Contributor Dereck Mangus guides us through the profound influence of technological advancements, drawing connecting threads from Degas to Duchamp and extending to the latest MoMA exhibition. This engaging article embarks on a captivating journey, illuminating the dynamic interplay between creativity and evolving technology.

Living in Boston during the early aughts, I attended an unusual art exhibition that now feels prescient. Installed throughout the gallery were these stations where people could arrange objects into different configurations on platforms in front of cameras. The items were random, colorful things like a yellow fuzzy ball or a red plastic pail. These still-lifes were then “interpreted” by a computer that spat out textual responses to the visual prompts. The computer-generated “poems” were mostly gibberish. Every now and then though, an uncanny lucidness developed in them, only to fall back into nonsense. I didn’t like the idea of machines making art then anymore than I do today. But as an artist and writer, I feel the need to address the subject now that it has become more pressing.

There’s been much discussion lately about the many ways artificial intelligence (AI) will radically alter our lives, our politics, and civilization as a whole. Much of the discourse is drowned out either by utopian prattle from cultish technologists or by dystopian dross from neo-Luddite naysayers. Don’t get me wrong: I aim to neither celebrate nor denounce AI. I have reservations about such brave new technologies. If you ask me, the jury’s still out on the Internet. Sure, it helped to make the world feel a little more like a global village for a few decades, but at what cost? Our democracy? From Obama to Trump, it’s easy to see how the positive (hope and change) and the negative (hate and fear) can become so closely juxtaposed with a jolt from the high-tech. How will more recent technologies like AI and Deepfakes further complicate our culture?

If it wasn’t for an earlier disruptive technology, modern painting may have never arrived at abstraction. A few decades after the advent of photography in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, a loose group of French painters began making pictures that went beyond photographic clarity. Impressionists sought to capture the activity of seeing itself, opting for a more gestural look over the crystal-clear focus of photography.

Following Impressionism, late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century European art became awash with painterly -isms: from pointillism and symbolism, expressionism and fauvism, to constructivism and cubism, futurism and surrealism, new painting styles kept popping up every few years. It was just a matter of time before the European avant-garde arrived at pure abstraction or non-representational pictures that do not depict things found in life. From interwar Europeans like Malevich and Mondrian to postwar Americans like Pollock and Rothko, abstraction became one of the most important developments in modern art.

Something similar will no doubt happen in the near future with AI: artists will try to figure out ways to create things that computer-generated images cannot, forging as yet unforeseen art forms. Others will work with the new technology. Impressionists like Degas used photographs as sketches for their paintings. Before the second half of the nineteenth century, painters almost always centered their subjects in the middle of their canvases, as with Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. Nobody ever thought to crop out a figure, like one of Degas’ bathers, until a snapshot of such a moment revealed how abrupt truncation can dramatically alter a composition. AI will surely lead contemporary artists to make similar discoveries.

Something about that exhibition in Boston reminded me of Dada and Surrealism, the interwar European avant-garde art movements that prized the irrational and the unconscious. The interplay between image, object, and text were of great interest to the Surrealists who invented the Exquisite Corpse, a parlor game where several participants collectively create a graphical or textual composition based on a few marks or words left by the previous person. Each player folds over most of what they add, leaving only a few hints–trace marks or dangling words–for the next person to build upon. Like the “poetry”-generating machines in the gallery back in Boston, the end results were more often than not absurd and meaningless. But every now and then one would border on something like a great work of art, or at least a really good sketch for one. Why couldn’t a computer take part in this activity?

AI-generated art has a harbinger with the Dadaists too, who, like the Surrealists, rejected aesthetics, logic, and reason. As is well known, Marcel Duchamp submitted a common urinal turned on its side as his entry for the 1917 exhibition by the Society of Independent Artists at the Grand Central Palace in New York City. Outside of an enigmatic signature scrawled along its side (“R. Mutt 1917”), there is no trace of the artist’s hand on this machine-made, mass-produced, quotidian apparatus. Fountain was ultimately denied a place in the show, the original lost forever (and perhaps not even by Duchamp.) A few later versions were authorized by the artist over the course of his career. Yet, through photographic documentation (the best of which was shot by Alfred Stieglitz soon after the Society of Independent Artists show) and textual documentation in the form of endless references in art history and art theory publications, Fountain has become firmly ensconced as one of the landmark works of twentieth-century art.

By placing a piece of plumbing on a pedestal, Duchamp figuratively knocked the artist off their own. If a found object—a porcelain urinal, in this case—may act as a prompt for philosophical discussions about art, was Duchamp not instigating a sort of low-tech, proto-AI-generated artform? Duchamp’s gesture helped turn the tide away from what he referred to as “ocularcentric” art, or art that stimulates the eye but not necessarily the mind, such as abstraction. This shift away from aesthetics and formalism towards the more theoretical would come into full bloom during the American postwar neo-avant-garde of the 1960s. What makes a work of art a work of art? Is it whatever the artist might select from a sea of images and objects? Does this not make the artist more of an editor or curator? If so, how different is the artist from the selector of prompts used in generative AI? Regardless of what the layperson may think about a urinal passing as a work of art, Duchamp radically altered the course of modern art history and helped to usher in what is now known as postmodernism. Rather than aesthetic appreciation, philosophical contemplation supports the Duchampian legacy, still very prevalent in contemporary art.

What are the ethical ramifications of generative AI? The winner of this year’s Sony World Photography Award turned down the prize in April after revealing his entry was generated by artificial intelligence and thus not a true photograph. German artist Boris Eldagsen intentionally deceived the award organizers with Pseudoamnesia: The Electrician, an eerie black and white picture depicting two women huddled together, “captured” in a grainy, classic sepia. On his website, Eldagsen describes his Duchampian ruse as a “historic moment,” adding: “I applied as a cheeky monkey, to find out if the competitions are prepared for AI images to enter. They are not.”

What if AI displaces human workers in the creative sector? From last May until early October, the Writer’s Guild of America (WGA) was on strike against the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. It was the longest interruption to American film and television production since the global closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Representing 11,500 screenwriters, WGA fought for, among more traditional disputes concerning pay models and benefits, protections against writers’ jobs being lost to AI.

As technologies created to create without creators continue to advance, this issue will become more complicated. Nonetheless, there will likely remain the need for at least some humans to make the initial prompts that AI responds to and later edit certain passages that don’t quite read correctly. Machines are still imperfect. I am not only pro-human, I am pro-union, and my heart went out to the workers during the strike. Yet, I can’t help but think that much of the formulaic drivel that finds its way into scripts for movies and TV shows feels as though it was churned out by a machine anyway.

The fact is, computer-generated art isn’t new and isn’t going anywhere. Algorithmic art, fractal art, and glitch art all employ the computer to create unpredictable visual outcomes and have been around for some time. When taking photos on your smartphone you have likely used the technology without even knowing it, as AI is increasingly baked into digital photography, helping to reduce visual noise and sharpen blurry photos. Most camera phone users care less about the art of photography than about taking selfies or “pics” of friends and family doing funny things to upload to social media.

In his essay on the subject, “On AI and the Intrinsic Value of Writing,” Maryland Institute College of Art professor of creative writing and literature Paul Jaskunas asks, “If a computer endowed with ‘artificial intelligence’ can produce a more grammatically sound, deeply researched, and convincing essay than you can, and is able to do so faster than you ever possibly could, why not rely on the machine to do your writing for you?” By shifting the pedagogy to emphasize the process of writing over its end product, Jaskunas posits that AI may actually aid his profession as composition teachers will be able to impart how the act of writing itself is meaningful and rewarding. Like photography in the visual arts, disruptive technology may help us to paint and see, write, and read in new ways.

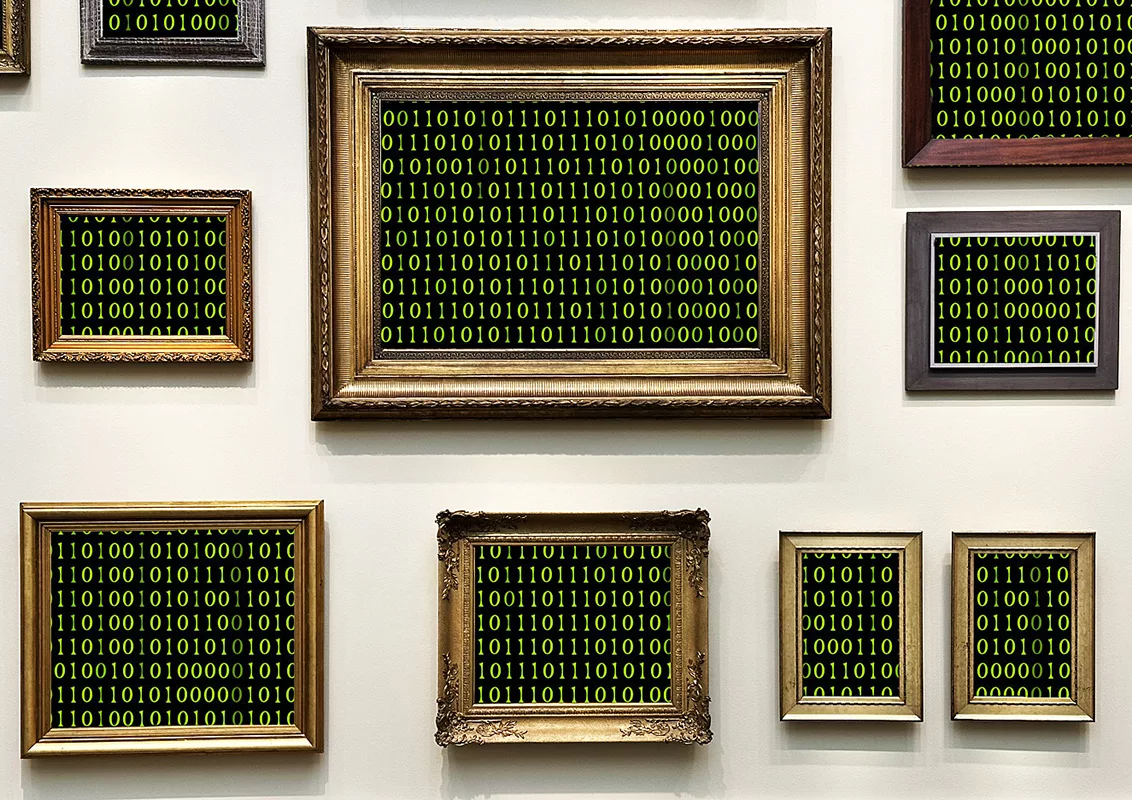

Digital illustration by Dereck Stafford Mangus

Work by the Turkish-American new media artist Refik Anadol (b. 1985) offers a sneak peek into the wild new forms generative AI may take in the future. His show Unsupervised, on view at MoMA through October 29th, asks the question: “What would a machine dream about after seeing the collection of The Museum of Modern Art?” By programming a computer to interpret the publicly accessible database of the museum’s holdings, Anadol creates mesmerizing moving pictures that undulate into nearly recognizable images only to fall back into abstract compositions, which then quickly morph into… Well, something else. By using other artist’s work as prompts to inform the creation of his own animated abstractions, Anadol synthesizes the two main threads of twentieth-century art: the pre-existing art from the database acts like found objects or Duchampian “Readymades,” providing a conceptual framework, while the final “movies” satisfy our aesthetic needs with lava-lamp-like enchantment. “I am trying to find ways to connect memories with the future,” the artist said, “and to make the invisible visible.” With exhibitions like Unsupervised, we catch a small glimpse of the future, a future that may appear wild, but not totally untamable.

Editor’s Note: Artblog articles covering A.I.:

Clayton Campbell – A Short Walk Through the Uncanny Valley of A.I. Art

Ruth Wolf – Artificial Intelligence and ‘Your Brain on Art,’ thoughts on two provocative topics

Lane Timothy Spiedel – The Imitation Game – An Artist’s Role in Latent Space

Beth Heinly – The 3:00 Book

Oli Knowles – Socialist Grocery

Article Update: Refik Anado’s Unsupervised – Machine Hallucinations has been purchased by MoMA