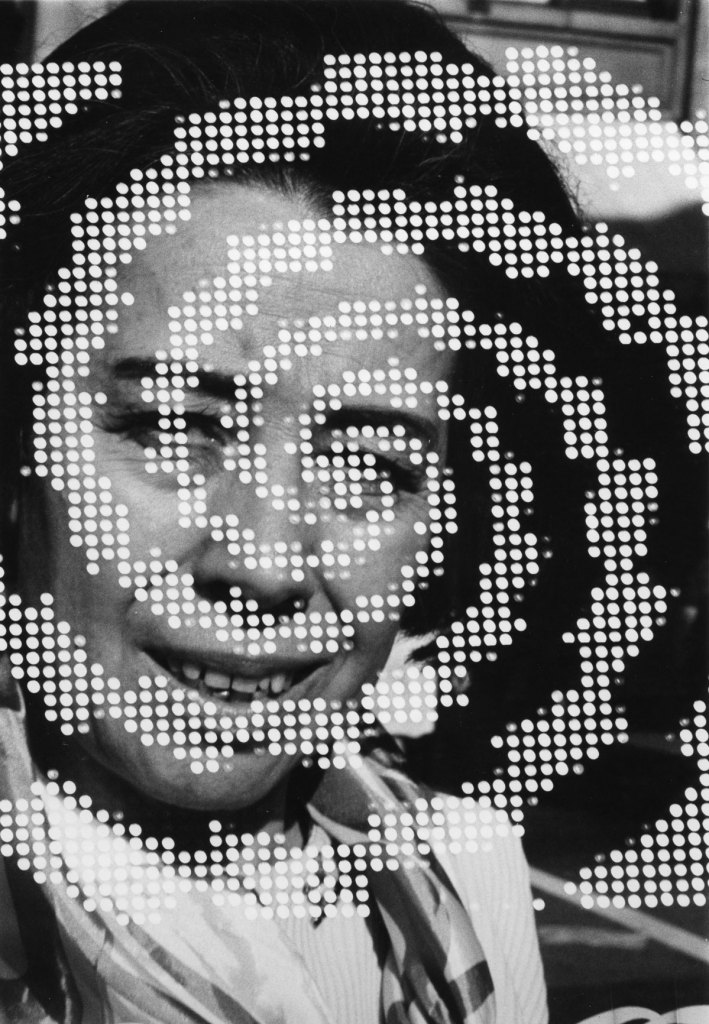

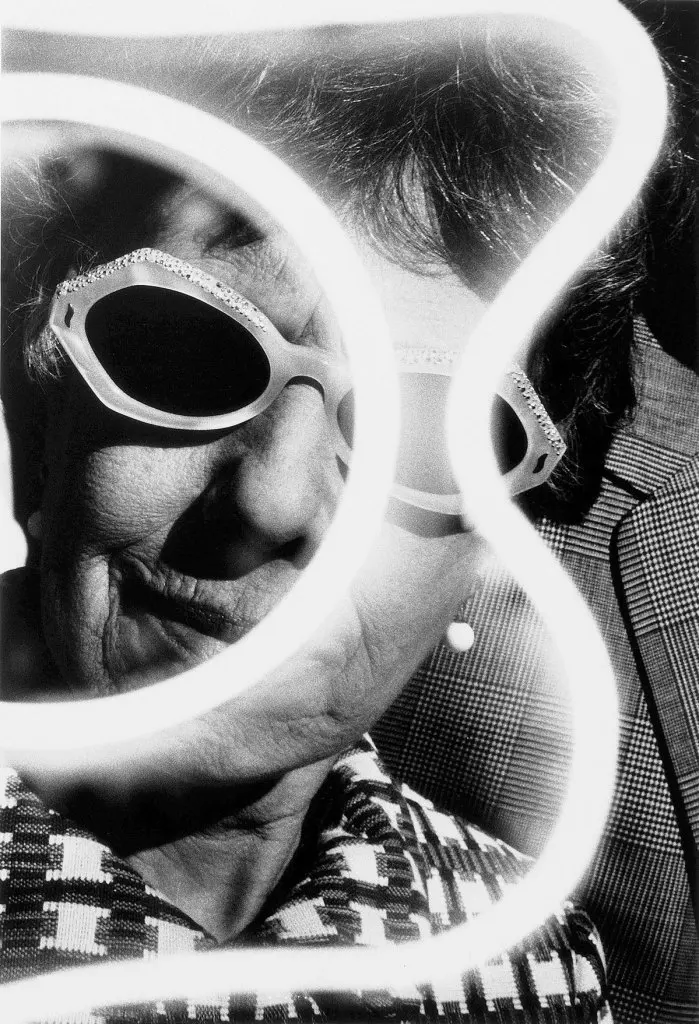

Barbara Crane (1928–2019), the legendary Chicago artist behind this week’s cover, said, “Once I developed my first roll of film in 1948, nothing else mattered.” What followed was decades of daring formal experimentation, defined by a connection to Chicago’s social and physical landscape. Her current solo exhibition at Paris’s Centre Pompidou features over 200 works from the first 25 years of her practice. It’s accompanied by a new monograph published by Atelier EXB. Below, Lynne Brown, an artist and former studio manager to Crane who helped develop the show, talks about Crane’s history and legacy.

James Hosking: When did you start working with Barbara?

Lynne Brown: I first met Barbara in the early 1980s when I was a graduate student at SAIC, and we became friends. It must have been 2007 when she asked me to stop by her studio to look at the book she was working on that accompanied her retrospective exhibition, 2009’s “Challenging Vision,” that was being organized by the Chicago Cultural Center. Barbara wanted me to help her with the sequencing and organization. I spent the afternoon and came back and spent the next day, and the next, and the next, and never left.

How do you think that Barbara’s early time at the Institute of Design, with its grounding in the Bauhaus and the work of László Moholy-Nagy, influenced her work?

It was transformative. She had been working as a photographer for many years: making portraits of neighbors’ families or businessmen’s portraits, but that held no interest for her anymore. She was familiar with Aaron Siskind’s work, who was running the program at the Institute of Design, and she arranged to show him her work. He said, “I don’t take private students, but why don’t you come into the master’s program?” She said, “Oh, no, I can’t do that.” She woke up the next morning and called him and said, “How do I apply?”

Courtesy of the Barbara Crane Studio Archive, © Barbara B. Crane Trust

As I became more familiar with Barbara’s work I was struck by the distinct series she created. What is the methodology behind them?

It’s hard to say if a series evolved over work that coalesced into an idea or if she approached things as an idea and pursued that in-depth. I think both of those would happen over time. The idea might change and shift, but it was all within the context of a larger series or concept. Some series had a discrete period of time while others would happen over a longer period concurrent with other series.

She often would talk about having summer work and winter work. In the summers, it was important for her to get out and photograph and be around people. She felt isolated largely because her children would spend the weekends with their father. So she would photograph in crowds of people resulting in series such as Beaches and Parks (1972-1978) and Private Views (1980–1984). These are examples of summer work made out in the world. Winter work, series such as Still Lifes (1997–2002) and Objet Trouvé (1982–1988), were photographs of objects she collected and found fascinating that were made in the studio.

How did the show at the Centre Pompidou and the accompanying book come to be?

The curator, Julie Jones, did her PhD on U.S. photography in the 30s and 40s, with a focus on the New Bauhaus and the Chicago School, and that’s where she first discovered Barbara’s work. As a woman and a single parent with three children, Barbara’s work wasn’t always taken seriously by her professors and male peers. She was often up against preconceived ideas of what a woman’s role should be. Julie had an interest in making Barbara and her work more present.

How would you characterize Barbara as an artist?

A friend who also knows Barbara and her work very well characterized her as experimental, expansive, fearless, inspired. She couldn’t not make work. She had to do it. She would challenge herself all the time. With the series People of the North Portal (1970–1971), she would position herself with a large-format 5×7 view camera outside one of the entrances of the Museum of Science and Industry and photograph people coming out the revolving doors. Some of the photos are closer up, some of them are farther back. She thought through what are the possibilities here? She always talked about how influential mistakes were. She would find a mistake compelling and would pick it apart and pursue it. Barbara approached the world with a childlike wonder and heightened fascination that she brought to her photography.

What was her relationship to Chicago?

Barbara was a lifelong Chicagoan, and she saw herself that way. She was very connected to the city and felt that she did some of her best work here, because she could always go back again and again and again to what she was photographing. She didn’t like taking travel pictures. It didn’t interest her.

How did Barbara want to be remembered?

Her legacy was definitely important to her. She wanted her work placed well so that it would live on beyond her lifetime. Barbara always would say, “If I die”; she would never say, “When I die.” She loved living, and she hung on to it as long as she could. There was something about connecting with the world through her work and the process of discovery that was so important to her.