NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / Andrew Levan

NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / Andrew LevanResearchers, including scientists at the University of Warwick, have been able to use the James Webb Space Telescope to analyse a kilonova for the first time.

Kilonovas aren’t quite as violent as supernovas, where a star goes boom, but it’s still an explosive cosmic event.

Astronomers also think they’re really important and would like to study them, but awkwardly they are rare and rapid.

So they don’t happen often and then are over before you can have a good look.

A kilonova is caused by two neutron stars spiralling towards each other then colliding. The resulting explosion first produces a blast of gamma rays lasting seconds.

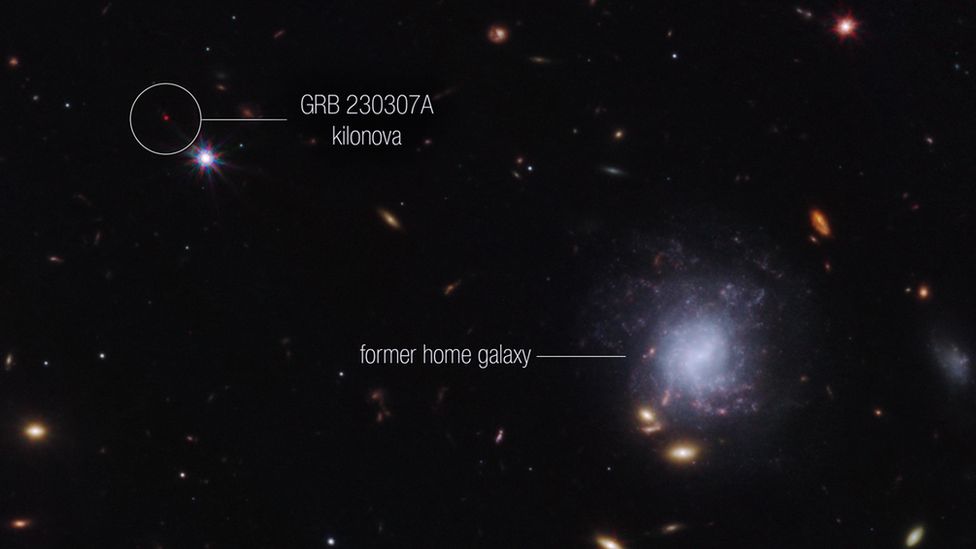

It alerted the astronomers to something big going on and they called it GRB (gamma-ray burst) 230307A.

In a race against time they moved quickly to ask other telescopes and detectors to look at the sky where the GRB had come from and what they saw revealed a kilonova exploding.

For the first time, they were able to analyse the heavy elements being produced by the explosion itself.

One of the nicest astronomy apercus is that we’re all made of “star stuff” – all the elements that make up everything in our lives were formed in stars.

First there’s the Big Bang and then the universe forms and it’s full of hydrogen and helium.

After that we need to wait for stars to appear and that provides a place for other heavier elements to be created.

Inside a star you get nucleosynthesis and that means helium turns into beryllium and carbon and eventually other elements, up to and including iron.

Then stars go supernova, which creates even heavier elements like nickel, and as a bonus the explosion spreads all these exciting new atoms across space.

But now we know we get other heavy elements in a kilonova, as for the first time astronomers managed to measure the signal produced by a heavy element called Tellurium.

This was predicted by models of what we thought happened inside a kilonova but now we have confirmation.

‘Exciting result’

Scientists have also managed to work out where the two neutron stars involved in the kilonova came from: a spiral galaxy 120,000 light years away from the location of the final explosion, measuring about the diameter of the Milky Way.

If their end took a matter of seconds in a kilonova, the two neutron stars took several hundred million years to get there.

It’s a very exciting result and there’s still a lot much more data for the astronomers to start combing through.

We may have even more to learn about the rare but fascinating kilonova.

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: [email protected]

Related Topics

- Astronomy

- Coventry

Related Internet Links

-

University of Warwick

-

Webb Space Telescope