By Lauren Kaufmann

Let’s hope the exhibit inspires some critical thinking about the importance and fragility of democracy, both here and around the world.

Power of The People: Art and Democracy at The Museum of Fine Arts Boston, through February 16, 2025

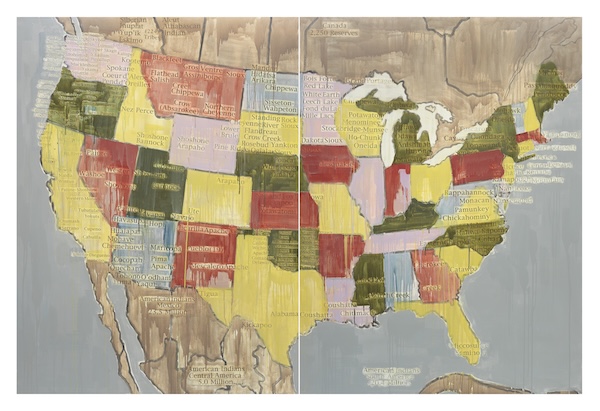

Tribal Map, Jaune Quick‑to‑See Smith, 2000. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Post-election anxiety is prompting many of us to ruminate about democracy. We’re wondering whether it will survive Trump’s second term, and worrying about its waning force around the world. Power of the People: Art and Democracy, a new exhibition at the MFA, addresses some of these issues by offering a sweeping look at democracy.

There are 180 pieces in the exhibition, and the fact that most come from the MFA’s permanent collection tells us a few important things. One is that, for hundreds of years, artists from around the world have expressed their concerns about democracy through their artwork. Another is that the museum has recognized, for a considerable time, the significance of these works by acquiring them. Finally, the variety of media included in the show suggests that artists of all kinds — sculptors, painters, printers, and photographers — have prioritized democracy by focusing on it. The abundance of work sends a strong message. Artists have placed a high value on democracy and the freedoms that go with it — freedom of speech, freedom of expression, freedom of the press, the right to peaceful protest, and the right to participate in political processes.

Vote!, Shepard Fairey, 2008, Poster. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The MFA understands that it needs to remain relevant, timing the exhibition to correspond with election season. Given recent threats against American democracy, the exhibit feels especially timely. The wealth of examples from many centuries ago proves that worries about the health and future of democracy are not new. There are 19th century lithographs exalting freedom of the press, 20th century posters railing against book bans, and anti-war posters designed by students at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts during the Vietnam War.

All this said, the show’s title — Power of the People: Art and Democracy — begs an important question: do artists influence our thinking and political actions through their work? The exhibit doesn’t directly answer the question, but the proliferation of art with a unifying theme indicates that artists believe that they can play a powerful role in our public discourse.

In some cases, we learn about the penalties artists face for freely expressing their views, as in the case of French artist Honoré Victorin Daumier (1808-1879), who was imprisoned for his caricature of King Louis-Philippe. Daumier’s fate brings to mind Trump’s threat to imprison or execute his enemies, including those who speak out against him in the media.

The label for a marble bust of Socrates explains that the ancient Greek philosopher warned that allowing (or even encouraging) citizens to make decisions without having the proper knowledge could lead to dire consequences. Socrates’ concerns were legitimized when, accused of impiety and of corrupting the minds of young people, he was sentenced to death by a jury of 500 fellow Athenians.

The exhibition is organized into three themes: the Promise, the Practice, and the Preservation of Democracy. While the art addresses the trio of themes in a variety of ways there was a telling omission: a definition of the word democracy. It would have been helpful to have the MFA provide its understanding of what the central idea of the exhibition means.

The gallery dedicated to ‘The Promise’ questions some of the problems inevitably generated by a democratic society, exploring the difference between the ideal and the reality. In Lincoln Crushing the Dragon of Rebellion, a small painting by David Gilmour Blythe, dating from 1862, Lincoln faces down a dragon that symbolizes the Confederacy. This work hangs next to a 2021 woodcut by William Evertson, Capitol Offense, in which the artist melds the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol with an image of British troops burning Washington in 1814. Both works demonstrate how democracy can go off the rails when clashes emerge that are driven by minority parties or factions jockeying for power or control.

An arrangement of benches set up in concentric circles occupies the middle of ‘The Promise’ gallery. The configuration is inspired by the ancient Greek bouleuterion, a building where the council met to discuss and vote on public issues. Dating from 500 BCE, the bouleuterion‘s inward-facing seating was designed to encourage conversation. The accompanying label invites museum visitors to take a moment to sit and talk.

Portrait head of Socrates, about A.D. 170–195. Marble from Mt. Pentelikon near Athens. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The gallery dedicated to ‘The Practice’ features artwork that touches on three topics: voting rights, public service, and obstacles to participating in democracy. Tribal Map (2000) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith questions the mechanics of who is represented in our democracy and who is left out. Her map of the U.S. identifies tribes that have been officially recognized by the government. Applications of dripping paint signify Native communities that have vanished while tribal names from the Ohio Valley, where the U.S. government forcibly removed tribes, have been omitted.

Tribal Map is paired with Greasy Grass Premonition #2, by David Paul Bradley, a contemporary Minnesota Chippewa artist. Bradley’s work shows a series of cartoonish images of General George Custer, all viewing a scene in which Native people sit astride their horses while American soldiers have fallen to the ground. The painting tells the story of the battle of Greasy Grass Creek in 1876, also known as Custer’s Last Stand, considered a watershed moment in the history of Indigenous-U.S. relations.

‘The Practice’ gallery also includes a quilt stitched by painter/author Faith Ringgold and her daughter, Michelle Wallace. An image of Martin Luther King, Jr. is at the center, surrounded by smaller portraits of Black female leaders whose contributions have largely been sidelined. Nearby hangs Cyrus E. Dallin’s marble profile of Julia Ward Howe, the famous abolitionist and suffragette, best known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

‘The Preservation’ gallery tackles how artists speak out to maintain democratic principles and call for social change. In a trio of posters made for the Women’s March in January 2017, Shepard Fairey depicts three women, including one wearing a hijab made up of an American flag. Best known for his ‘Hope’ poster designed for Obama’s first presidential campaign, Fairey has played an important role, through his posters, of advocating for progressive change, The gallery includes several works borrowed from the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, founded in Roxbury in 1968. There’s a black-and-white photograph of Huey Newton, leader of the Black Panther Party and a poster of Angela Davis. A series of prints from 2020 address the racial injustice faced by Puerto Ricans. There are a few surprises in this gallery, including a protest coat made by illustrator Saul Steinberg and a photolithograph by sculptor Richard Serra.

Power of the People: Art and Democracy offers a lot to take in, visually and intellectually. Let’s hope the exhibit inspires some critical thinking about the importance and fragility of democracy, both here and around the world.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions. She served as guest curator for Moving Water: From Ancient Innovations to Modern Challenges, currently on view at the Metropolitan Waterworks Museum in Boston.