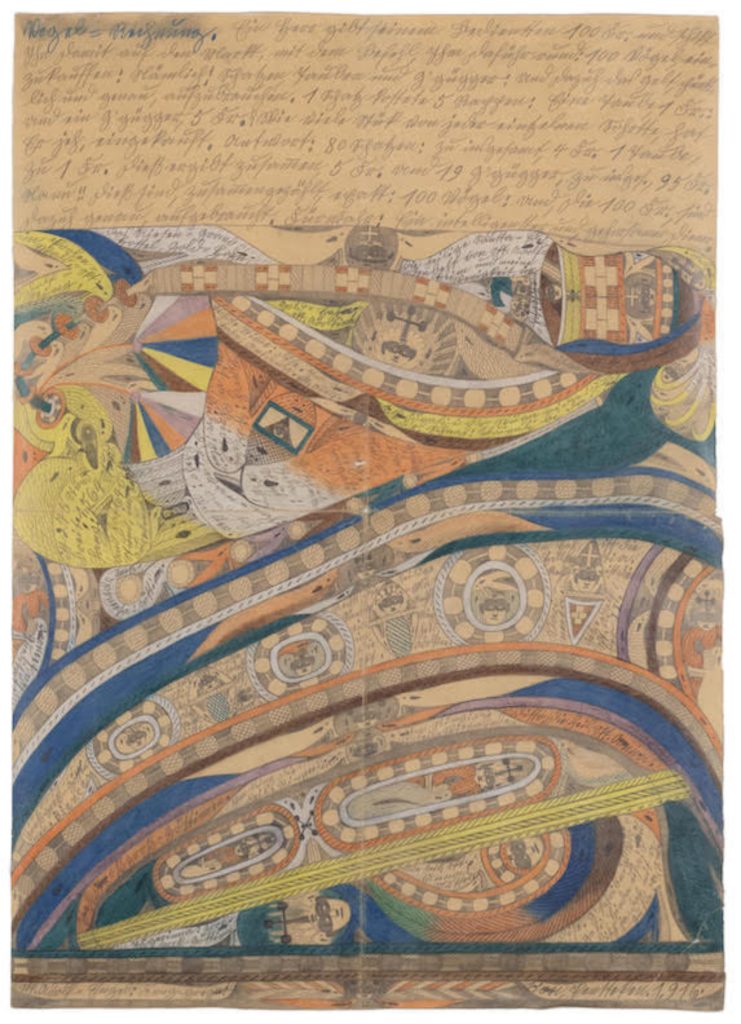

Adolf Wolfli, “Blatt aus Heft no. 13,” c. 1916, graphice and colored pencil on paper, 39″ x 28″/Photo: The Drawing Center, New York

It can be unnerving to see the work of my beloved Chicago Imagists far outside of Chicago. Maybe it’s because their paintings just aren’t the same when you’re not primed by that distinctly Midwestern banality, which gives teeth to their visual hedonism. Or maybe I’m longing again for the sense that I’ve discovered a hidden gem, privy only to a select few. Whatever reservations I once had about Imagist art being exported outside the Midwest have been shattered by the Drawing Center’s current show, which draws over 300 works on paper from the collection of graffitist-turned-mega-artist Kaws.

The exhibit is centered around two re-creations of Kaws’ studio, where artsy furniture is backgrounded by cavalcades of visual stimulation. Giants are hung next to giants: the asemic sheet music of Adolf Wölfli by the obsessively-limned cowboys of Martín Ramírez; Joyce Pensato’s destructive Mickey Mouses by Raymond Pettibon’s risible anecdotes; Peter Saul by R. Crumb; Louis Wain by Dana Schutz. It’s a lot to take in. The two central walls would be overwhelming were it not for the three H.C. Westermann sculptures that stand like idiot-prophets in front of each wall, taking them in. Especially endearing are “Swingin’ Red King” and “The Silver Queen,” who stand befuddled in front of a star-studded wall like mutated clusters of household fixtures. Westermann’s peculiar charm—which arises from his discovery of élan vital in objects and materials of suburban amusement—is on full display in these clueless dilettantes.

Lesser known than Westermann’s hermetic sculptures are his works on paper, six of which are on display here. (Magnificent as the works on paper are, they also reveal Westermann to be less of an autodidact than he’s often portrayed—the influence of fellow Imagist Jim Nutt on his figures is undeniable.) His men are slender and stately, his women imperiled and curvaceous. I can see no better expression of his career than “In the Desert,” where a nude woman glances disconcertedly at a yowling hyena—Westermann is that noisy predator, calling out his innermost self without care for whether or not anyone will hear.

Helen Rae, “Untitled (February 2, 2010),” 2010, color pencil and graphite on paper, 24″ x 18″/Photo: The Drawing Center

For the show’s everything-all-at-once center, one of its dimly lit corners is the site of a holy icon: a full sheet of drawings by Henry Darger from his 10,000+ page story “In the Realms of the Unreal.” Here, his protagonists are seen only by silhouette: the seven heroic Vivian girls, toddlers fighting against the godless Glandelinians to end child slavery, hide from approaching soldiers in a bleak cavern. Darger’s quirks are all on full view: the way his pastel-colored caves seem to be made of flat sheets of paper, for instance, or his tendency to paint outside of his forms’ graphite outlines. The Vivian girls are rendered with bursting tenderness, hobbling about with the unsteady gait of tykes in the mid-single digits. It couldn’t be clearer by looking that Darger lived for his art, that in a sense it was his life—lacking a vessel for his affection in his day-to-day activities, he made one up. And what joy that he wrote the tale down for our pleasure. Go, witness this love like no other.

Dotted throughout the show are masterworks of the less-eccentric Imagists. Karl Wirsum is represented by an E.T.-like sculpture and a study for his “Show Girl” series, in which an ample red-skinned woman sprouts the jagged cactus-like edges characteristic of his oeuvre. Power couple Jim Nutt and Gladys Nilsson are also featured, each working in their typical style—Nutt drawing his jagged-faced goofballs, Nilsson her watercolor scenes of phantasmagoric carousal. The show’s Chicagoans do our city well, losing none of their visual pop next to New York analogues like Peter Saul and Helen Rae. Does this show signify the start of a new cultural moment, one in which the provincial Midwest grows closer to the capital? Who knows. We’ll be patiently waiting to find out.

“The Way I See It: Selections from the Kaws Collection” is on view at The Drawing Center, 35 Wooster Street, New York, through January 19, 2025.