When Denver artist Tim McKay was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease last year, he made a quick decision: He would document the progression of his disease through his art. He immediately started a project he called “One to Somewhere,” creating as many paintings as he could over the next 12 months.

Now complete, his “visual journal,” as he calls it, went on display on Nov. 29 at Pirate Contemporary Art in Lakewood.

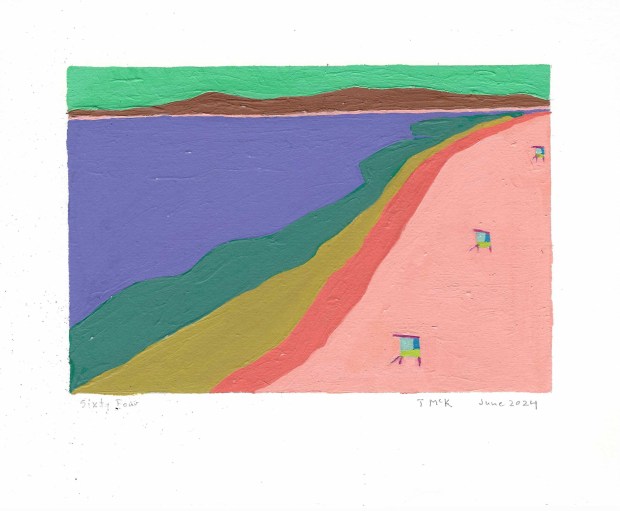

The 77-work series is rendered in acrylic paint, mostly on small pieces of paper, and combines both abstract, geometric patterns and representational scenes conjured from his memory.

Each painting is rich in color and full of mystery, though brought together they evoke a very personal tale of living with an illness that robs, on its own schedule, the ability to control the way our bodies behave.

We asked McKay to tell us the story behind the project.

Q. Can you give us a little background on your painting?

A. I started painting seriously about 20 years ago after my partner, tired of hearing that I was going to “paint someday,” signed me up for an introductory acrylics class with Michael Gadlin at the Art Student’s League of Denver. Michael and I clicked and I found I loved to paint abstractly. I began a practice focused on color — a visual representation of expressed and experienced feelings. In the last eight years, my work has become more structural and geometric, although that is changing now, and I occasionally work in mixed media and ceramics. I primarily work from a home studio of about 90 square feet. Small but mighty; every inch is accounted for.

Q. When did you learn you had Parkinson’s disease?

A. I was formally diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (PD) a little over a year ago, September 2023. It was hard to hear but not a complete surprise. I have had neurological symptoms for about 20 years but even after spending a week at Mayo Clinic, I was not definitively diagnosed and I eventually plateaued.

In early 2023, I saw a neurologist after not seeing one for nine years. My main concern was with increases in nerve pain, but the neurologist saw problems with my movement and balance as well. After continued symptom progression and a positive response to PD medications, a diagnosis was made. Initially I felt a bit of relief, but then the realities of having an active, progressive disease with no defined endpoint of disability began to hit.

It’s a disease that requires continual mental and physical adjustments in order to live life well.

Q. You processed it, at least partly, through your art. How did you decide to start this project?

A. Processing is ongoing and I don’t think it ever stops given the nature of a progressive disease with many difficult endpoints. A joke, so to speak, that most every PD patient will hear is: The good news is Parkinson’s won’t kill you. The bad news is Parkinson’s won’t kill you. Every day is different and challenging, and a PD diagnosis leaves no clean path for how life will unfold.

It’s that feeling I wanted to capture. Could I do a project that was an honest reflection of my coming to grips with living life in a very different way? How would that show in my art? How would my art change with more motor problems?

Originally, this was just a personal project. I was months into it before considering sharing it publicly.

Q. You chose an interesting format, mostly 7 by 8.5 inch works on paper, painted in acrylic.

A. It was somewhat arbitrary, but I wanted the paper to be the same size to make comparing pictures easier. Small works on paper are also easier to store. I like the feel of paper. And saw it as a medium to get more work done faster.

For each painting, I drew a ½ grid, leaving a margin. The grid helps with the sizing of geometric forms. The only other “rules” I had for myself were to paint whatever I wanted and to finish every work begun. I valued immediacy and honesty over precision and refinement.

Q. So, what were you painting? Looking through the works, many pieces read like pure geometric abstraction. Others look representational?

A. I like working geometrically. It is a great vehicle for containing and manipulating color as well as providing a framework for storytelling. The format is flexible enough so works can skew toward being more emotional or cognitive.

The representational works have been a surprise, based on memories of growing up in Santa Monica, Calif. I painted these as “encounter planes” — highlighting specific objects, minimizing the “noise” around them, then combining encounters into a single composition that feels flat but has some perspective.

Q. I think the difficult question here is how your health influenced the work. But let’s start with the physicality of it. Did painting become more demanding over time, and how did you accommodate that?

A. As an artist, I have made continuous small changes in my practice. I work more slowly. Control is more possible when movements are smaller than larger. I can’t work effectively when fatigued, and fatigue can come on quickly with little notice. As such, my sessions in-studio are shorter. I spill something almost every time I work — water, paint, materials — so I’ve learned to work more carefully, consider where my body is and may be, as I get engrossed in creating. I produce less as I have less time to work on most days; I both have less energy and need more time for self-care.

As I paint, I have learned to be more thoughtful — as I have less time to work — and more thoughtless at the same time: just paint, don’t overthink, let what’s inside be expressed without excessive filtering. I appreciate the process of creating as much as, or more so, than the outcome.

Q. What did you learn about painting during the year?

A. Three large themes emerged in the work.

1. Complexity/simplicity. Much of the art has a focus on how much can be placed in the frame and having the painting feel coherent. Items are in a precarious balance. How simple can life be and still feel satisfying?

2. Memory. The beach paintings reflect a time when I grew up in Santa Monica, and loved going to the beach. It was a sensual place, and somewhere I felt at home and strong, swimming easily in and out of ocean currents. These were a reminder that strength is still a part of me, even when I feel overwhelmed and weakened.

3. Relationships. I painted both specifically and generally about how being with others feels, and how PD affects my relationships.

Q. And what about art in general, or even about life?

A. More generally, I’m learning that using a visual medium for expression can help clarify my feelings and words and make a changing internal world more understandable. Creativity and love are more important to my world now than logic and achievement.

The last painting I did was a canvas, “Semifinals,” based on the paper painting “Forty.” This painting captured much of how I now approach life. I see myself each day as having reached the semifinals. I’ve lived and played long. I’m tired. But I want to stay in the game even if that’s watching from the bench. And every day I come back to play in the semifinals. There is no prescribed outcome. I may struggle. I still play. I still return.

While I will always be an artist, career and achievement are now not so important. Living life well and being as loving as I can to others is what is important.

Q. What do you hope people will take away from seeing this body of work?

A. During this past year, I was constantly reminded that life goes on and that in many ways having PD is only one way, among many, that I can be physically and mentally challenged. During the year, I experienced hospitalization, deaths of family and friends, a studio change, a move. PD made these harder to get through, but not impossible. As I continue to learn more about myself and navigate new stages of illness, I want to be keenly aware that I need to show compassion every day, as best I can, toward myself, those I love, and those I don’t even know. Life is difficult, life is incredible. I want to live mine well. I want you to live yours well, too.

Q. You also published a book of the series?

A. I was wanting to have a record of the work that I could reflect back on over the years. The tangible nature of a book transmits more to me than a digital image. I realized that I had most of the elements already in place for a book as the work was scanned and photographed. I approached the book as a visual meditation, with text only in the foreword and afterword, so people can take their own visual journey without having to process the details of mine.

Q. What is next for you?

A. I have a show scheduled at Pirate for next April. No specific intention for it yet but I plan to keep working on paper, being open to exploring ideas and processes, and will see what happens.

IF YOU GO

“One to Somewhere” continues through Dec. 15 at Pirate Contemporary Art, 7130 W. 16th Ave., Lakewood. It’s free. Info: 303-909-5748 or pirateartonline.org. The artist will present a talk at the gallery at 2:30 p.m. on Dec. 14.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, In The Know, to get entertainment news sent straight to your inbox.

Originally Published: December 2, 2024 at 6:00 AM MST