A mixed bag of counterintuitive results hinders trial interpretation, but experts still see actionable results.

CHICAGO, IL—Adding metformin, a mix of lifestyle and risk factor management (LRFM), or both fails to improve arrhythmia burden over a standard-of-care approach in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who also have implanted cardiac devices, results of the TRIM-AF study show.

The study’s 2×2 factorial-design, inspired by the known impacts of metformin, caloric restriction, and exercise in regulating metabolic stress—itself implicated in AF—produced a mixed bag of findings that left investigators struggling for explanations.

While no differences were seen in the composite primary endpoint of change in AF burden or death for any of the intervention arms, the LRFM groups as well as the standard-care group saw decreases in AF burden over time. LRFM was associated with significant improvements in AF symptom score compared to non-LRFM approaches, and compared with the standard of care; on the other hand, metformin actually looked worse than the standard-care group.

Mina K. Chung, MD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), presented the TRIM-AF data here at the American Heart Association 2024 Scientific Session. Discussing the complex, often counterintuitive results with the media prior to her late-breaking clinical trial presentation, Chung stressed that based on these results, metformin cannot be recommended as an upstream therapy for AF. But, the LRFM findings are worth emphasizing, she added.

Indeed, she said, it may be that the educational materials on lifestyle modification, diet, and exercise provided to patients in the standard-of-care arm—and the discussions those prompted between patients and providers—may have led to meaningful changes that, in turn, reduced AF episodes.

We’re learning that maybe we have more influence over our patients than we sometimes think. Mina K. Chung

“In terms of actionable results, the standard of care decreased AF burden, and I think part of it is that we’re learning that maybe we have more influence over our patients than we sometimes think,” Chung told TCTMD. “We need to actually talk about LRFM and give them instructions, and maybe just that will be helpful.”

Ways of Trimming AF

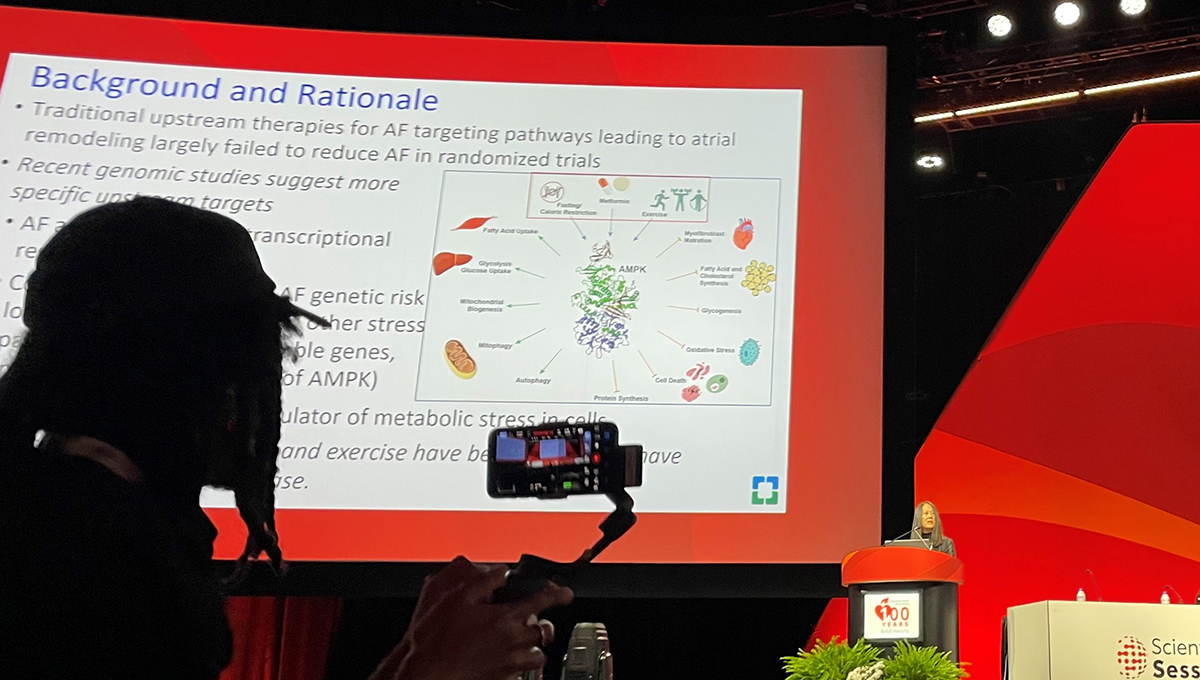

The rationale for TRIM-AF stems from genomic studies suggesting that AF is associated with decreased or impaired responses to metabolic stress that occur as a result of obesity and aging. AMP kinase, a key regulator of metabolic stress, appears to respond beneficially not only to lifestyle and risk factor modifications, but also the diabetes drug metformin.

Researchers intended to enroll 200 patients with documented atrial fibrillation who also had implanted pacemakers or ICDs with atrial leads that could measure both AF and activity levels over follow-up. Target enrollment was reduced to 149 as a result of the COVID pandemic.

As Chung showed here, the trial opened with a 3-month blanking period to allow for metformin to be uptitrated to 750 mg twice a day. Thereafter, however, the data that rolled in between months 3 and 12 went in numerous, unexpected directions. For one, all of the intervention groups lost weight, but none significantly increased their exercise capacity. For another, the standard-of-care group actually lowered their AF burden, which is unusual for the natural course of the disease.

What we have in the clinical guidelines from 2023 still stands and many of the targets put forth by the guideline is still relevant. Janice Chyou

LRFM improved AF burden, as expected, but metformin went in the wrong direction. One explanation, said Chung, is that the benefits of LRFM and metformin are similar, but not additive, so that the combination was no better than either alone. Metformin’s performance, too, might have been blunted by two deaths that occurred in this group prior to either patient even starting the drug, as well as by problems with drug adherence. By 1 year, nearly half of the patients in the metformin-only arm and one-quarter of the patients in the combination arm had discontinued their medications.

“At this time,” Chung told TCTMD, “we probably shouldn’t be using metformin for primary prevention, for upstream therapy for AF, until we learn a little more. And we don’t know about some of the other agents out there, like SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs. Metformin was what we had available at the time we started this study.”

‘Still Relevant’

Commenting on the trial for the media, Janice Chyou, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), hailed TRIM-AF as “interesting, relevant, and important . . . because unlike many of the studies that we see, this is informed by transitional insights,” specifically, the identification of AMP kinase signaling. The study also rests on a foundation of pharmacoepidemiologic research supporting the use of metformin in this setting, she said.

What’s not clear, Chyou continued, is whether patients with implanted devices and AF were the appropriate patient group for a study seeking to uncouple AF from cell stress. Patients with heart failure, for example, might have different AF triggers and pathology less likely to respond to metformin and LRFM.

As such, “this study contributes to the body of supported evidence that LRFM in patients with atrial fibrillation is important. . . . We look forward to further thoughts and more analysis to understand if there may be specific A-fib patients who may still benefit from metformin for a future study,” Chyou concluded.

To TCTMD, Chyou agreed there is still “actionable” information from this otherwise neutral trial. “I think the fact that this reinforces the importance of lifestyle risk factor modification is key. . . . What we have in the clinical guidelines from 2023 still stands, and many of the targets put forth by the guideline is still relevant,” she stressed.