Credit: Rohini Godbole

Rohini Godbole, Indian particle physicist and ardent advocate of women in science, passed away today at age 71. She was an honorary professor at the centre for High Energy Physics at Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru.

Godbole was born in Pune and studied physics at the local Sir Parshurambhau College and then at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. She specialised in field theory and phenomenology during and after her doctorate at Stony Brooks University in USA in the late seventies. She received India’s civilian honour Padma Shri and the French Ordre National du Mérite.

I first knew Rohini as the short-statured dynamite of the Department of Physics at University of Mumbai. Before it became fashionable, she wore canvas shoes with a saree to the Kalina Campus in Santacruz, Mumbai. She would walk into the green shed of the canteen and speak in nice and loud tones, enjoying all the attention she attracted.

‘Higgs search will direct future of particle physics’

I remember feeling both awe and amusement for Rohini. For a social science student like me, she was the first flesh and blood ‘ woman in science’ I got to know. The fact that she did theoretical physics and not experimental physics, which is what women in science generally did, was another point I noted in the mid 80s. A more personal relationship with Rohini began when my partner, K. Sridhar, registered for his doctoral thesis with her at the University. After Sridhar and I were married, she would refer to herself as my ‘mother-in-law in physics’. The jest made me warm up to her.

She and I would often exchange exasperated notes on our respective roles. It reflected to me what was wrong with scientific cultures and institutions and how individuals, across genders, found it difficult to survive with dignity. What I will always remember though is the delectable pao bhaji we ate on the streets of Mumbai, outside the campus, after Sridhar, her first doctoral student, got his PhD.

It was quite common to hear, in whispers and openly, of how women were undeserving to make it to the institutes of fundamental research, participatory to the departments of theoretical physics. Women were often seen worthy of teaching in ‘ local colleges’ and not enough to occupy positions in the ivory towers of research institutions. Rohini often spoke about how hard it was for her to not only survive but to ‘make it’ in the world of science, particularly theoretical high energy physics. I doff my hat to her for pushing through it. She had to play the masculinist game hard, harder than the men.

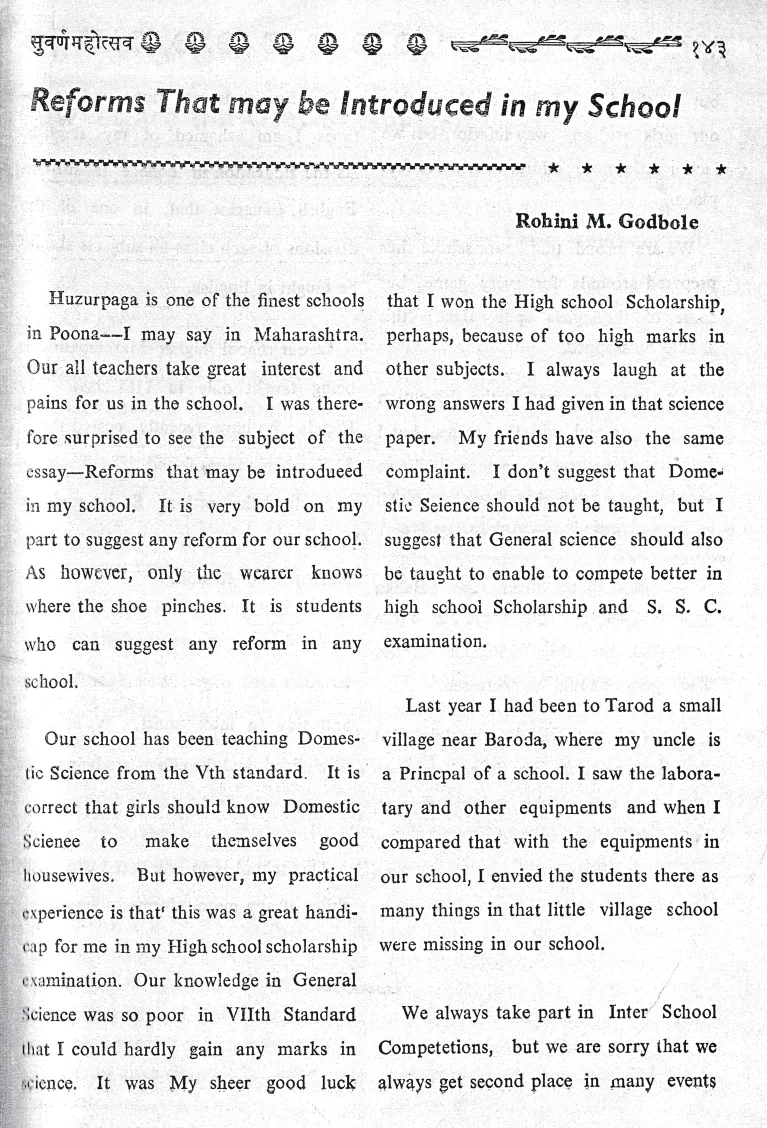

Scan of an article Rohini Godbole wrote while still in high school calling for a reform of the school curriculum to include general science and not just ‘domestic science’ for girls. Credit: Archives at NCBS.

Did she have to pay a price? Probably, yes. As she writes in The Girls Guide to Life in Science: “My journey has been a wonderful one, but I must say that I was quite unsuccessful in resolving the conflict between my personal and professional lives. Not having children is perhaps my one regret. I know, though, that it requires a big helping of luck for a woman to combine a successful career in science with a happy family, given the lack of institutional and social support structures. In my generation, it was falsely assumed that we could be superwomen, managing both career and life perfectly!”

My last intimate conversation with Rohini was somewhere in 2011, when I was already involved in building the field of feminist science studies in India and she got deeply committed to the cause of building gender inclusivity in science. I remember she said to a room full of people,” You and I shall never agree, we have a fundamental difference on the question of gender and science.”

The fundamental difference she referred to was that while she agreed with me that the cultures of science were gendered, patriarchal and discriminatory to women due to no fault of women, she drew her boundary. She didn’t think there was a need to push the question of gender and science any further — into critically examining the nature of scientific method and scientific theories. I learnt to respect our difference and commit myself to understanding the complex relationship between women practitioners of science, like herself, and feminist critics of science, like me. Her voice of determined caution always echoed in my mind.

Her commitment to science was something she held on to with great tenacity. In many ways, she defined the generation of women in science in India that began taking cognisance of the challenges of women in science, a generation that began seeking accountability from within.

As we bid adieu to this little giant of a woman, I would like to appeal to the world she leaves behind — let’s make it easy, let’s make it kind, let’s make it compassionate for women to enter science, and stay there.