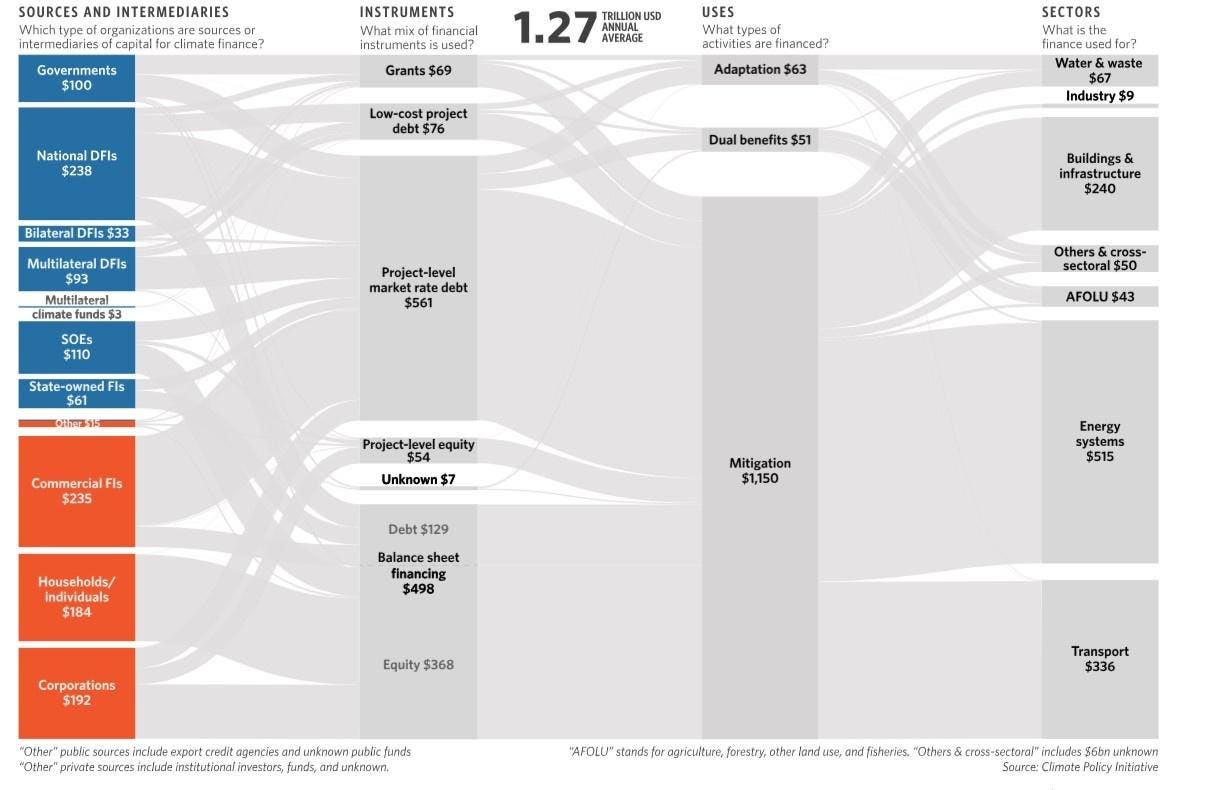

The deal which was finally reached at COP29 in Baku for a $300 billion investment for climate change finance for developing countries reflects a zero-sum game of donor funds. This is far short of the $1.3 trillion annual commitment for a full portfolio of transitioning to renewable energy technologies, climate adaptation infrastructure and loss compensation over climate-related events that was being sought. The developing countries had arrived at this number based on a range of estimates for meeting their “Nationally Determined Contributions” under the Paris Agreement. The United Nations itself has estimated the needed contributions needed for developing countries to mitigate, adapt and be compensated for damages at around $1.55 trillion per year.

The elephant in the room at the final COP29 meeting was the global military industrial complex. Expenditure on defense is of course the easiest comparable target by activists in terms of political priorities that have been set forth by the world. In 2023, the global military expenditure was estimated to be around $2.24 trillion of which the United States constituted more than $800 billion (more than the sum of the next 10 countries combined). The climate finance goal set forth by developing countries was only 60% of this expense. While we are on the topic of trillion-dollar tradeoffs, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy have also set a target for cutting around $2 trillion from the U.S. government’s total annual expenditure of $6.75 trillion. The new “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) should, however, consider that the International Chamber of Commerce has estimated that extreme weather events cost the global economy also around $2 trillion. These are estimates of actual costs incurred and not forecasts and offer a sobering reminder that ignoring the primacy of natural systems can have a direct financial cost on us all as well.

There may be a way to link climate finance to Musk and Ramaswamy’s cost-cutting through DOGE by pragmatic argumentation. In a new book, called Threat Multiplier: Climate, Military Leadership and the Threat to Global Security, America’s first deputy undersecretary of defense for environmental security Sheri Goodman, provides valuable insights on the role of science and technology in the “greening” of the U.S. Military’s culture. This was not a case of “Woke ESG greening” by making electric tanks or switching to a more vegetarian diet for soldiers, but win-win strategies like more efficient flight plans and material reuse and recycling by the military. Such strategies might even be embraced by Pete Hegseth (President Trump’s embattled nominee for Defense secretary) as a way of making the military leaner and more efficient.

Goodman recounts how the creation of the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) by Senators Sam Nunn and Senator Al Gore in 1990 with just $25 million in federal funding. Much of the impetus for such efforts came from a recognition of a cleanup after the Cold War. A vital environmental agreement was achieved in 1996 with the Russians regarding cleanup of damage from their ageing submarine fleet. Climate change was then a peripheral part of the environmental security conversation, but this soon changed and through pragmatic arguments, Goodman changed the way the generals thought of climate change.

Militaries are not only massive consumers of precious public funds; they are also major consumers of fossil fuels. Any curtailment of this demand to reduce carbon emissions was initially perceived by the American military as a perilous intrusion by policymakers. However, as revealed in Threat Multiplier, bold leadership by a few lawmakers and bureaucrats in the U.S. government changed this perception to a point where “climate security” has become an accepted concept within the Pentagon. Key to Goodman’s success in developing trust between scientists and the military’s top brass was to communicate within a lexicon that they could embrace.

While civilian decision-makers are often less prepared to make decisions on low probability events of high impact, the military is trained to plan for exactly such events like a nuclear strike. Quoting General Sullivan at one meeting, she recounts him saying: “If you wait until you have one hundred percent certainty, something bad is going to happen on the battlefield.” Unlike the public or the civilian leadership, “uncertainty was not crippling. In fact, it was the very uncertainty of climate change that created urgency for action.” Such a pragmatic Bayesian approach to decision-making on climate investments may well be appealing to Musk and Ramasawamy at DOGE as well. The case for redirecting even a small portion of savings from military expenditures to climate finance is quite robust, as argued as well by Oxford political scientist Neta Crawford in her book titled The Pentagon, Climate Change and War which won the Grawemeyer Award for Ideas that Improve World Order.

By speaking the decision-risk lingo of the military, Goodman convinced the generals to consider climate change as a risk with higher probability and potentially higher consequences as well. The name of the book also stems from an epiphany that struck Goodman as she red military literature and came across the term “force multiplier” to signify factors that enable the military to accomplish cumulatively greater feats of action. A GPS device is an example of a “force multiplier technology. Hence, she considered the term “threat multiplier” as a way to describe climate change. Existing threats of ethnic conflict or myriad other security challenges would be accentuated by climate change.

Goodman’s coining of the term “threat multiplier” to describe the security implications of climate change has stuck well across national and international policy domains. This term is noted in the Climate Change Security Oversight Act of 2007, the Lieberman-Warner Climate Security Act of 2008 and the Clean Energy Security Act of 2009. In addition to U.S. policy transformation, Goodman’s work also resonated with the United Nations Security Council when the first resolution to consider climate change was passed in 2007. The impact of such an approach has led even the CEO of Exxon Mobil, which is a clear beneficiary of the Military Industrial Complex, to urge President Trump to remain in the Paris Agreement. Major defense contractors such as Lockheed Martin have already committed to climate mitigation as well.

Climate finance should be considered as a way of galvanizing efficiency rather than as a cost sink. Despite modest progress on the initial goals set forth by developing countries, the deal at COP29 is moving the world closer to seeing win-win opportunities of decarbonization of key industrial sectors. While we should always be wary of any “rebound effects” in higher resource consumption of efficiency programs, there is a good case for DOGE, to consider carbon mitigation as a means diagnosing cost excesses in the government. In addition to running emission mitigation efforts through Tesla, Elon Musk has shown leadership on decarbonization technologies through his philanthropic investment in the $100 million Musk Foundation X prize for carbon removal. This shows that he can see the value of smart investments as part of a broader efficiency regime, while also considering new frontier investments in nuclear energy that were agreed upon in COP28, and are part of a bipartisan consensus in Washington.

Of the total estimated climate finance flows of around $1.3 trillion, the injection of an additional $300 billion that has been agreed upon for developing countries should be possible to achieve through smart efficiency measures. Investment in adaptation as well as loss and damage, will need to rise considerably as it is now becoming clear that mitigation alone will simply not meet timelines for crucial tipping points. In the long run such investments will also end up saving on insurance premiums, disruptions to manufacturing and services and making the global economy more resilient. COP29 may have not been an optimal outcome for meeting climate finance goals but there are important opportunities for leveraging what has been achieved in the final deal.