Jamillah James/Photo courtesy Jamillah James

“Curator time operates on a very different timescale than everyone else’s,” Jamillah James jokes as she reflects on the inevitable last-minute decisions and minor crises leading up to the opening of “The Living End: Painting and Other Technologies, 1970-2020” at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA). Bringing together decades of work, the exhibition pushes against the old idea that painting is dead and highlights how the medium has continually evolved.

In our conversation, James shares her curatorial journey, reflecting on the shifts in painting over the past fifty years—from traditional techniques to the integration of technology—and how digital and social media are redefining its boundaries. Her goal? To rethink painting’s place in contemporary art and reconsider its legacy.

Tell me about the exhibition—it’s been quite the journey to get here, hasn’t it?

It’s definitely gone through a few different lives. This exhibition was originally planned for my former institution, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, but when I joined the MCA, I brought this show with me. Over the years, the exhibition has evolved, seen different forms, and ultimately arrived at what it is now after years of research. I think now it’s a critical moment for this show to come together because these conversations about painting’s place in contemporary art are still so relevant, especially in the way some artists are rethinking painting as a practice.

So, painting isn’t dead, then!

No, not at all! It never really went anywhere. Painting is fundamental—one of the rudimentary things any art student starts with before they branch out into other media. There have been moments when people worried it might become obsolete—like when photography or digital art entered the conversation. But painting is still here and has simply evolved over time. As critics and historians observe trends in the arts, sure, certain things come in and out, but painting never died. It’s just taken on different forms over the past several decades.

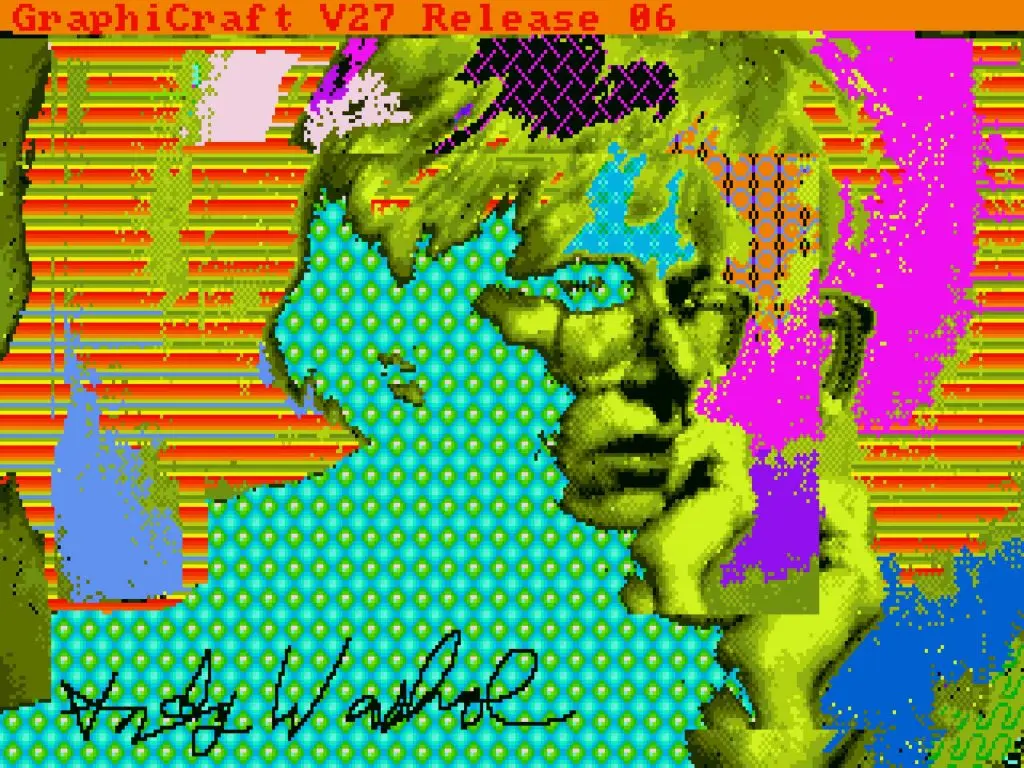

Andy Warhol, “Untitled,” 1985, digital image. The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc/Photo: The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

I completely agree. Technology has really opened up new avenues for artists—whether through video, computers, or automation. And with the rise of AI and other digital tools, it feels like it’s reshaping our understanding of what a painting can be. Do you think these technologies will become a central part of the conversation?

Absolutely. That conversation is inevitable. My strategy with this exhibition was to encapsulate fifty years of thinking and production, cutting off at the point where NFTs become a more dominant part of the conversation. The way this show operates—and how art history operates—is as a progression over time, with precursors to what follows. There are a couple of works in the exhibition that explore ideas like mass production, as seen with NFTs, and the use of digital capabilities to create worlds or images. Many works in the exhibition, even those from earlier periods, share some of these ideas and move toward what is ultimately the state of visual culture right now.

Are there any specific works in the exhibition that speak to this?

One work that comes to mind is by New York-based artist Siebren Versteeg, who will present a legacy version of his 2017 piece “A Rose.” In this work, Versteeg wrote an algorithm that generates endless iterations of Jay DeFeo’s iconic painting “The Rose” [1958-1966]. DeFeo spent eight years layering the surface to the point where the painting reached two tons in weight, and it’s pretty much a permanent installation at the Whitney Museum, where it remains indefinitely.

What Siebren Versteeg’s work does is make it possible to see different versions of “The Rose” as the program runs, essentially rethinking the central image over and over again. The earlier 2017 version allowed people to take home a copy of one of the iterations. So, there’s this “projection,” if you will, of technology, giving people ready access to an artwork they can hold onto digitally—or physically, if they prefer.

Cheryl Donegan, “Whoa Whoa Studio (for Courbet),” 2000, video (color, sound), 3 minutes, 21 seconds/Photo: Electronic Arts Intermix, New York.

That’s incredible! Technology has definitely redefined the boundaries of painting. It’s such an exciting time to witness the fusion of traditional art forms with technology. How do you see this synergy reflected across all the works in the exhibition?

Part of my work, as a curator, is establishing connections across time, and it’s hard to encapsulate the vast history of painting—or even a single tendency—within one exhibition. I know this won’t be the definitive word on the subject; many have explored it before, and many will continue to do so. The artists in this exhibition, whose practices span different eras, reflect a shared lineage of thought. Though the title might suggest otherwise, the show includes work from the mid to late sixties influenced by computers, drawing and painting, connecting to later artists who engage with computers in new ways. This thinking establishes context across times and geographies, which is key to my work as a curator and central to how I made certain choices in the exhibition.

I love the title “The Living End.” It feels like there’s an irony to it, suggesting an ending that never really happens.

Right! Another part of the title that’s really a play on words is the idea of technology. If you think about the etymology of the word, it’s not talking about computers or cameras—it’s about technique. It’s about making things with your hands, having expertise in a particular field or subject. So, painting itself can be seen as a form of technology, which is one of the contentions of the exhibition because it’s a way of making something.

And what I love about the show is how it also critiques traditional notions of painting, especially its place in the Western canon. It feels like a lot of the works push back against the old idea that painting is this elite, privileged medium. How did you navigate those difficult conversations?

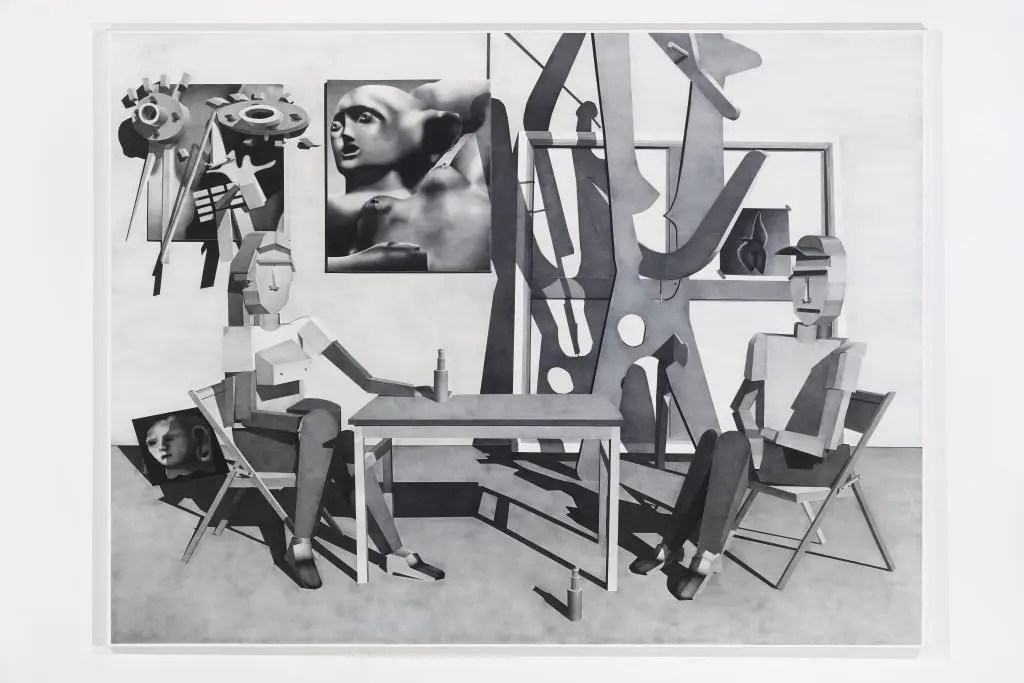

Avery Singer, “The Studio Visit,” 2012, acrylic on canvas, 72″ × 96″ × 1 3/4.” Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth/Photo: Roman März

[laughs] Let’s pretend they won’t be difficult! But seriously, part of my job as a curator is to always represent, as best I can within a particular show, the viewpoints outside the dominant narrative. It’s well understood at this point that the Western canon is subject to revision because it has not been inclusive in its breadth and reach.

You see many institutions around the world doing these very thoughtful re-installations of their collections—adding new artists, adding new works. This exhibition is focused on including artists who represent subjectivities and concerns that challenge the usual progression of art history. The show makes a point to highlight contributions from artists of color, women artists and queer artists.

More than half the checklist consists of these voices. Still, at the center of this exhibition is painting—that’s what the title suggests. It sets up a dialectic of sorts, where painting is the core, and all other technologies are almost secondary. Painting is the focus.

This exhibition critiques painting as a practice, a methodology, a history and as a commodity or object. I know I’ll be asked, “Where’s the technology?” and I’ll have to keep repeating that the show is fundamentally about painting. That’s the heart of this exhibition. And everything kind of floats around that nucleus, but also encroaches on the nucleus by painting.

That ties into the critique of the “singular genius,” right? The image of the lone male painter.

Exactly. I mean, the exhibition works to re-center certain images in the public imagination. When people think of a painter, they often think of figures like Jackson Pollock, Leonardo da Vinci, or Claude Monet. It’s much rarer to hear them mention Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, or a whole range of other women artists who have made significant contributions to the field of painting.

I want to show that there are multiple histories within this trajectory. For example, an artist like Sturtevant created what she called a repetition of Frank Stella’s “Bethlehem’s Hospital”—her version of it. By appropriating the work of her male contemporaries, she sparks a conversation, a back-and-forth, about how to center women’s contributions to painting while still being in direct dialogue with these historical figures. It raises important questions about whose work is prioritized in our understanding of art history, particularly the history of painting, and who we consider a “painter.”

Sayre Gomez, “Behind Door #8,” 2018, acrylic and urethane-based paints on canvas, 84″ × 120″. Collection of Rebekah and Ilan Shalit. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler/Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

That’s so important. What are you hoping people take away from this exhibition? There’s so much to unpack here.

I hope viewers come away understanding that there’s no single way to make a painting—and no singular history for an artist to engage with and critique. I think one of the more surprising elements in the exhibition will be the place of video and performance in the show—it’s one of the subversions that are key to the thesis of this show.

The relationship between video and painting is shaped by hierarchy, economics and institutional exposure. If you were to audit a museum’s collection or a gallery’s roster—unless it’s focused specifically on new media—you’d find that video and performance artists are often underrepresented. One of my goals with this exhibition is to explore what happens when you place video, performance and painting together in the same room.

By doing that, you invite a different kind of conversation for the viewer. Moments like this appear throughout the show—whether it’s a younger artist’s take on landscape painting or artists like Ken Knowlton and Leon Harmon tackling the nude, but through the lens of computer-assisted drawing and early computer graphics. It’s about expanding how a viewer encounters painting, moving beyond a narrow, myopic view of what painting can be, especially with the influence of technology. The video camera, the internet—these tools have deeply impacted painting, and that’s part of the conversation here.

I look forward to seeing how this plays out in the exhibition.

For example, there’s also an early Warhol in the show from 1965, part of our collection. Warhol consistently thought about how to mass-produce images and explored various ways to do that. Screen printing was central to his practice as an artist, and when he began using computers in the 1980s, it extended those same ideas. It connects Warhol’s 1960s work—like his silk screens—to contemporary artists like Wade Guyton, who uses printers to make his paintings, or Petra Cortright, who uses digital programs to produce works that are later printed. There’s a clear continuum, and I want people to engage with that, to understand that things don’t happen in a vacuum—least of all in the arts.

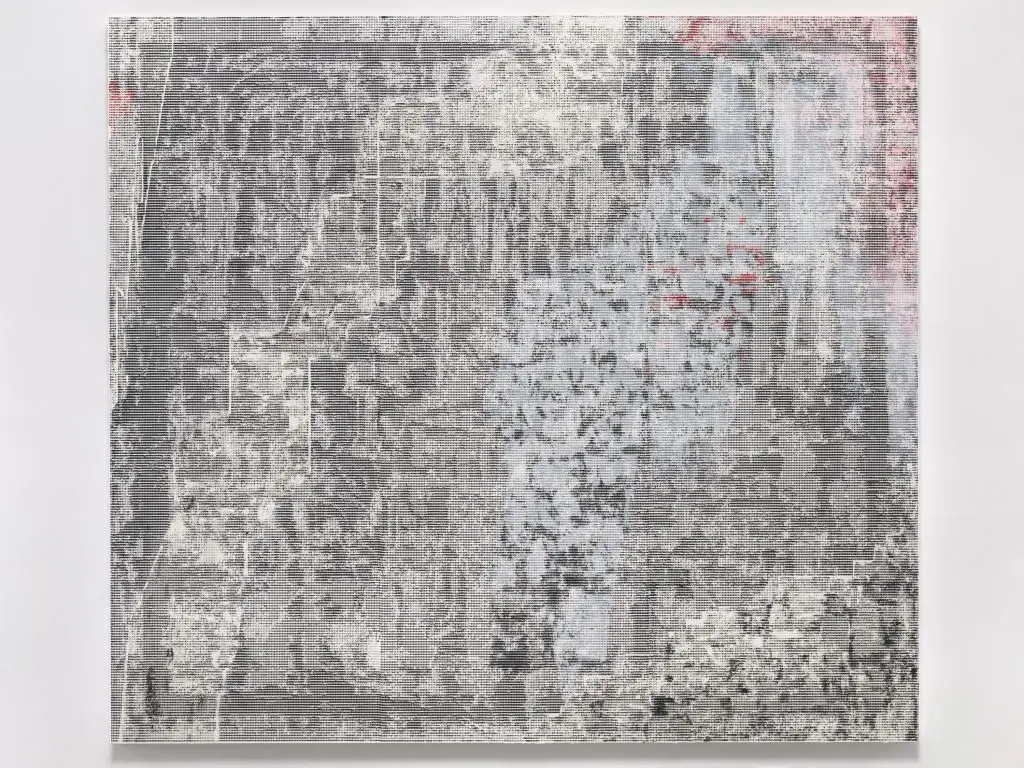

Jacqueline Humphries, “MN+//ssss,” 2023, oil on linen, 114″ × 127″. Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York/Photo: MCA

Any interactive pieces we should look forward to?

Actually, there are a couple of interactive works in the show. One of them is by Andy Warhol, from his foray into using computers in the early eighties. He was invited to do a project on the Amiga computer, and you can find footage of the event where he showcased the technology and created several images, some based on his earlier works, using this computer. For the exhibition, in collaboration with the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, we’ve organized to bring the Amiga emulator so that visitors can interact with the same setup Warhol used to produce those images.

That’s very cool. Warhol is always such a great thread to follow through time, especially as a link between the past and present, the physical and the digital. Speaking of which, I’m curious—how do you see social media playing into this evolution? It feels like the role of the artist has shifted significantly on many levels.

That’s a good question. It’s been a huge shift. Digital and social media have completely reconfigured the relational landscape. We all know how they’ve changed the way we relate to each other, but also how we relate to the world and the things in it, including art. Video cameras, for example, have expanded the ways artists can work, and this is also true for social and digital media. These platforms have increased interaction between artists and the public, which has been a critical development over the last twenty years.

They’ve also changed the way the public interacts with institutions, as we’ve seen time and time again, with the public speaking back to institutions and speaking back to artists by proxy. This shift moves artists away from the insularity of the studio or institution and into direct engagement with the public. Social and digital media have enabled artists to work in new ways, allowing them to discover, consume and appropriate different source materials.

From my perspective, artists now have a unique responsibility as ambassadors to the world of images. Social media has made expressing those ideas more efficient and has also made their work more visible and accessible outside of traditional institutions. And accessibility is a key focus of this exhibition—how artists have made art historical ideas more accessible and how painting, as both objects and concepts, has become more available to the public.

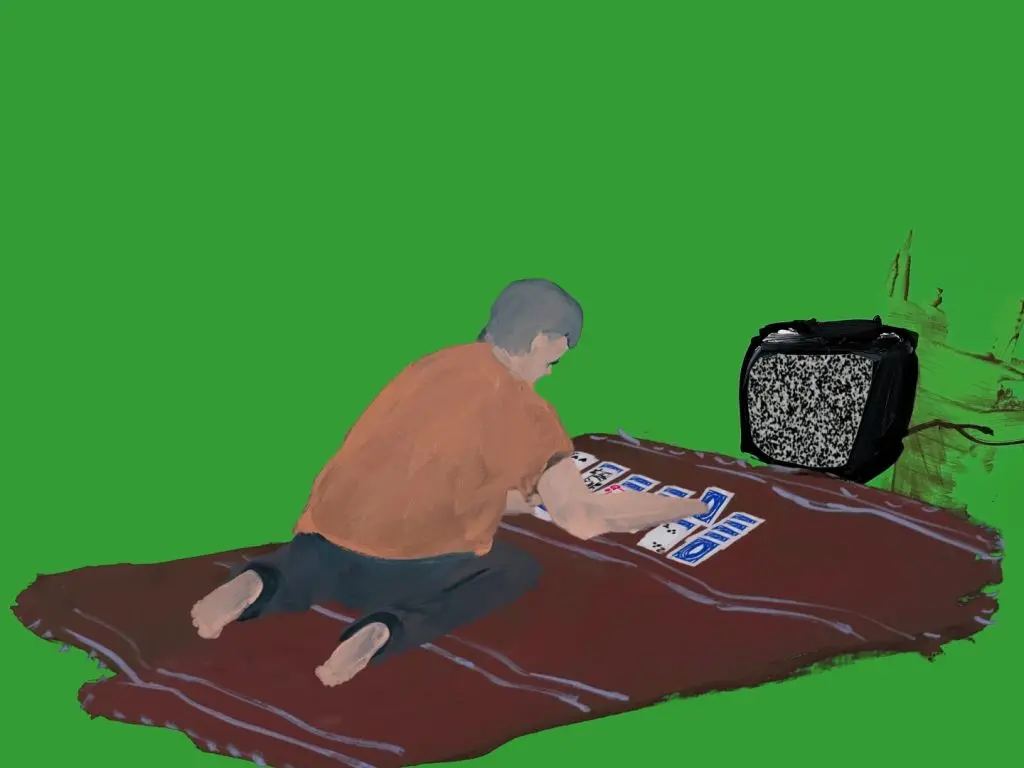

Tala Madani, still of “Solitaire,” 2023, single-channel color animation, 5 minutes, 58 seconds. Courtesy the artist; 303 Gallery, New York; and Pilar Corrias, London/Photo: Tala Madani

Definitely. With the exhibition now just around the corner, looking back, how was the process for you—beyond the endless research?

It’s been a long time coming. The idea for this show started casually about ten years ago. It’s been interesting to rethink things from the vantage point of 2020 and to see how much has progressed since then. I was living in New York in the early 2010s and mid-2000s, and a lot of the inspiration for this show came from artists I knew who were working within a post-internet framework. Many of them were exploring painting as a site for critique, given its long history.

That’s where painting sits—within the field relative to itself. And this has been an ongoing concern for artists. Several artists in the exhibition take up the history of action painting or explore issues related to figures like Yves Klein, who instrumentalized women’s bodies in his work. Feminist critique runs throughout the exhibition, and it’s what connects artists working in the 1970s to those working today who are still grappling with these ideas.

Looking ahead, how do you see the future of painting evolving?

You know, it’s hard to predict the future. But I think the future of painting will look very much like its past—paint on canvas, or some other substrate, hung on a wall. That won’t change. What will evolve are the methods and contexts in which painting happens. The artists in this exhibition show that progression and offer possibilities for what’s next.

I’m really excited to see how it all comes together. Do you have a favorite piece you’re particularly excited about?

What I always say is, I love my children all the same.

“The Living End: Painting and Other Technologies, 1970-2020” runs from November 9 through March 23, 2025, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 220 East Chicago.