By David D’Arcy

In this illuminating show you’ll recognize the state that (for now) is home to Donald Trump and was the habitat for Jeffrey Epstein and a wide range of other dangerous creatures.

Floridas: Anastasia Samoylova and Walker Evans at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, through May 11

Anastasia Samoylova, Gatorama, 2020. Photo: MET

Anastasia Samoylova captures Florida’s charm (or the state’s decline) in Gatorama (2020), a picture of a baby alligator against the background of scuffed bathroom tiles and a dripping pipe. This is nature made manageable. It’s the kind of Floridiana that Carl Hiaasen would love.

Yet Florida is anything but manageable. Hurricanes regularly level the built environment and carnivorous alligators deprived of their shrinking natural habitat stalk small dogs and grandmothers on golf courses.

In another picture, Beachgoer, Naples, (2021), the Russian-born Samoylova, who moved to Florida in 2016, offers a tactile torso-level look at the tattoo of a pistol on a man who also has a real knife strapped to his waist.

Don’t look to the Tourism Bureau or to glowing real estate ads for images like Samoylova’s of the Gunshine State, which was home to “Monster” mankiller Aileen Wuornos and remains a busy zone of operation for drug cartels. In this show you’ll recognize the state that (for now) is home to Donald Trump and was the habitat for Jeffrey Epstein and a wide range of other dangerous creatures.

Anastasia Samoylova, Beachgoer, Naples, 2021. Photo: MET

Walker Evans traveled to Sarasota in 1941 to photograph what was then an emerging travel destination, a small city sitting amid the orange groves on the Gulf Coast south of Tampa. He had been there once before. This invitation came from Karl Bickel, a retired newspaperman and a transplant, as almost everyone in Florida was in those days. Bickel was preparing a book about the region that he called The Mangrove Coast: The Story of the West Coast of Florida.

Sarasota was the winter home of the Ringling Brothers Circus, so elephants, baboons, and all sorts of acrobats were there. So were pelicans, odd creatures to the eyes of those who never saw them in the flesh.

As usual, Evans was less interested in places than in the people who were in those places — old “winter resorters” in thick wool coats, service employees for the tourists, African Americans in a then-segregated state. As happens with Evans, each wave of humans earns its own layer of images.

Evans’s trip to Florida is one point of departure for the current Met exhibition. Besides showing rarely seen pictures by the 20th-century master, the show introduces the Russian-born Samoylova (b. 1984), whose eye takes you to the many Floridas that Evans did not see.

A classic Evans scene is Florida Roadside, in black-and-white, like all of his 1941 Florida pictures. It is an agglomeration of signs, mostly advertising cola. The uneven surfaces of the ads are multilayered — past and present, commercial and homemade — and the juxtapositions make you think of him as an American surrealist. The signage intimates a cutting cultural critique that Evans applied in Florida and elsewhere: by selling the new, we paste over the past, often after smothering it, or hollowing it out, as in the empty Spongediver’s Suit, Florida (1941), the title garb positioned to sit in a chair as if it were a movie monster resting between shots. Postcards that Evans collected in Florida and sometimes arranged in groups are also on view — these, in color, are little Dadaesque billboards.

Walker Evans, Resort Photographer at Work, 1941. Photo: MET

In Resort Photographer at Work from 1941 (printed later, like most his pictures on view from that year), we see a woman “resorter” posing for pictures at the beach with artificial pelicans, palm trees, and a ship’s bow. You can’t help but think of Fellini, as the bleaching light heightens that staged effect.

In a 2022 book on the Florida pictures, the critic David Campany quotes Evans on the purpose of photography:

Valid photography, like humor, seems to be too serious a matter to talk about seriously. If, in a note, it can’t be defined weightily, what it is not can be stated with the utmost finality. It is not the image of Secretary Dulles descending from a plane. It is not cute cats, nor touchdowns, nor nudes; motherhood; arrangements of manufacturers’ products. Under no circumstances is it anything ever anywhere near a beach. In short it is not a lie, a cliche, somebody else’s idea. It is prime vision combined with quality of feeling, no less.

Well, sometimes. When in Florida…

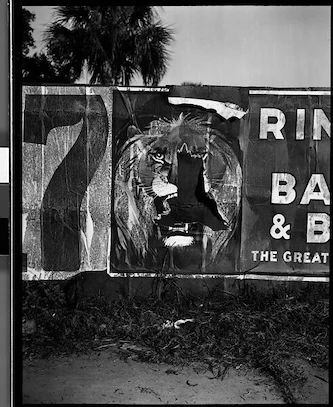

Walker Evans, Torn Ringling Brothers Circus Poster, Florida, 1941. Photo: MET

A selection of Evans’s pictures, entitled Florida, was published by the Getty in 2000, with a wry, snarky text by Robert Plunket, a longtime Sarasota resident. You can find the entire book on the Getty website.

The photographs “present a Florida that doesn’t exist anymore,” Plunket wrote, “and what a strange place it must have been, so foreign looking, so handmade. If they show anything, it is that artificiality is many layers deep. And what better way to illustrate this than with pictures of a small town in Florida where the circus is king, pelicans fill the air, and the people live in little tin houses that they can move from place to place?”

Those “people” were circus folks who spent their off-time in then-sleepy Sarasota, but still lived in decorated structures that evoked their perpetual displacement — homes that seemed to buy into the American home-ownership myth, smaller and far less permanent because they were mobile, yet decorated with real affection.

Evans would return to Florida, and even made paintings of small buildings against the background of sea and sky, as if those structures were flat panels of color and light.

Nature was not crucial for Evans, but it finds its way into Samoylova’s pictures, often in buildings inundated by rain. These were structures that got in nature’s way — a grand metaphor for Florida itself. One example, at the center of the elegiac Abandoned Building on Miami River (2021), is a magnificently decaying ruin. Samoylova’s print of that image, with its abundance of graceful detail, is just as magnificent as the building. It may be no accident that there is an Evans photograph of a place that could be its inspiration, John Ringling Mansion, Ca’d’Zan, Sarasota, Florida, a white elephant of a mansion when Evans observed it in 1941. The structure has somehow remained intact, although it’s closed now for post-hurricane repairs.

In Overpainted Poster, Miami from 2020, Samoylova photographed the head of Donald Trump covered by thick black lines. Was it a stark expression of anger? Perhaps, but don’t rule out homage, either. In 1941 Evans photographed a hole ripped in the glaring face of a tiger in Torn Ringling Brothers Circus Poster, Florida.

Sometimes, despite Evans’s influence, a landscape for Samoylova is just a landscape, albeit a colorful one, an escape into beauty. In Florida these days, landscape (what’s left of it) often stands as an expression of longing; there’s hope against hope that it won’t be paved over as developers and the weather compete to eat up the state. Samoylova reminds us that, for better or worse, freewheeling but steadily decaying Florida is still an American frontier.

Anastasia Samoylova, New Condominium, Bonita Springs, 2021. Photo: MET

For example, in 2021’s New Condominiums, Bonita Springs, two high-rise structures are seen through the haze from a distance as they stand like Mayan ruins in a lush stretch of forest.

You leave the Met show hoping that the grand forest will be there five or 10 years from now, and wishing that Samoylova — or a member of the next generation of gifted photographers — might bring us another glimpse of it.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.