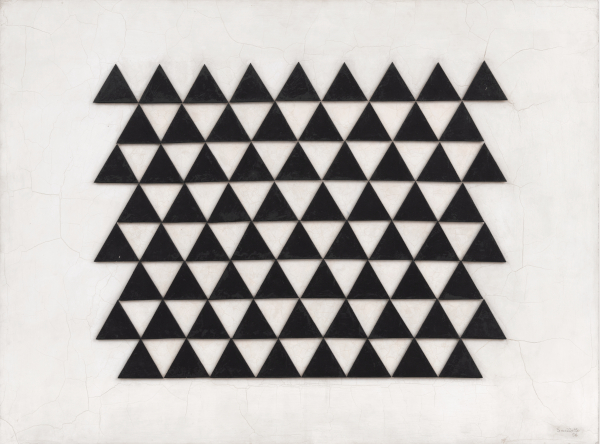

Luiz Sacilotto “Concreção 5629,” 1956, synthetic enamel on aluminum, 26.8″ x 31.5″ x 0.2″/Photo: MAC USP

On December 9, 1952, a group of seven artists (five of foreign origin and two Brazilians) opened an exhibition of abstract “concrete” art, that is, a strand of abstract geometric art based on European constructivism, at the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art. The group called themselves Grupo Ruptura and, much like the avant-garde movements of the early twentieth century, launched a manifesto with short, imperative phrases declaring their intentions: “The aim is to break with the ‘old,’ namely: all varieties and hybrids of naturalism; the mere negation of naturalism, that is, the ‘wrong’ naturalism of children, the insane, the ‘primitives,’ the expressionists, the surrealists, etc.; the hedonistic non-figurative art, a product of gratuitous taste that seeks only to excite pleasure or displeasure.”

The group’s leader (and main writer of this manifesto), Waldemar Cordeiro (1925-1973), had returned from Europe four years earlier, bringing with him ideas and references on geometric abstract art, from Mondrian to Malevich’s suprematism, but mainly about the theoretical apparatus of the Bauhaus and the Ulm School of Max Bill (1908-1994). The “Rupturists” were also influenced by the theory of “pure visibility,” by German philosopher Konrad Fiedler (1841-1895), although it remains unclear to this day how much they absorbed or truly understood it.

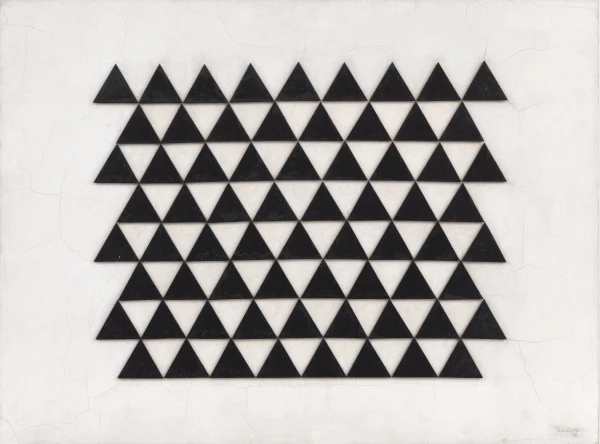

Luiz Sacilotto “Vibrações verticais,” 1952, enamel on wood, 15.6″ x 21.1″ x 1.7″, Banco Itaú Collection/Photo: MAC USP

The thesis they defended, however, was the construction of art as a project of total transformation, capable of permeating people’s daily lives, influencing industry, and organizing life on various scales: from the fine arts to design, from architecture to the city. They understood that a visual language built with simple elements—lines, colors and planes—had the power to transcend geographic, social and cultural boundaries (hence Fiedler’s influence), capable of touching people from different contexts and backgrounds. In support of a project to renew art with broad social impact and aligned with the premises of life in an industrial society, antithetical to the manufacture of things associated with the countryside and rural life, they proposed a rupture (hence the group’s name) with figuration in art and with types of abstraction centered on the individuality of artists, which they considered unsuitable for the times they lived in.

Fiedler (whom they revered) also asserted the necessary mediation of language for the understanding of everything around us. Since it cannot completely coincide with “the expression of being,” it can be seen as a possible alternative to help contribute to “the form of being.” Once valued, language should be subordinate to the sense of pure vision, because it is the source of all immediate apprehension of the world, fulfilling our urgent need to understand the surrounding reality. He states: “We are accustomed to reducing to other spheres of our spiritual and intellectual life all the material of reality that vision provides us, instead of striving to understand it as such.”

In a world that was definitively opening up to mass consumption, vision (the gaze) became the main tool for accessing, communicating and seducing individuals—the consumers—in a capitalist and industrial society. Hence, the correspondence between visuality and industry in the early 1950s, and, in the arts, a utopian attempt to subvert capitalism using this same correspondence.

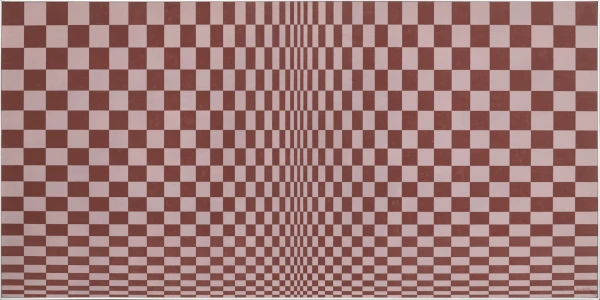

Luiz Sacilotto “C 8101,” 1981, tempera on canvas, 23.8″ x 47.3″, Private Collection/Photo: MAC USP

It is worth noting that a year before the founding of Grupo Ruptura, in 1951, the first São Paulo International Art Biennial took place, and the subsequent editions definitively paved the way for the production and reception of abstract art in Brazil (geometric and non-geometric strands), as well as the formation of a significant collection of modernist art at the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo (MAM SP), which was later donated in full (by the patron Ciccillo Matarazzo) to the Museum of Contemporary Art, University of São Paulo (MAC USP). Now, MAC USP is hosting a major retrospective of one of the most important members of Grupo Ruptura, the painter and sculptor Luiz Sacilotto (1924-2003). The newly opened exhibition, titled “Sacilotto Contemporâneo: Cor, Movimento, Partilha” (Contemporary Sacilotto: Color, Movement, and Sharing) curated by Ana Avelar and Renata Rocco, brings together 113 works by the artist, with a special focus on his production from 1970 to 2003, the year of his death, “when he delved into optical-kinetic experimentation combined with color exploration.”

Broadly speaking, Sacilotto’s artistic trajectory can be divided into three phases. The first, before his involvement with Grupo Ruptura and his adherence to São Paulo concretism, began between 1938 and 1947, when he attended the Escola Profissional Masculina do Brás (alongside figures like Marcelo Grassmann (1925-2013) and Octávio Araújo (1926-2015)) and took classes at the Associação Brasileira de Belas Artes in São Paulo. During this period, the artist developed a figurative painting style, of modernist extraction, with great similarities in style, choice of themes, and treatment of pictorial matter to the production of the proletarian painters of the Grupo Santa Helena. Art critics generally refer to Sacilotto’s production during this period as “expressionist art,” which it was not, in fact. The second phase is concretist art, where referents disappear, and the material facture itself becomes simpler with the assimilation of industrial materials and techniques.

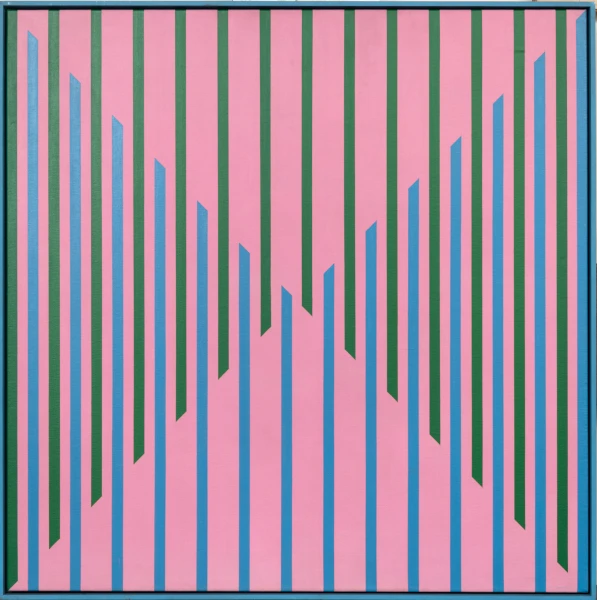

Luiz Sacilotto “C 8860,” 1988, vinyl tempera on canvas, 42.5″ x 42.5″, Private Collection/Photo: MAC USP

In this second phase, Sacilotto transitioned to abstraction, strictly adhering to the principles and directions endorsed by Grupo Ruptura. For example, the work “Concreção 5629” (1956, MAC USP Collection), made with synthetic enamel on an aluminum plate, consists solely of a series of black triangles lined up and stacked on a white background. Seen from a certain angle, the painting produces the image of larger triangles that sometimes advance toward the eye and at other times recede into the frame. This effect is also pursued in the aluminum cut and folded sculptures, with minimal interventions suggesting the artist’s “hand.” In the sculpture “Concreção 5730” (1957), for instance, he works on an aluminum square: through symmetrical cuts and folds, he creates a support that allows the piece to be self-supporting, without the need for a base.

Waldemar Cordeiro defined him, due to his adherence to concretist principles, as the “mainstay of concrete art.” It is a rudimentary art in terms of the choice of planes and colors, and it is precisely in this simplicity that its elegance resides. In “Concreção 6048” (1960), an oil painting on canvas, the artist again uses a triangle scheme, now combined in black and white to form rectangles tilted to the right and left, with the composition repeated at the bottom of the canvas. The background, painted violet, shows how Sacilotto gradually moved toward a more sensual, or at least less rigid, effect in relation to color. The artist then began collecting and cataloging a wide range of pigments, classifying more than 300 shades, which were used to create his paints.

The third phase of his artistic career began after an almost ten-year hiatus (between 1965 and 1974, he dedicated himself almost entirely to the craft of locksmithing), with the production of works that delve into references from kinetic art and op art. From 1975 onwards, the influence of the work of Julio Le Parc and the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV), active between 1960 and 1968 and including artists such as François Morellet, Francisco Sobrino, Yvaral, Vera Molnár and Victor Vasarely, becomes visible. For Sacilotto, this meant creating a painting that plays with our perceptual apparatus, causing the eye to perceive movements in the geometric patterns, which degrade in size, colors, or both. In a canvas like “Concreção 7959” (1979), for example, we feel the inner space of the painting swell at the center as if something is about to explode, with a clear reference to Vasarely’s patterns.

Luiz Sacilotto “C 9993,” 1999, acrylic on canvas, 23.6″ x 23.6″, Private Collection/Photo: MAC USP

In this phase, it is as if the rigor of the concretist phase is replaced by the pleasure of inventing situations that challenge our ordinary perception, making us question what we are actually looking at, similar to the hall of mirrors in amusement parks or circuses.

The exhibition “Sacilotto Contemporâneo: Cor, Movimento, Partilha” is extensive, well-organized and documented, with works on loan from important national and international institutions, such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, among others. However, as in other instances, even in past exhibitions at MAC USP, the curatorship missed the opportunity to use the museum’s rich collection, which includes, for example, Vasarely’s “Chillan” (1951) and Lygia Clark’s “Plano em superfícies moduladas n.2” (1956), among other pieces that could have interacted with Sacilotto’s work over the decades covered.

The challenge of holding large monographic retrospectives of modern artists often lies in treating them in the eighteenth-century manner of the genius (according to Kant), that is, viewing them as solitary creators of an insular work that, in the end, should be understood by the public only through their idiosyncrasies and lived experiences.

Alternatively, it is assumed that the reality of the work itself, the plastic fact per se, is enough for its meaning to be structurally accessed. However, it is important to remember that the theory of “pure visibility” has always been, and remains, just a theory.

“Sacilotto Contemporâneo: Cor, Movimento, Partilha” (Contemporary Sacilotto: Color, Movement, and Sharing) is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, University of São Paulo (MAC USP), Avenida Pedro Álvares Cabral, 1301, Ibirapura, São Paulo, through January 26, 2025.