compared. But some researchers, like former NASA scientist James Hansen, have said that accelerated warming will push the planet’s average temperature past the target of the Paris Agreement of limiting human-caused warming to well below 2° Celsius above the pre-industrial baseline by 2050.

With many signs pointing out danger ahead, the findings of the new study emphasize the need for a reassessment of drought risks around the world and highlight the importance of correcting existing biases in climate models to increase confidence in their projections, Petrova said.

Those “systematic biases are known to contribute to divergence in model projections of dry extremes,” the scientists wrote. The new study, integrating detailed observations of dry spells from 1998 to 2018, aims to narrow those gaps to make more accurate drought projections.

Simultaneous wet and dry extremes

Michael Mann, director of the Center for Science, Sustainability & the Media at the University of Pennsylvania, said there is plenty of research showing that climate models fail to resolve some of the processes that are involved in summer season extremes, including floods, heat waves and droughts.

One of the big challenges is that models can’t fully recreate some of the physical processes that cause rainfall deficits, and they show big differences in the strength of relevant climate feedbacks, like soil moisture and clouds.

“We argue that the models are underestimating the impact that climate change is already having on these extreme events,” said Mann, who was not involved in the new research. “So it isn’t surprising that an approach that weights models by their ability to match real-world patterns projects greater extremes.”

The World Meteorological Organization warned in 2019 about simultaneous wet and dry extremes. Mann said it’s not a contradiction to see both more extreme rainfall and worse drought.

“When it does rain, there’s more rainfall in any given event, in part because a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, moisture that can be converted into rainfall,” he said. “But rainfall events are fewer and far between, and warmer soils lose more moisture through evaporation,” which leads to longer spells of drought between rainfall.

In recent years, simultaneous extremes have been evident at global and regional scales during every season, over land and across the oceans. During the last few days in Europe, multiple forest fires erupted in Portugal after summer heatwaves and drought, while at the same time, parts of Poland, Czechia, Romania, and Austria went from the hottest summer ever measured to an extreme extended rainstorm with deadly flooding in a matter of days.

“The catastrophic rainfall that hit Central Europe is exactly what scientists expect with climate change,” said Joyce Kimutai, a researcher at the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London who is part of a World Weather Attribution team assessing the role of global warming in the floods.

“A warmer atmosphere heated by fossil fuel emissions can hold more moisture, leading to heavier downpours,” she said. “Weather station data also indicates that bursts of September rainfall have become heavier in Germany, Poland, Austria, and Czechia.”

She added: “We are on track to experience more than 2.5° Celsius of warming before 2100, so we need to adapt to the impacts of extreme weather that is occurring more and more frequently. We need to stop burning fossil fuels, but we cannot forget about adaptation.”

It’s clear that even highly developed countries are not safe from climate change, added Friederike Otto, also a climate researcher at Imperial College London and a leader of the World Weather Attribution team.

“As long as the world burns oil, gas, and coal,” she said, “heavy rainfall and other weather extremes will intensify, making our planet a more dangerous and expensive place to live.”

This story originally appeared on Inside Climate News.