Abstract

Background

Frailty and protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) are common in older home care clients. In this study, we evaluate the effect of individually tailored dietary counseling on frailty status among home care clients with PEM or its risk aged 75 or older with a follow-up of six months.

Methods

This intervention study is part of the non-randomized population-based Nutrition, Oral Health and Medication (NutOrMed) study in Finland. The frailty was assessed using the abbreviated Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (aCGA) and included 15 questions from three different domains: cognitive status (MMSE), functional status (ADL, IADL) and depression (GDS-15). The study population consisted of persons with PEM or its risk (intervention group n = 90, control group n = 55). PEM or its risk was defined by MNA score <24 and/or plasma albumin <35 g/l. Registered nutritionist gave individually tailored nutritional counseling for participants at the baseline and nutritional treatment included conventional food items.

Results

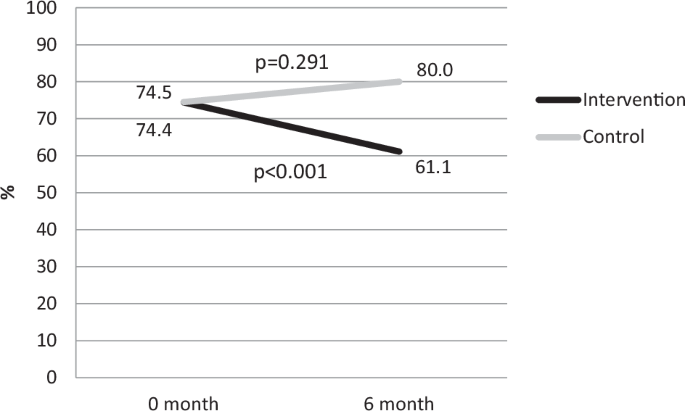

The mean age was 83.9 in the intervention and 84.3 in the control group. At the baseline frailty prevalence was 74.4% (n = 67) and after six-month 61.1% (n = 55) in the intervention group and, respectively 74.5% (n = 41) and 80.0% (n = 44) in the control group. The intervention decreased significantly (p < 0.001) the prevalence of frailty in the intervention group, while it increased in the control group.

Conclusions

Individually tailored nutritional counseling reduces the prevalence of frailty among vulnerable home care clients with PEM or its risk. In the nutritional treatment of frailty, adequate intake of protein and energy should be a cornerstone of treatment.

Introduction

Frailty is a syndrome commonly found in older people [1], characterized by reduced physiological resources and resilience to stressors [2]. This geriatric condition makes older people more susceptible to adverse health effects and increases the risk of functional inability, immobility, falls, loneliness, social isolation, disability, hospitalization, institutionalization, mortality [1,2,3,4], and healthcare costs [5]. The prevalence of frailty among older home care clients ranges from 41.5 to 90% [6,7,8].

Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) is also a significant problem among older people [9, 10]. PEM is a form of malnutrition when the protein and energy intake do not meet the nutritional requirements [11]. Frailty and PEM are closely linked, with each having an impact on the other [12, 13]. Frail individuals are more likely to have PEM, and PEM increases the risk of frailty and the negative outcomes associated with it [6, 14, 15]. However, frailty and PEM are potentially reversible situations, so there is a need for clinical interventions focusing on treating PEM and investigating whether it affects frailty status.

In our previous study, we found that it is possible to improve the nutritional status of older home care clients by providing individually tailored nutritional counseling that takes into account their eating preferences [16]. However, we have little knowledge about the effect of nutritional intervention on frailty status. Therefore, we aimed to study the effect of individually tailored dietary counseling on frailty status among home care clients aged 75 years or over with PEM or at risk of it with a follow-up of six months.

Methods

Design and participants

This intervention study is a part of the population-based multidisciplinary Nutrition, Oral Health and Medication study (NutOrMed study), which aimed to evaluate and improve the nutritional status, oral health, and functional ability of older home care clients in three cities in Eastern and Central Finland [17]. A detailed description of the NutOrMed study and its design is described in the previous article [17]. In Finland, municipalities and private organizations offer home care services, including home help, nursing, management of medications, and medical care.

This study included a subpopulation of home care clients with PEM or its risk. The intervention group included 90 participants, and the control group 55 participants. To prevent any potential influence, the intervention group was located approximately 100 km away from the towns of the control groups. There were no exclusion criteria based on morbidity or cognitive status. All the participants were able to eat normal food items. If a participant was unable to reply, typically due to cognitive impairment, the data collection was supplemented by a caregiver or home care nurse.

Measurements

Frailty was assessed using the abbreviated Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (aCGA), which includes three questions on Activities of Daily Living (ADL), four questions on Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), four questions on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), and four questions on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) [18]. According aCGA frailty was defined when the cut-off value was exceeded in at least two domains (function ability, cognitive symptoms, depressive symptoms) on the aCGA (Supplementary Table 1). The cut-off value for function ability (ADL, IADL) was ≥1, for cognitive symptoms (MMSE), ≤6, and for depressive symptoms (GDS-15) ≥ 2. The validated aCGA is designed to identify frailty in vulnerable individuals and it can detect problems in daily living such as difficulties in bathing, dressing and shopping as well as declined cognition or depressive symptoms [18]. The participants’ nutritional status was assessed using a Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) by a clinical nutritionist. The MNA is a validated and standardized tool for detecting the nutritional status of older people [19,20,21,22]. Both PEM and the risk of PEM were defined as a score of less than 24 on the MNA and/or plasma albumin less than 35 g/l [18].

Drug use was defined as regular and as-needed use of prescription and over-the-counter drugs. Polypharmacy was defined as the use of 10 or more drugs regularly or as needed [23]. Oral health was evaluated by a dental hygienist. The feeling of dry mouth was assessed by asking the participants if they had experienced it, and the responses were categorized as none, occasionally or continuously. Chewing problems were evaluated with the question “Do you have chewing problems?” with the answer options being “yes” or “no”.

The information on cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, asthma/COPD, stroke, visual or hearing impairment, and depressive symptoms was obtained from electronic medical records based on a clinical diagnosis. More comorbidities were defined by the Functional Comorbidity Index (FCI) (including 13 diseases) based on health records [24]. The diagnosis of any disorder, including cognitive disorder, was verified by a geriatrician through medical records. Functional ability was assessed using the ADL [25] scale, with a cutoff score of <80, and the IADL [26] scale, with a cutoff score of ≤4. Cognition was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [27], with a cutoff score of ≤24. The ability to walk 400 meters was self-reported by the participants, with categories ranging from unable to walk to able to walk independently with or without difficulties. Participants were asked to rate their current health status into two categories: quite good and good, or average, quite bad, and bad. Demographic data was also collected at baseline. All measurements were taken at baseline and after a six-month follow-up, except for drug use and comorbidities, which were only evaluated at baseline. In cases where participants were unable to respond, data was supplemented by a caregiver or nurse. More details of the measurements have been described in a previous study [17].

Intervention

The nutritional intervention was based on the results of the baseline MNA test, plasma albumin, and a 24-h dietary recall. For the intervention group, a clinical nutritionist provided one individualized nutritional guidance based on the 24-h dietary recall and planned individualized nutritional care during the same visit, in collaboration with the client and their nurse or family members. The nutritional care plan was based on international recommendations for protein intake [28] and national nutrition recommendations for older persons [29]. The goal for protein intake was 1 g/kg, and energy intake was 125,6 kJ/kg per day. The intervention aimed to increase the intake of energy-dense foods, meals, and protein- and nutrient-rich snacks with normal food items. While a vitamin D supplement was recommended, it was not included in the analysis, and no multivitamin supplements were prescribed. In case the participant had cognitive decline or other reasons why he/she had difficulties understanding, remembering, or following up, nutritional counseling was carried out in close cooperation with the home care nurse or caregiver. The control group did not receive any nutritional guidance. More details of the nutritional intervention have been described in a previous study [30]. The effects of the intervention were monitored after six months follow-up in both study groups.

Statistical analysis

Group characteristics were compared using independent samples t test (normally distributed outcomes) or Pearson’s Chi-square test as appropriate. The normality of variables was checked with Shapiro–Wilk’s test. To compare the effect of the intervention between the groups, a generalized estimation equations model analysis was adopted, which was adjusted for age, gender, education years, and cognitive decline. Improvements in frailty status and protein and energy intake during the intervention were analyzed using a mixed-effect regression model. Participants assessed at baseline and after six months were included in the data analysis (per protocol). Any p value less than 0.05 was statistically significant. The data was analyzed using SPSS 27.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

The study involved participants with a mean age of 83.9 years, with 72.2% of them being female in the intervention group, and 84.3 years and 63.6% in the control group respectively (Table 1). The intervention group had more years of education and a greater intake of energy (kJ/kg/d) and protein (g/kg/day), as well as more frequent excessive polypharmacy and strokes, and lower FCI and cognition compared to the control group. After the intervention, the intervention group had a higher MNA score and less PEM or its risk, as well as a greater intake of energy (kJ/kg/d) and protein (g/kg/day), and more participants were able to walk 400 meters compared to the control group.

At baseline, the prevalence of frailty in the intervention and control groups did not differ (p = 0.847). At baseline, in the intervention group, the prevalence of frailty was 74.4% (n = 67), and after six months, it decreased significantly to 61.1% (n = 55) (p < 0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 1). In the control group, the prevalence of frailty increased from 74.5% (n = 41) to 80.0% (n = 44) (p = 0.291). After the intervention, there was a significant difference in the prevalence of frailty between the study groups (p = 0.047). Furthermore, the higher protein (g/kg/d) and energy (kJ/kg/d) intake of the intervention group were significantly associated with the decrease in frailty status when adjusted by age, sex, education, excessive polypharmacy, and FCI (p = 0.009 and p = 0.023, respectively). Additionally, the prevalence of depressive symptoms domain of aCGA decreased during the study in both groups (Table 2).

Panel 0 month represents the baseline data, and panel 6 month represents the follow-up data. p < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference within the same group over time.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the effects of individually tailored nutritional counseling on persons with PEM and frailty, including common problems in cognition, functional abilities, and unable to take care of themselves including their nutrition. We found that individual nutritional counseling, which focused on increasing protein and energy intake while considering individual dietary preferences, was associated with a decrease in frailty status among older home care clients with PEM or its risk. Our findings are consistent with previous research indicating that higher protein intake is inversely associated with frailty in older adults [31, 32]. Nutritional status is crucial to all frailty criteria [2], and a higher protein intake can slow down the decline of muscle mass, walking speed, and weight loss [33]. Among frail older persons, higher protein intake is associated with better muscle mass and physical performance, which can improve function ability [33, 34]. Moreover, our study found that energy intake is also associated with a decrease in frailty. Adequate dietary energy is essential for protein to effectively stimulate muscle protein synthesis and prevent muscle mass loss [35]. Therefore, our findings suggest that both protein and energy intake are critical for reducing frailty among older people, as supported by previous research [32, 36, 37].

It seems, that dietary intervention targeting sufficient protein and energy intake can have an impact on other symptoms, including a decrease in depressive symptoms according to the aCGA. This could be due to increased social interaction related to nutrition, which is supported by previous studies that have shown improved quality of life, self-rated health, cognitive function, and fewer depressive symptoms as a result of nutrition intervention [38, 39]. Furthermore, our findings indicate that ensuring adequate protein and energy intake is a viable strategy for preventing and reducing frailty in older people, even in vulnerable populations receiving home care. Since frailty and PEM are closely associated [13], treating PEM and improving nutritional status [16] can explain the reduction in frailty among participants in the intervention group.

Strengths of our study include its real-life intervention among home care clients, without any exclusion criteria. The study’s multidisciplinary approach and use of validated instruments also contributed to its value. Additionally, the individually tailored nutritional intervention based on participants’ preferences likely enhanced its effectiveness and acceptance. Furthermore, the nutrition intervention was administered by the same registered nutritionist, which enhanced reliability. We collected comprehensive data on nutrient intake using the 24-h recall method, administered by a registered nutritionist, and the information on cognitive decline was obtained from medical records, family caretakers, and homecare nurses. The study’s limitation was the short follow-up of only six months. However, home care clients’ health status is often unstable, and a longer follow-up could have resulted in a higher loss of participants.

Conclusion

An individual-tailored nutritional intervention can decrease the prevalence of frailty status among vulnerable home care clients with PEM or its risk. In the nutritional treatment of frailty, adequate intake of protein and energy should be a cornerstone of treatment. By addressing individual nutritional needs, we can help vulnerable home care clients improve their quality of life and overall health.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to limitations of ethical approval involving the patient data and anonymity but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Clegg A, Young J, Ilife S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–62.

Google Scholar

-

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–156.

Google Scholar

-

Vermeiren S, Vella-Azzopardi R, Beckwée D, Habbig AK, Scafoglieri A, Jansen B, et al. Frailty and the prediction of negative health outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:1163.e1–e17.

Google Scholar

-

Portegijs E, Rantakokko M, Viljanen A, Sipilä S, Rantanen T. Is frailty associated with life-space mobility and perceived autonomy in participation outdoors? A longitudinal study. Age Ageing. 2016;45:550–3.

Google Scholar

-

Hajek A, Bock JO, Saum KU, Matschinger H, Brenner H, Holleczek B, et al. Frailty and healthcare costs-longitudinal results of a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2018;47:233–41.

Google Scholar

-

Miettinen M, Tiihonen M, Hartikainen S, Nykänen I. Prevalence and risk factors of frailty among home care clients. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:266.

Google Scholar

-

Shirai S, Kwak MJ, Lee J. Measures of frailty in homebound older adults. South Med J. 2022;115:276–9.

Google Scholar

-

Kelly S, O’Brien I, Smuts K, O’Sullivan M, Warters A. Prevalence of frailty among community dwelling older adults in receipt of low level home support: a cross-sectional analysis of the North Dublin Cohort. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:1–11.

Google Scholar

-

Crichton M, Craven D, Mackay H, Marx W, de van der Schueren M, Marshall S. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition: associations with geographical region and sex. Age Ageing. 2019;48:38–48.

Google Scholar

-

Scholes G. Protein-energy malnutrition in older Australians: a narrative review of the prevalence, causes and consequences of malnutrition, and strategies for prevention. Health Promot J Austr. 2022;33:187–93.

Google Scholar

-

Mathewson SL, Azevedo PS, Gordon AL, Phillips BE, Greig CA. Overcoming protein-energy malnutrition in older adults in the residential care setting: a narrative review of causes and interventions. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;70:101401.

Google Scholar

-

Roberts S, Collins P, Rattray M. Identifying and managing malnutrition, frailty and sarcopenia in the community: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2021;13:2316.

Google Scholar

-

Dwyer JT, Gahche JJ, Weiler M, Arensberg MB. Screening community-living older adults for protein energy malnutrition and frailty: update and next steps. J Community Health. 2020;45:640–60.

Google Scholar

-

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Woo J. Nutritional interventions to prevent and treat frailty. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2019;22:191–5.

Google Scholar

-

Gabrovec B, Veninšek G, Samaniego LL, Carriazo AM, Antoniadou E, Jelenc M. The role of nutrition in ageing: a narrative review from the perspective of the European joint action on frailty – ADVANTAGE JA. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;56:26–32.

Google Scholar

-

Pölönen S, Tiihonen M, Hartikainen S, Nykänen I. Individually tailored dietary counseling among old home care clients – effects on nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21:567–72.

Google Scholar

-

Tiihonen M, Autonen-Honkonen K, Ahonen R, Komulainen K, Suominen L, Hartikainen S. NutOrMed—optimising nutrition, oral health and medication for older home care clients—study protocol. BMC Nutr. 2015;1:13.

Google Scholar

-

Overcash JA, Beckstead J, Extermann M, Cobb S. The abbreviated comprehensive geriatric assessment (aCGA): a retrospective analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;54:129–36.

Google Scholar

-

Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: the Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev. 1996;54:S59–65.

Google Scholar

-

Guigoz Y, Lauque S, Vellas BJ. Identifying the elderly at risk for malnutrition. The mini nutritional assessment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:737–57.

Google Scholar

-

Soini H, Routasalo P, Lagström H. Characteristics of the mini-nutritional assessment in elderly home-care patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:64–70.

Google Scholar

-

Vellas B, Guigoz Y, Garry PJ, Nourhashemi F, Bennahum D, Lauque S, et al. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition. 1999;15:116–22.

Google Scholar

-

Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:514–22.

Google Scholar

-

Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, Wright JG. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:595–602.

Google Scholar

-

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65.

Google Scholar

-

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186.

Google Scholar

-

Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini-mental state: a practical method of grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Google Scholar

-

Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, Cruz-Jentoft A, Goisser S, Hooper L, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:10–47.

Google Scholar

-

Finnish institute for health and welfare. Vitality in later years: food recommendation for older adults. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare THL. 2020. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-517-9. Assessed 15 March 2024.

-

Kaipainen T, Hartikainen S, Tiihonen M, Nykänen I. Effect of individually tailored nutritional counselling on protein and energy intake among older people receiving home care at risk of or having malnutrition: a non-randomised intervention study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:391.

Google Scholar

-

Coelho-Júnior HJ, Rodrigues B, Uchida M, Marzetti E. Low protein intake is associated with frailty in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2018;10:1334.

Google Scholar

-

Lorenzo-López L, Maseda A, de Labra C, Regueiro-Folgueira L, Rodríguez-Villamil JL, Millán-Calenti JC. Nutritional determinants of frailty in older adults: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:108.

Google Scholar

-

Mendonça N, Granic A, Hill TR, Siervo M, Mathers JC, Kingston A, et al. Protein intake and disability trajectories in very old adults: the newcastle 85+ study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:50–56.

Google Scholar

-

Park Y, Choi JE, Hwang HS. Protein supplementation improves muscle mass and physical performance in undernourished prefrail and frail elderly subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108:1026–1033.

Google Scholar

-

Carbone JW, McClung JP, Pasiakos SM. Recent advances in the characterization of skeletal muscle and whole-body protein responses to dietary protein and exercise during negative energy balance. Adv Nutr. 2018;10:70–79.

Google Scholar

-

Bartali B, Frongillo EA, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Semba RD, Fried LP, et al. Low nutrient intake is an essential component of frailty in older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:589–93.

Google Scholar

-

Artaza-Artabe I, Sáez-López P, Sánchez-Hernández N, Fernández-Gutierrez N, Malafarina V. The relationship between nutrition and frailty: effects of protein intake, nutritional supplementation, vitamin D and exercise on muscle metabolism in the elderly. A systematic review. Maturitas. 2016;93:89–99.

Google Scholar

-

Blondal BS, Geirsdottir OG, Halldorsson TI, Beck AM, Jonsson PV, Ramel A. HOMEFOOD randomised trial – Six-month nutrition therapy improves quality of life, self-rated health, cognitive function, and depression in older adults after hospital discharge. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2022;48:74–81.

Google Scholar

-

Endevelt R, Lemberger J, Bregman J, Kowen G, Berger-Fecht I, Lander H, et al. Intensive dietary Intervention by a dietitian as a case manager among community dwelling older adults: the EDITstudy. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:624–630.

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the staff involved in this study for their positive attitude during the data collection.

Funding

Data collection was supported by The Northern Savo Regional Fund. The writing of this article was supported by The Northern Savo Regional Fund. Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (including Kuopio University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This substudy was designed by T.K., S.H., and I.N. T.K. and I.N. performed analysis and interpretation of data. T.K. drafted the manuscript. S.H., I.N., and M.T. contributed to the writing and critical appraisal of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District, Kuopio, Finland. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplemental Table 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaipainen, T., Hartikainen, S., Tiihonen, M. et al. Effect of individually tailored nutritional counseling on frailty status in older adults with protein-energy malnutrition or risk of it: an intervention study among home care clients.

Eur J Clin Nutr (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01547-0

-

Received: 14 May 2024

-

Revised: 08 November 2024

-

Accepted: 13 November 2024

-

Published: 23 November 2024

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01547-0