Abstract

Indigenous and traditional knowledge of the natural environment is crucial for policymakers and community leaders in Vanuatu. Here, we employ a mixed-methods approach to collect data from East, North, and West Area councils in Ambae Island, Vanuatu, and investigate the integration of science and local indicators to predict the presence of ciguatera fish poisoning to enhance community responses to health risk management. We found fourteen local indicators for the ciguatera outbreak. We also identified uses of scientific information from various sources to verify their Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge before making decisions. This led to the development of ‘The Gigila Framework’ to integrate Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge with science. We also found that both community and government agencies recognize the importance of incorporating community roles into the overall early warning system for ciguatera fish poisoning in Vanuatu. Our study highlights the need for government agencies to collaborate with local communities to evaluate and develop the best practices that enable the integration of Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge with science to improve community responses to health risk management in Vanuatu.

Similar content being viewed by others

Involving citizens in monitoring the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

Accounting for existing tenure and rights over marine and freshwater systems

Intentional Ecology: Integrating environmental expertise through a focus on values, care and advocacy

Introduction

As Ciguatera Fish Poisoning (CFP) becomes increasingly prevalent in tropical regions, including Vanuatu, the government and health authorities must urgently address this issue, especially the early predictions of CFP. CFP has become a public health risk in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world1 and is a seafood-borne illness caused by consuming fish that have accumulated ciguatoxins. The highest incidence rates of CFP are consistently reported from the Pacific and Caribbean regions2. Research has been conducted to determine the toxins that cause CFP3,4,5,6. Similar work on using Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge (ITK) in fisheries management has been performed to prevent, manage, and treat fish poisoning6,7 and to provide tools for adapting to climate and environmental change8. However, there is still a need to understand the ecological factors that cause the presence of ciguatera. This approach will bridge the gap of early information between ITK and science to inform the general public about potential outbreaks before ciguatera is discovered in fish or other marine invertebrates.

In this paper, we embark on a collaborative journey with the indigenous people of Ambae Island in Vanuatu, respecting and valuing their ITK and exploring how they deploy it to monitor and respond to environmental conditions and changes at the local level, which includes identifying and mitigating the environmental health risks associated with CFP. While there is a wealth of research into how Indigenous communities around the world use the ITK to sustainably manage natural resources, reduce disaster risks, and adapt to the impacts of climate change9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, far fewer studies have specifically examined whether and how individuals and communities utilize the ITK and its integration with science to maintain their health and wellbeing.

The ITK context is designed to fit with a social-ecological framework19. Indigenous communities such as Ambae Island, where government services are limited, rely on the natural environment for food, manage land use, and gather information on potential public health risks. Understanding ITK is crucial in informing Indigenous communities about managing potential health risks such as CFP. These communities have a strong connection with nature and possess first-hand observations that can provide early warning information about their livelihood and health risks.

In this paper, we focus on ITK as a localized system encompassing knowledge, practices, and values that influence various aspects of individual and communal lifestyles, which includes livelihood strategies, perceptions and responses to environmental risks, environmental governance, and management systems, all of which hold significance in addressing the socio-economic challenges confronting humanity. ITK is deeply rooted in lived experiences and practical interventions20. It pertains to local ecosystems, governance, management, overarching ways of life, worldviews, and ethical frameworks21. Within the context of this study, the term ITK refers to the indigenous knowledge utilized by the residents of Ambae to monitor changes in environmental conditions that may impact their well-being and overall health.

The ITK has been widely acknowledged for its ability to practically monitor environmental changes in hydrometeorological events such as floods and landslides9,10,11,12,13. For example, the Indigenous people of Vanuatu used the ITK to predict the onset of strong winds from the severe Tropical Cyclone Pam in March 201514 and from geological hazards such as tsunamis15,16,17. Local knowledge from elderly people on Simeulue Island in Indonesia helped them survived the destructive Indonesia tsunami in 2004, resulting in only seven out of the seventy-eight people dying17. The ITK has contributed to informing health risk policies by integrating malaria control programs in Africa21,22,23. Developing this integrated health alert system could help people recognize indigenous people’s ITK and promote its integration for planning and policy implications.

Scholars have identified numerous challenges in integrating scientific knowledge and ITK24. These challenges include organizing, identifying, and selecting knowledge from various sources and assessing its relevance, reliability, functionality, effectiveness, and transferability. There is also a risk of losing the moral and ownership aspect of ITK due to a need for recording and archiving for easy future access and use25. Additionally, challenges include the ambiguous meaning of languages used in the integration process and the need to demonstrate successful implementation of the integration26. Furthermore, it is necessary to address the biased worldviews of Western scientists towards ITK systems27. Lastly, ITK must be scientifically tested before being accepted as knowledge28. These challenges need to be addressed before attempting to integrate ITK and science.

Despite these challenges, using multiple knowledge systems can provide essential benefits and offer improved information and approaches to reduce communities’ vulnerabilities to environmental hazards29. Furthermore, some identified elements contribute to integration success and foster trust in relationships. In particular, the personalities of researchers are crucial; choosing the right local partners is essential, and there is a need for additional collaboration between researchers and local communities26. Bringing this research back to the communities and helping them to contribute their expert local knowledge is important for building systems that benefit both the local population and science communities30.

To incorporate ITK and scientific approaches in health risk management, a participatory downscaling approach is an option in which scientific information is translated into ranges of outcomes at the local level with the support of ITK31,32. This research aimed to investigate whether and how the ITK was used by indigenous Vanuatu people (Ni-Vanuatu) to predict and respond to ciguatera outbreaks and how it could be integrated with science for public health risk management in Vanuatu. Three areas were identified: ITK indicators for Ciguatera, a platform for integrating ITK with science, and perspectives from community and government agencies on the integrated early warning platform. There is a need for national and provincial governments to work with communities to identify best practices for the ITK to be incorporated with the sciences to improve community health risk management, particularly for CFP outbreaks.

Results

Community and Governmental perspectives

The people of Ambae have acquired vast understanding of their ecosystems through extensive personal observations and interactions, enabling them to adapt to environmental changes that shape their beliefs and practices. People often attribute issues to the strange behavior of plants or animals, a belief deeply ingrained in their beliefs and experiences. The knowledge of ciguatera, a type of fish poisoning, and its environmental impact has been transmitted through generations. Most interviewees, who have firsthand experience of CFP after consuming reef or offshore fish, share their personal stories with a sense of empathy and understanding.

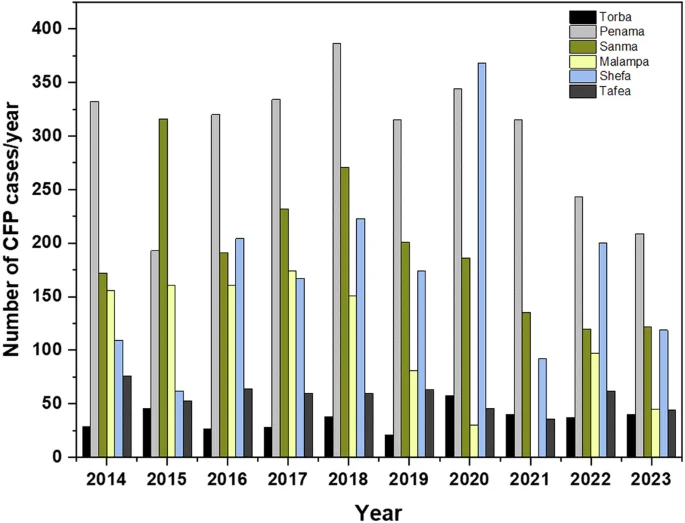

The study participants observed changes in the marine environment associated with increased ciguatera contamination cases. Penama Province, which includes Ambae Island, has had many CFP cases since 2014 (Fig. 1). The years 2016 to 2019 and 2021 to 2023 have seen the highest number of recorded instances compared to other provinces. According to the traditional knowledge of community elders, certain fish have always been known to be poisonous and can be easily identified. However, residents have recently noticed that many previously considered non-toxic fish are now believed to be poisonous or toxic due to ciguatera. This emerging trend is a cause for concern. Interviewee A5 pointed out that there has been enormous change – fish that had not been poisoned before are now contaminated or poisoned. Similarly, Interviewee A12 stressed that environmental changes, especially on the reef, resulted in new reefs and a new variety of algae growing, which had not been seen there before. When the fish feed on these algae and get contaminated with ciguatoxin, people who eat the fish get sick with CFP.

This graph shows the total number of ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP) cases for each province in Vanuatu from 2014 to 2023. Penama Province (gray bar) recorded the highest number of cases for every year except 2020, Shefa Province (sky blue bar) recorded highest in that year. Torba Province (dark gray bar) recorded the lowest cases.

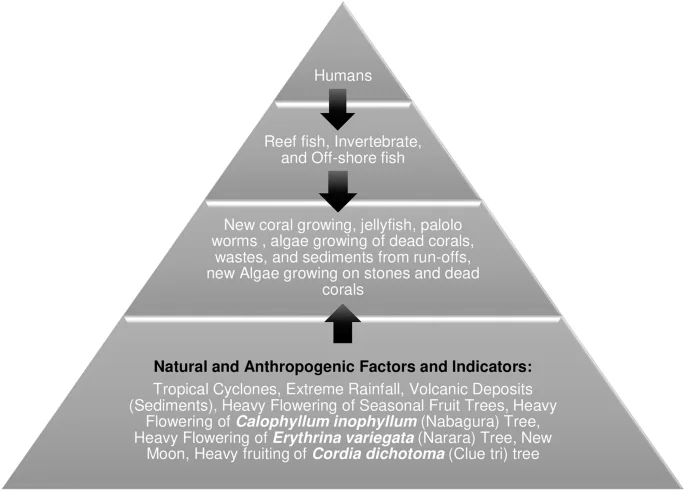

The communities believe that toxins in fish can be attributed to various environmental factors, such as volcanic sediments, surface runoff from land, dead jellyfish, and when fish feed on new coral reefs. This progression of ciguatoxins moves up the food chain (Fig. 2), eventually reaching humans who consume the fish.

The understanding of the communities that natural and anthropogenic factors and indicators contributed (upward arrow) to produce favorable environmental conditions for the marine plants and animals to grow and produce ciguatoxins that contribute to ciguatera. The fish and other invertebrates feed (downward arrow) on these plants and animals and humans feed (downward arrow) on fish.

The residents of the North Area Council of Ambae understand that the cause of fish poisoning in the area is more closely related to the heavy rainfall between 2020 and 2023 and the sediments deposited during the volcanic eruptions of 2017 and 2018. Interviewee A17 explained the factors that impact the food chain ultimately affect the people who consume the fish. After their return from the island of Maewo in 2019 and 2020, they noticed many changes to the marine environment, especially the new coral growing with a lot of new algae growing on dead corals, which they had never seen before. During the eruption of the volcanoes in 2017 and 2018, volcanic ash deposits killed these corals. During 2021 and 2022, they experienced so much rain, resulting in many volcanic sediments being washed down to the ocean through creek channels. The island has many creeks, most located in the northern and western parts. These creeks are crucial for carrying volcanic deposits that have been washed down to the coast and flowed into the ocean during heavy rainfall. Because of their location, the creeks serve as natural channels, making it easy for volcanic deposits to reach the sea. These creeks are essential to the island’s ecosystem as they provide habitats for various aquatic species, and their banks are a source of nutrients for the surrounding vegetation.

A large proportion of Vanuatu’s population, approximately 80%, reside in remote and rural villages33, which poses a challenge in accessing pertinent government services and information. This prediction becomes more cumbersome when there are rapid changes in the environment due to climate change or other natural hazards, such as volcanic eruptions. We interviewed thirty-seven individuals to evaluate the importance of the ITK and its role in local ecological monitoring of environmental changes. The study’s respondents strongly emphasized the criticality of the ITK, given its accessibility and ease of application or use. It is a consistent tool rooted locally and traditionally in living on islands. It is the first source for obtaining information about environmental changes that could impact people’s health and well-being. Local people rely on indigenous and traditional ecological knowledge to monitor environmental changes before making decisions. Interviewee A34 explained that Local knowledge is locally available, helps manage resources from the land and marine ecosystem, and comes naturally from God to be used and applied by local people. Interviewee A15 stated that local indicators are like first-hand information since they are locally available, free, and available.

The findings from fieldwork data analysis indicate that 92% of the participants considered ITK an indispensable source of information about environmental change. Other sources, including community discussions, radio, social media, and local university student reports, are also perceived as beneficial for accessing information on potential environmental risks. Notably, Interviewee A20 underscored the critical role of the ITK in monitoring the environment for probable ecological hazards. While living on the islands for many years, their relationships and interactions with nature allow them to tell when such events will happen. They thank God daily for providing them with everything. Whenever they came across a sign that nature showed, they knew it was from God, and they must inform their families to prepare. This knowledge is free from God for them to use to sustain their living and to be resilient to what nature will impose on them. They claimed that nature provides challenges when it sees fit and also informs them to prepare to face them. Most of the community members know or have some knowledge of ITK, how to do certain things, and how to maintain ancestral beliefs and practices

Indigenous and traditional knowledge indicators for ciguatera fish poisoning

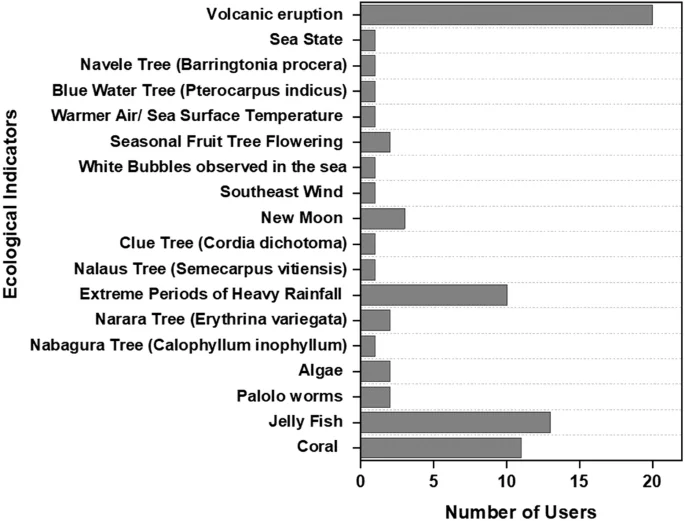

We investigated whether local communities have a local alert system to inform them of a potential ciguatera outbreak. Our study showed that local populations utilize ecological indicators or signs such as fauna, flora, atmosphere, and geological and astronomical events to indicate potential environmental risks that could negatively impact their health and well-being. We identified fourteen local indicators during the interviews with the communities. These indicators respond to changes within the natural environment that provide alerts to local communities on potential health risks, such as CFPs (supplementary Table 1). These indicators are analysed against their local user as shown in Fig. 3. Four indicators or ecological signs are the predominant indicators used by communities to monitor environmental changes related to the ciguatera outbreak; these indicators include extreme periods of heavy rainfall resulting in substantial surface runoff, a dense aggregation of jellyfish around the reef and near-shore areas, the proliferation of new corals within the reef area and ashes deposited by volcanic eruptions.

Four indicators are the predominant indicators used by communities to monitor environmental changes related to the Ciguatera are extreme periods of heavy rainfall, a dense aggregation of jellyfish around the reef and near-shore areas, the proliferation of new corals within the reef area, and Volcanic ashes.

During the interviews, the participants described how each ecological indicator is connected to ciguatera in fish, which resulted in fish becoming contaminated with ciguatoxins. These indicators are linked to changes in air and water temperature, water from certain types of trees, specific algal species within reef areas, or the behavior of certain fish. For instance, Interviewee A12 elaborated on the connection between ciguatera and these ecological indicators, shedding light on how each one might influence the occurrence of the disease. During heavy rainfall, water from the Semecarpus vitiensis (Naulas tree) is washed down the streams, poisoning eels. When poisoned water reaches a reef, the reef fish are contaminated. Rainfall also washes waste and sediments down to the sea, contributing to favorable environmental conditions for algae growth. The fish will feed on the algae, and we eat the fish and get sick. Cordia dichotoma (clue tree) fruiting occurs with warmer air temperatures. The heavy appearance of jellyfish and new coral growing on the reef may signal a potential risk of toxic fish during the upcoming months.

The Ambae people demonstrated an understanding of the island’s phenology, which involved the study of the timing of recurring biological events and their relationships with seasonal and climatic changes. The interrelationships between living organisms and their environment’s nonliving factors are known. They observe how flora and fauna on the island respond to natural changes such as temperature, rainfall, and sunlight and how these changes affect the growth, reproduction, and survival of these organisms. This knowledge is transmitted across generations and forms a crucial component of the daily lives of the people of Ambae Island. They also use this knowledge to make informed decisions regarding agriculture, fishing, and other activities that rely on the natural environment.

Validation and dual usage or integration

We have examined various policies and plans from Vanuatu and other regional and international organizations to find ways to integrate ITK with scientific knowledge for potential early warning systems for CFP. Nevertheless, no clear solutions exist for developing a framework combining the two pieces of knowledge, although some mention using ITK with science. However, the ITK information and understanding of environmental management challenges are mentioned in a few policies and plans34 (supplementary Table 2). There is a need for collaboration between scientists and local knowledge experts to develop an early warning framework suitable for both scientific and local communities30. For Vanuatu, this study stresses that national and provincial governments must recognize the value of traditional knowledge and work with Indigenous communities to assess and identify best practices that can be integrated with scientific knowledge to address CFP outbreaks. The generation of knowledge must facilitate a decision-making process that addresses the needs of both indigenous and scientific communities30.

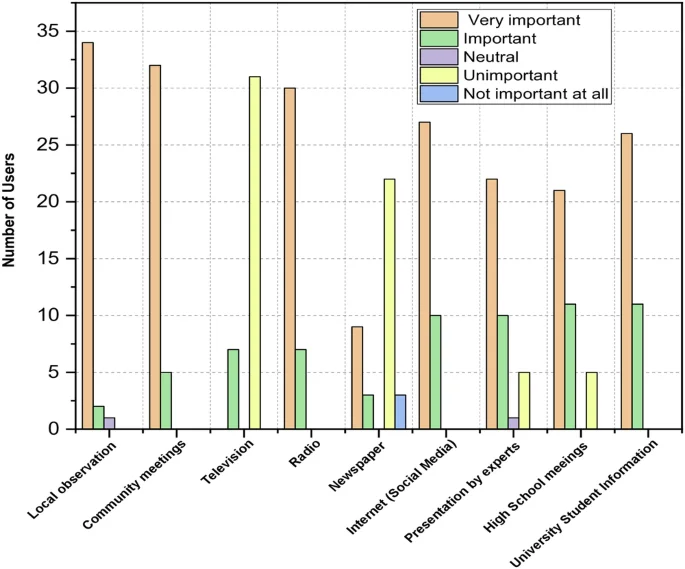

With technological advancements, the people of Ambae have access to scientific information on potential environmental risks to verify their ITK before making decisions. Figure 4 illustrates different sources on community livelihood decisions. The potential for integrating ITK indicators of CFP outbreaks with climate and fisheries early warning information from the Vanuatu Meteorology and Geo-Hazards Department (VMGD) and the Vanuatu Fisheries Department (VFD) allowed for the development of an integrated platform that is accessible, knowledgeable, acceptable, understandable, and valuable to both scientific and indigenous communities. This approach will strengthen the Vanuatu Department of Public Health’s (VDPH) ability to proactively provide health advice to the general public on potential CFP outbreaks. Integrating ITK with science can provide more and better data to enhance local response and adaptation efforts during rapid environmental changes such as CFP outbreaks.

Different sources of information are used by the communities to make informed decisions about their livelihood.

VMGD issues information on atmospheric phenomena such as extreme rainfall and tropical cyclone predictions, El Niño-Southern Oscillation events, and ocean phenomena such as sea surface temperature, sea level forecasts, and coral bleaching outlooks. The VFD recommends actions for people throughout Vanuatu to avoid lagoon and reef fishing if the coral bleaching alert is at its highest level, the chlorophyll concentration near the shore is above average, and algal blooms are observed in the area, especially in lagoons35. The ecological factors that trigger coral bleaching and high chlorophyll concentrations include nutrients and sediments carried by surface runoff during extreme rainfall36, similar to what was observed by people of Ambae after extreme rainfall events.

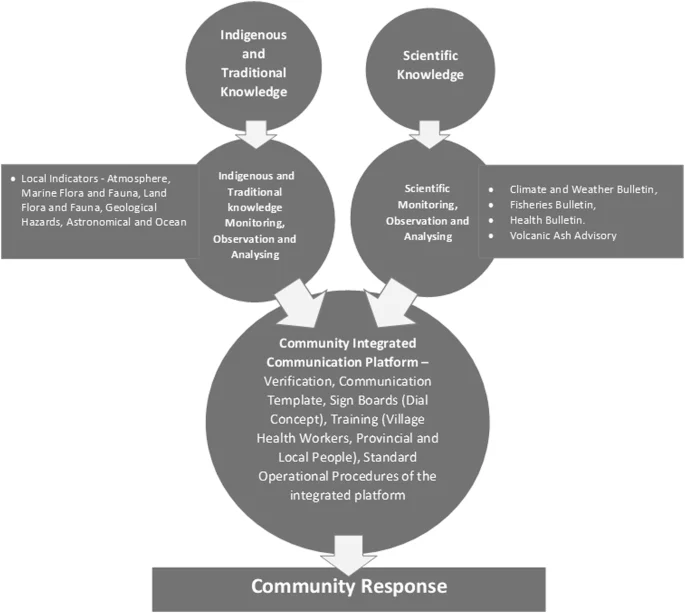

ITK indicators mentioned atmospheric phenomena (periods of extreme rainfall, hot and warm weather, southeast winds), astronomical phenomena (new moon), flora (heavy flowering of seasonal fruit, heavy flowering of Calophyllum inophyllum (Nabagura tree), heavy fruiting of Cordia dichotoma (Clue tree), water from Semecarpus vitiensis (Walahi tree), heavy flowering of Erythrina variegata (Narara tree) and heavy presence of algae), and fauna (heavy presence of jellyfish, palolo worms and high number of new corals growing on the reefs and ocean phenomena (while bubbles are observed in the sea). While the Fisheries Climate Bulletin is regarded as a national advisory issued by two government agencies, the VMGD, and the VFD, this information needs to be downscaled to fit the different local communities around Vanuatu depending on the island’s geography. Table 1 summarizes ITK and science indicators, ITK indicators behavior, the outcome of science analysis, and the impacts related to ciguatera. The ITK indicators provided by local people can bridge this information gap. We designed an integrated downscaling model, termed “The Gigila Framework” (Fig. 5), for the CFP outbreak in Vanuatu based on the data from the people of Ambae and the data and information from the government agencies.

This framework of knowledge co-existences where Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge, and science systems are acknowledged and drawn to co-produce relevant forms of knowledge and practical applications.

The study delves into the current status and significance of ITK on Ambae Island. It identifies opportunities to merge ITK and scientific knowledge to forge methods for monitoring environmental risks and crafting risk reduction strategies for the people of Vanuatu. This is a beacon of hope, especially in the wake of the recent IPCC report, which warns of the adverse effects of climate change on global communities37, with a particular focus on small island developing states like Vanuatu This project is a testament to the potential of a bottom-up approach, empowering Indigenous communities to build resilience and mitigate health risks associated with disasters and public health emergencies38, such as the outbreak of CFP.

There is the potential that changing environmental conditions may reduce the reliability of current ITK indicators, which may present challenges for Indigenous communities in the future, the depth and dynamics of ITK (which includes information dating back for thousands and sometimes tens of thousands of years) means there is the potential for ITK indicators to be more adaptable39. Moreover, leveraging ITK and scientific knowledge to assess health risks can provide valuable benefits for the communities of Ambae Island, which means that the weaknesses of the different knowledge systems are mitigated.

Verifying ITK and scientific information is crucial for helping Indigenous communities make well-informed decisions aligned with their livelihoods and well-being. Unlike scientific knowledge, ITK must be verified for its reliability and effectiveness in public information and other forms of knowledge40. The verification process involves establishing a network of local observers to collect ITK data from ecological indicators over extended periods (years) and cross-referencing this information with scientific data based on historical climate and geological events. Stories and records of past events shared by ITK experts, which serve as practical applications of ITK, have been used as indicators to predict hazards and compare them with scientific records from government agencies. These practical applications of ITK, such as predicting hazards, demonstrate its relevance and usefulness in real-life situations. When integrated with scientific data, these ITK indicators lead to more comprehensive and accurate information for decision-making. These ITK indicators are commonly used and considered the best predictors of CFP. ITK indicators support the precise interpretation of environmental changes and enhance the robustness of adaptation strategies at the local scale41. These ITK data will be documented and archived alongside scientific information for future reference. By integrating both sets of knowledge, the Indigenous community in Ambae can validate ITK indicator information with scientific data, empowering them to effectively utilize and manage information, ultimately leading to improved decision-making in mitigating health-related risks.

The Gigila framework: integrated early warning platform for ciguatera fish poisoning

We incorporated the “Gigila Framework” to develop an integrated early warning system. The term “Gigila” refers to the onset of risk used by the people of Ambae and Pentecost Island in the Penama province, indicating a high probability of risk occurrence. This framework perfectly fits our recommendation, which combines local indicators and modern analysis (information bulletins) to create a downscale platform that is accessible and easily understandable for local communities. We are not attempting simplistic knowledge but rather knowledge co-existences where ITK and science systems are acknowledged and drawn to co-produce relevant forms of knowledge and practical applications.

Our study has practical implications for the field, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrating ITK and Western knowledge to strengthen environmental risk assessment. Similar approaches of using ITK and Western knowledge in enhancing environmental risk assessment by integrating knowledge systems have been documented30,32,39. For this study, we used ITK indicators and scientific information from government agencies to create a combined platform for CFP. This early warning platform, depicted in Fig. 5, comprised four key elements: knowledge, monitoring and analysis, warning communication platform, and community responses42. By incorporating ITK into this concept, we aim to enhance local people’s trust and recognition of their roles in the overall early warning system for CFP in Vanuatu. The communities need access to updated risk knowledge from more comprehensive public sources and platforms that are easier to understand and have fewer technical and educational barriers43.

An integrated communication platform has been developed to disseminate information regarding the risks associated with the CFP outbreak. Drawing upon ITK and scientific analysis, the platform employs a dial concept to categorize risk levels from low to high. Crucially, it is imperative to provide training to the provincial government, local community observers, village health workers, tourism operators, and local fishers within the communities. This training endeavor aims to give these stakeholders the necessary knowledge and skills to utilize the communication platform effectively. Furthermore, implementing this model will be guided by a standard operational procedure.

The training aims to simplify scientific terms for local communities, enabling them to make informed decisions about their health and well-being. This initiative is particularly relevant due to the increasing use of technology, which underscores the need for local people to be more discerning about scientific information from social media. Therefore, this platform aims to simplify scientific information and prevent misunderstandings. An integrated communication platform is essential for local communities and the general public to understand the risks of CFP. By providing the necessary training, we ensure that the platform is effectively utilized and that scientific information is simplified for easy understanding by local communities.

The platform is administered by local community members who own it entirely. The community elders appoint local observers with a proficient background in utilizing ITK indicators for decision-making. These local observers serve as primary contact points and relay environmental changes to the early warning platform based on local indicators. Village health workers will be the primary contact for information provided by government technical agencies such as the VMGD, AFD, and the VDPH. Following a data verification process from ITK and scientific agencies, the village health workers and local observers are tasked with disseminating final information to the community. This information is conveyed to the community members using a dial concept or direct communication to ensure widespread awareness.

Discussion

This research project highlights the value of the ITK in informing communities about potential environmental risks and how it integrates with science to improve community responses and adaptation to health risks, notably the CFP outbreak on Ambae Island in Vanuatu. Our study will improve CFP prediction and management at the national, provincial, and local community levels. Broadly, the health sector will use this study to inform its communication strategies in the remote places in Vanuatu where health workers are present to allow for better coordination among communities and the government. The involvement of local communities and health workers in the overall early information platform will preach the message of early warning to the people in the area31.

This study provides a framework for developing a participatory warning system in which local people in communities contribute their expert knowledge to engage fully as citizens in response to the impact of environmental health risks. Moreover, how can their local knowledge be used in parallel or integrated with scientific knowledge to create a platform that is accessible, understandable, and responsive to both local and scientific communities? A similar concept has been developed for malaria and other vector-borne diseases21,43,44, emphasizing the importance of ITK practices and worldviews for supporting policy development and decision-making processes across all sections of society, from the national to the local community level. This study investigates the factors that may trigger the presence of ciguatoxins, which can result in fish poisoning and may apply to other parts of Vanuatu or other Pacific Island countries.

Many studies support the importance of the ITK in environmental monitoring but emphasize that it should be integrated with science45,46,47,48,49 to improve community response and adaptation to environmental changes. Our case study highlights the significance of the ITK for the lives of the Ambae people in Vanuatu. We support the Gigila concept for ITK and science. However, we argue that the ITK can also operate independently or in parallel with science to inform communities about environmental risks14. This study revealed that 92% of local inhabitants rely on the ITK to monitor ecological changes. While ITK is crucial for monitoring environmental changes, other sources of information, such as social media, radio, expert presentations, and educational awareness, are equally vital. For instance, most people in Vanuatu use Facebook, a popular social media platform, to share information on natural and anthropogenic issues that may threaten community livelihoods. In light of this, the sustainability of the ITK and the interest of locals in learning more about it should be carefully considered, given the already felt presence of scientific understanding at the local level.

We evaluated the feasibility of establishing a local alert system based on ITK indicators, primarily focusing on the risk of CFP outbreaks on Ambae Island, including other parts of Vanuatu. Community early warning systems have been documented in the literature; these systems concentrate on natural disasters such as tropical cyclones, floods, landslides, and tsunamis50,51,52,53,54,55. Some studies have focused on using local and traditional ecological knowledge to prevent, manage, and treat fish poisoning7,56,57,58 and regional environmental knowledge of hotspots and cold spots in Ciguatera6. Researchers have also explored the integration of Ciguatera risk into systematic conservation planning59. Scant literature has addressed the ecological risks related to Ciguatera outbreaks. Our case study showed that the ITK was useful for understanding the environmental factors that trigger the presence of Ciguatera in the three area councils of Ambae, and this could be integrated with science to improve ciguatera prediction.

Our case study revealed that the inhabitants of Ambae rely on ITK indicators to obtain information regarding environmental changes, particularly those that could trigger a Ciguatera outbreak. All of the people interviewed know one or more ITK indicators. The heavy presence of jellyfish, the emergence of new coral over large areas, and periods of heavy rainfall that caused heavy surface run-off are some indicators commonly used by people in CFP prediction in the three area councils. This indicates that the ITK is crucial for the people of Ambae to comprehend and react to environmental risks.

We discovered that the risk of a ciguatera outbreak can also be triggered by volcano ashes deposited directly into the ocean and by sediments being washed into the sea by surface runoff60. Ambae Island experienced two large volcanic eruptions in 2017 and 2018, forcing the entire island to evacuate to neighboring islands, Maewo, Pentecost, and Santo58. The volcanic ash and sediments from these eruptions continue to largely impact the island’s marine environment. The people of the North Area Council have noticed changes in their aquatic environment since they returned to the island in 2019 and 2020. Different algae that grew on dead coral were not observed before the eruption, and fish and other invertebrates that were not previously toxic are now contaminated with ciguatera. Volcanic ash deposited during volcanic eruptions alters marine ecosystems61 and may result in diverse bacterial communities62. Volcanic ash contains diverse chemical compounds that can contribute to nutrient enrichment5, leading to changes in benthic composition that might trigger Gambierdiscus spp., a ciguatera-related genus63. This might be the case with the North Area Council of Ambae Island people.

The interview results showed that the community’s understanding of the ecology of Ciguatera is based on their knowledge of the factors responsible for CFP outbreaks and exposure to humans. They understand the ecology of ciguatera based on what they observe and how they interact with the environment. These authors linked the outbreak to sediments (nutrients) being carried by surface runoff during periods of heavy rainfall, an abundance of jellyfish near the shore, the large number of new corals observed in the reef area, and other natural factors. Similar ecological factors that result in ciguatera infection have been observed for many years and can become triggering factors whenever they are noticed. The participants who had lived on the island for many years and had been infected with Ciguatera understood their symptoms, including flu, sore throat, diarrhea, and muscle pain, similar to the findings of previous studies64.

Currently, fish are already examined for the presence of ciguatera65 through more scientific analysis without considering the role of understanding the ecology of ciguatera. Current knowledge on ciguatera needs to be confirmed through field studies, as natural conditions can produce different responses than laboratory-controlled conditions1. This valuable suggestion can integrate all levels of the ITK for the CFP, from identifying ecological triggers to understanding its exposure to humans and managing ciguatera with science. The people’s ecological understanding of ciguatera in the area differed from the data collected, which confirmed that approximately 84% (n = 31) of participants were exposed to ciguatera by consuming reefs or offshore fish. All the participants reported using local treatments to alleviate their symptoms of ciguatera.

The Vanuatu National Policies and Plans66,67,68,69,70,71 acknowledge and recognize ITK as a tool for environmental management and disaster risk reduction. However, there are limited effort from communities to develop their respective environmental management plans that will be integrated with traditional knowledge for future generations72. The findings of this research can be used to develop communities management plan that will implement sectoral policies related to climate change and disaster risk reduction, the Climate Services Framework, the Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction Policy, and the Fisheries and Public Health Policies. This can be possible by integrating different sectoral information and data with the ITK to develop a platform that bridges the information gap between the ITK and science and improves how government agencies and communities monitor environmental change for successful response and adaptation.

ITK is crucial for the Ambae Island and Vanuatu people to monitor ecological factors that could trigger the presence of ciguatera. Specifically, this study highlights the importance of the ITK in monitoring environmental changes and its integration with science to predict the presence of ciguatera. The paper concludes that national government agencies and scientists must work more closely with communities to find best practices to integrate the ITK with science to sustain ITK sustainability as a valued tool for monitoring environmental changes. This approach will continue to support the monitoring of the environment and enable effective response and adaptation to environmental and climate change. It is important to note that these findings may apply to any islands with volcanoes and similar geographies to Ambae Island.

Study site and methods

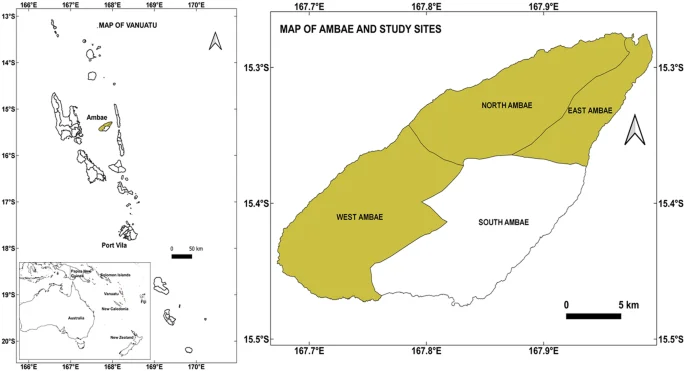

Study site

Ambae is a volcanic island that experienced volcanic eruptions in 2017, forcing the entire population to evacuate to the neighboring Pentecost, Maewo, and Santo Islands. We conducted the research in three area councils on the island—the east, north, and west area councils (Fig. 6). We chose these locations because there has been limited research on social-eco-environmental challenges in these areas. The interaction between people and the environment has become a challenge, particularly in terms of marine resources, due to an increase in the number of ciguatera cases. The province of Penama, which comprises Ambae, Pentecost, and Maewo Island, has recorded the highest number of Ciguatera cases in the last ten years in Vanuatu73. The East and West area councils have some access to government services, while the North area council has limited government services. Most of the main creeks on the island are located in the North area council, which acts as a conduit for sediment transportation to the coast and into the ocean during extreme rainfall events.

Map of Vanuatu with Ambae Island Area Councils highlighted in dark yellow.

Methods

Our research project used a mixed-methods approach to collect data from three area councils on Ambae. Four parts of the research interview questions were used to gather quantitative and qualitative data. For this paper, the quantitative data were derived from research question part 2 A (2), while the qualitative data were derived based on research question parts 2B (1) and 4 and 4B (3) (Supplementary Table 3). The interview questions asked the participants about their perception of the importance of the ITK to them (value of ITK), the different ecological factors they observed in the environment that indicate the CFP season (ecological indicators), and their understanding of CFP (ecology of Ciguatera). These questions help individuals extract cultural knowledge, promote research relevance, and build positive relationships with the community74,75,76, allowing us to gain a deeper understanding of the ecological indicators of environmental changes77. The method used allows for a richer understanding of the application of the ITK in predicting ciguatera outbreaks. Moreover, it could offer valuable insights into translating ITK into quantitative facts for environmental policy and decision-making78.

The study involved thirty-seven individuals, consisting of twenty-eight males and nine females. The participants were chosen from various backgrounds: chiefs, heads of household, farmers, fishermen, women, church leaders, and government officials such as teachers, health workers, and agriculture field officers. The selection process was carried out by a resident who had lived in the area for an extended period and had known people with knowledge and experience using the ITK to predict potential ciguatera outbreaks. Of all the participants, 65% (n = 24) had resided in the area for over 20 years, and eleven had lived there for over forty years. The West Ambae Area Council was represented by eleven individuals, the North Ambae Area Council with ten participants, and thirteen from the East Ambae Area Council.

Interviews, which were approximately one hour long, were conducted by the lead author with support from a field assistant in late 2023 and took place in participants’ homes to ensure privacy. All interviews were recorded on paper and audio. The lead author later transcribed the audio-recorded interviews and translated them into English. The paper-recorded interviews were later sorted and ready for analysis (the original interviews were conducted in Bislama, a national language for Vanuatu). The quantitative data set was analyzed using Microsoft Excel, and thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data.

When analyzing data, we followed the six-step process of thematic analysis26,29,79,80,81. This process helps us identify patterns within the data that relate to participants’ experiences, specifically how they value ITK to predict and manage environmental risks. We conclude with three main themes: how local people value the ITK in monitoring environmental changes, the different local ecological indicators they use to predict CFP outbreaks, and their understanding of the ecology of CFP. The themes emphasized the role of the ITK in predicting ciguatera outbreaks and provided a richer understanding of its application.

We reviewed several national, regional, and international policies and plans82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90. Several policy objectives were not directly related to integrating ITK and science. However, they emphasized the use of ITK in response to and adaptation to environmental and climate changes35,67,68,69,70,71 and possibly the use of ITK in parallel with science33. Other policies related to the health implications of decisions made by different sectors related to adaptation planning in the health sector have concentrated mainly on traditional knowledge practices related to seafood consumption practices35. The information collected from the review was tabulated (Supplementary Table 2) to provide reference during the development of an early warning platform and the implementation of the overall framework of the early warning system in Vanuatu.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during this current study are available in the figshare database, https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Data_for_Manuscript_xlsx/27642969.

References

-

Dickey, R. W. & Plakas, S. M. Ciguatera: a public health perspective. Toxicon 56, 123–136 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Chinain, M., Gatti, C. M. I., Darius, H. T., Quod, J. P. & Tester, P. A. Ciguatera poisonings: a global review of occurrences and trends. Harmful Algae. 102, 101873 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Gaiani, G., Diogène, J., Campàs, M. Addressing ciguatera risk using biosensors for the detection of gambierdiscus and ciguatoxins. in Biosensors for the Marine Environment: Present and Future Challenges (eds Regan F., Hansen P. D., Barceló D) (Springer International Publishing, 2023).

-

Hales, S., Weinstein, P. & Woodward, A. Ciguatera (Fish Poisoning), El Niño, and Pacific Sea Surface Temperatures. Ecosyst. Health 5, 20–25 (1999).

Google Scholar

-

Longo, S., Sibat, M., Darius, H. T., Hess, P. & Chinain, M. Effects of pH and Nutrients (Nitrogen) on Growth and Toxin Profile of the Ciguatera-Causing Dinoflagellate Gambierdiscus polynesiensis (Dinophyceae). Toxins 12, 767 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Raab, H. et al. Confirmation of fishers’ local ecological knowledge of ciguatoxic fish species and ciguatera-prone hotspot areas in Puerto Rico using harmful benthic algae surveys and fish toxicity testing. bioxiv 2021-10 (2021).

-

Lako, J. V., Naisilisili, S., Vuki, V. C., Kuridrani, N. & Agyei, D. Local and traditional ecological knowledge of fish poisoning in Fiji. Toxins 15, 223 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Inaotombi, S. & Mahanta, P. C. Pathways of socio-ecological resilience to climate change for fisheries through indigenous knowledge. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 25, 2032–2044 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Akanbi A. K. & Masinde M. Towards the development of a rule-based drought early warning expert systems using indigenous knowledge. In: 2018 International Conference on Advances in Big Data, Computing and Data Communication Systems (icABCD). (ieeexplore.ieee.org, 2018).

-

Alessa, L. et al. The role of Indigenous science and local knowledge in integrated observing systems: moving toward adaptive capacity indices and early warning systems. Sustain. Sci. 11, 91–102 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Hermans, T. D. G. et al. Exploring the integration of local and scientific knowledge in early warning systems for disaster risk reduction: a review. Nat. Hazards 114, 1125–1152 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Masinde, M. An effective drought early warning system for Sub-Saharan Africa: integrating modern and indigenous approaches. In Proc. Southern African Institute for Computer Scientist and Information Technologists Annual Conference 2014 on SAICSIT 2014 Empowered by Technology. SAICSIT ’14. Association for Computing Machinery; 60–69 (dl.acm.org, 2014).

-

Okonya J. S. & Kroschel J. Indigenous knowledge of seasonal weather forecasting: a case study in six regions of Uganda. Agric. Sci. 2013. https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2013.412086 (2013).

-

Rarai, A., Parsons, M., Nursey-Bray, M. & Crease, R. Situating climate change adaptation within plural worlds: the role of Indigenous and local knowledge in Pentecost Island, Vanuatu. Environ. Plann. E Nat. Space 5, 2240–2282 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Becker, J., Johnston, D., Lazrus, H., Crawford, G. & Nelson, D. Use of traditional knowledge in emergency management for tsunami hazard: a case study from Washington State, USA. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 17, 488–502 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

McAdoo, B. G., Moore, A. & Baumwoll, J. Indigenous knowledge and the near field population response during the 2007 Solomon Islands tsunami. Nat. Hazards 48, 73–82 (2009).

Google Scholar

-

Syafwina Recognizing indigenous knowledge for disaster management: smong, early warning system from Simeulue Island, Aceh. Procedia Environ. Sci. 20, 573–582 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Walshe, R. A. & Nunn, P. D. Integration of indigenous knowledge and disaster risk reduction: a case study from Baie Martelli, Pentecost Island, Vanuatu. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 3, 185–194 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Daniel, D., Satriani, S., Zudi, S. L. & Ekka, A. To what extent does indigenous local knowledge support the social–ecological system? A case study of the ammatoa community, Indonesia. Resources 11, 106 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Abbott, D. & Wilson, G. Lived experience and the advocates of local knowledge. in The Lived Experience of Climate Change: Knowledge, Science and Public Action (eds Abbott, D, & Wilson, G) (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

-

Nursey-Bray, M. & Parsons, M. Indigenous Peoples and Climate Change: Australia and New Zealand. in Climate Action (eds Leal Filho W, Azul A. M., Brandli L., Özuyar P. G., Wall T) (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

-

Macherera, M. & Chimbari, M. J. Developing a community-centred malaria early warning system based on indigenous knowledge: Gwanda District, Zimbabwe: original research. Jamba. J. Disaster Risk Stud. 8, 1–10 (2016).

-

Maphane, D., Ngwenya, B. N., Motsholapheko, M. R., Kolawole, O. D. & Magole, L. Rural livelihoods and community local knowledge of risk of malaria transmission in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Botsw. Notes Rec. 49, 136–152 (2017).

-

Bohensky, E. L. & Maru, Y. Indigenous knowledge, science, and resilience: what have we learned from a decade of international literature on “Integration”? Ecol. Soc. 16 (2011). accessed 26 March 2024. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268978.

-

Ocholla, D. Marginalized knowledge: an agenda for indigenous knowledge development and integration with other forms of knowledge. Int. Rev. Inf. Ethics 7, 236–245 (2007).

-

Hutchinson, P. et al. Maintaining the integrity of Indigenous knowledge; sharing Metis knowing through mixed methods. Int. J. Crit. Indigenous Stud. 7, 1–14 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Ogunniyi, M. B. The challenge of preparing and equipping science teachers in higher education to integrate scientific and indigenous knowledge systems for learners: the practice of higher education. South Afr. J. High. Educ. 18, 289–304 (2004).

-

Matsui, K. Problems of defining and validating traditional knowledge: a historical approach. Int. Indigenous Policy J. 6, 1–25 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Mercer, J., Kelman, I., Taranis, L. & Suchet-Pearson, S. Framework for integrating indigenous and scientific knowledge for disaster risk reduction. Disasters 34, 214–239 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Buell, M. C., Ritchie, D., Ryan, K. & Metcalfe, C. D. Using indigenous and western knowledge systems for environmental risk assessment. Ecol. Appl. 30, e02146 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Kniveton, D. et al. Dealing with uncertainty: integrating local and scientific knowledge of the climate and weather. Disasters 39, s35–s53 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Aberra, A. G. et al. Incorporating other worldviews such as Indigenous knowledge will strengthen environmental risk assessments. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 19, 847–849 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

User S. 2009 NPH Census. Published June 24, 2020. accessed 17 May 2023. https://vnso.gov.vu/index.php/en/census-and-surveys/census/national-population-housing-census/2009-census.

-

26-June-2015-MSG-2038-Prosperity-for-All-Plan-and-Implementation-Framework.pdf. accessed 9 Apr 2024. https://www.msgsec.info/wp-content/uploads/publications/26-June-2015-MSG-2038-Prosperity-for-All-Plan-and-Implementation-Framework.pdf.

-

Location of Vanuatu Fisheries Departmnt. Google My Maps. accessed 9 Apr 2024. https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1vwlpB1UiwokXB8cjMqLhfHdoB5Bj68dW.

-

Costa, O. S., Attrill, M. J. & Nimmo, M. Seasonal and spatial controls on the delivery of excess nutrients to nearshore and offshore coral reefs of Brazil. J. Mar. Syst. 60, 63–74 (2006).

Google Scholar

-

Cissé, G., et al. Health, wellbeing and the changing structure of communities. in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Pörtner H. O., Roberts D. C., Tignor M. M. B., et al.), (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

-

Chan, E. Y. Y., Guo, C., Lee, P., Liu, S. & Mark, C. K. M. Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (Health-EDRM) in remote ethnic minority areas of rural China: the case of a flood-prone village in Sichuan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 8, 156–163 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Son, H. N., Kingsbury, A. & Hoa, H. T. Indigenous knowledge and the enhancement of community resilience to climate change in the Northern Mountainous Region of Vietnam. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 45, 499–522 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Wheeler, H. & Root-Bernstein, M. Informing decision‐making with Indigenous and local knowledge and science. J. Appl. Ecol. 57. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13734 (2020).

-

Fernández-Llamazares, Á. et al. An empirically tested overlap between indigenous and scientific knowledge of a changing climate in Bolivian Amazonia. Reg. Environ. Change 17, 1673–1685 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Luther, J. et al. World Meteorological Organization (WMO)—Concerted International Efforts for Advancing Multi-hazard Early Warning Systems. in. Advancing Culture of Living with Landslides (eds Sassa, K., Mikoš, M. & Yin, Y), (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

-

Pham, M., Thieken, A. & Bubeck, P. Community-based early warning systems in a changing climate: an empirical evaluation from coastal central Vietnam. Clim. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2024.2307398 (2024).

-

Niroa, J. J. & Nakamura, N. Volcanic disaster risk reduction in indigenous communities on Tanna Island, Vanuatu. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 74, 102937 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bardosh, K. L., Ryan, S. J., Ebi, K., Welburn, S. & Singer, B. Addressing vulnerability, building resilience: community-based adaptation to vector-borne diseases in the context of global change. Infect. Dis. Poverty 6, 166 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Zavaleta-Cortijo, C. et al. Indigenous knowledge, community resilience, and health emergency preparedness. Lancet Planet. Health 7, e641–e643 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Adade Williams, P., Sikutshwa, L. & Shackleton, S. Acknowledging indigenous and local knowledge to facilitate collaboration in landscape approaches—lessons from a systematic review. Land 9, 331 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Avery, L. M. Rural science education: valuing local knowledge. Theory Into Pract. 52, 28–35 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

MACKINSON, S. Integrating local and scientific knowledge: an example in fisheries science. Environ. Manag. 27, 533–545 (2001).

Google Scholar

-

Mauro, F. & Hardison, P. D. Traditional knowledge of indigenous and local communities: international debate and policy initiatives. Ecol. Appl. 10, 1263–1269 (2000).

Google Scholar

-

Naess, L. O. The role of local knowledge in adaptation to climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 4, 99–106 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Danielsen, F. et al. The value of indigenous and local knowledge as citizen science. in Citizen Science – Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy (eds Hecker S., Haklay M., Bowser A., Makuch Z., Vogel J., Bonn A), (UCL Press, 2018).

-

Leal Filho, W. et al. The role of indigenous knowledge in climate change adaptation in Africa. Environ. Sci. Policy 136, 250–260 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

McMillen, H. L. et al. Small islands, valuable insights: systems of customary resource use and resilience to climate change in the Pacific. Ecol. Soc. 19 (2014). Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269694.

-

Popovici, R. et al. How do Indigenous and local knowledge systems respond to climate change? ES 26, art27 (2021).

-

Reyes-García, V. et al. A collaborative approach to bring insights from local observations of climate change impacts into global climate change research. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 39, 1–8 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Schlingmann, A. et al. Global patterns of adaptation to climate change by indigenous peoples and local communities. A systematic review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 51, 55–64 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

André, L. V. et al. A framework for mapping local knowledge on ciguatera and artisanal fisheries to inform systematic conservation planning. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 78, 1357–1371 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Friedman, M. A. et al. Ciguatera fish poisoning: treatment, prevention and management. Mar. Drugs 6, 456–479 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Pacific Community, Division of Fisheries, Aquaculture and Marine Ecosystems, Information Section, BP D5, 98848 Noumea Cedex, New Caledonia (2018).

-

Schils, T. Episodic Eruptions of Volcanic Ash Trigger a Reversible Cascade of Nuisance Species Outbreaks in Pristine Coral Habitats. PLOS One. 7, e46639 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

ndmo-ambae-volcano-operational-summary-and-review-report-2017.pdf. accessed 12 March 2024. https://ndmo.gov.vu/images/download/VolcanoActivity-ambrym-ambae/lessons-learnt-report/ndmo-ambae-volcano-operational-summary-and-review-report-2017.pdf.

-

Vroom, P. S. & Zgliczynski, B. J. Effects of volcanic ash deposits on four functional groups of a coral reef. Coral Reefs. 30, 1025–1032 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Witt, V. et al. Volcanic ash supports a diverse bacterial community in a marine mesocosm. Geobiology 15, 453–463 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Argyle, P. A. et al. Diversity and distribution of benthic dinoflagellates in Tonga include the potentially harmful genera Gambierdiscus and Fukuyoa. Harmful Algae. 130, 102524 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Sparrow, L. & Heimann, K. Key environmental factors in the management of ciguatera. J. Coast. Res. 75, 1007–1011 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Chinain, M., Gatt, I. C. M., Roué, M. & Darius, H. T. Ciguatera-causing dinoflagellates in the genera Gambierdiscus and Fukuyoa: Distribution, ecophysiology and toxicology. In Dinoflagellates: Morphology, Life History and Ecological Significance (ed. Subba Rao, D. V.) 405–457 (2020).

-

Vanuatu_National_Ocean_Policy_High_Res_020616.pdf. accessed 19 Jul 2024. https://macbio-pacific.info/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Vanuatu_National_Ocean_Policy_High_Res_020616.pdf.

-

Rantes, J. The Challenges of Integrating Sustainable Development into Policy and Practice: A Case Study from Vanuatu (Southwest Pacific). PhD Thesis. University of the Sunshine Coast, Queensland; 2019. accessed 27 June 2024. https://research.usc.edu.au/view/pdfCoverPage?instCode=61USC_INST&filePid=13139329310002621&download=true.

-

User S. Health Policies. Ministry of Health. Published November 10, 2018. accessed 19 July 2024. https://moh.gov.vu/index.php/pages/health-policies.

-

National Fisheries policy FINAL FINAL FINAL_0.pdf. accessed 19 Jul 2024. https://www.nab.vu/sites/default/files/documents/National%20Fisheries%20policy%20FINAL%20FINAL%20FINAL_0.pdf.

-

Tait, A. & Macara, G. Vanuatu Framework for Climate Services. Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP), National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd (NIWA), Government of the Republic of Vanuatu (2016).

-

Vanuatu National CCDRR Policy 2022 -2030 (2nd Edition) | National Advisory Board. accessed 19 Jul 2024. https://www.nab.vu/document/vanuatu-national-ccdrr-policy-2022-2030-2nd-edition.

-

Community Health Services. Ministry of Health. accessed 12 Mar 2024. https://moh.gov.vu/index.php/public-health/community-health-services.

-

Molina-Azorín, J. F. & López-Gamero, M. D. Mixed methods studies in environmental management research: prevalence, purposes and designs. Bus. Strategy Environ. 25, 134–148 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Kinnebrew, E., Shoffner, E., Farah-Pérez, A., Mills-Novoa, M. & Siegel, K. Approaches to interdisciplinary mixed methods research in land-change science and environmental management. Conserv. Biol. 35, 130–141 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Botha, L. Mixing methods as a process towards indigenous methodologies. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 14, 313–325 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Chilisa, B. & Tsheko, G. N. Mixed methods in indigenous research: building relationships for sustainable intervention outcomes. J. Mixed Methods Res. 8, 222–233 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Trainor, A. A. & Graue, E. Reviewing Qualitative Research in the Social Sciences. (Routledge, 2013).

-

Flick, U. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research design. 1-100 (Online Digital Bookstore, Torrossa, 2022).

-

Clarke, V. & Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 297–298 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

SPREP Strategic Plan 2017-2026 | Pacific Environment. accessed 19 Jul 2024. https://www.sprep.org/publications/sprep-strategic-plan-2017-2026.

-

Strengthening Pacific health systems. accessed 19 Jul 2024. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/activities/strengthening-pacific-health-systems.

-

Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform our World | United Nations. accessed 19 Jul 2024. https://www.un.org/en/exhibits/page/sdgs-17-goals-transform-world.

-

National CCDRR Policy 2022−2030.pdf. accessed 10 Apr 2024. https://www.nab.vu/sites/default/files/documents/National%20CCDRR%20Policy%202022-2030.pdf.

-

National Fisheries policy FINAL FINAL FINAL_0.pdf. accessed 10 Apr 2024. https://www.nab.vu/sites/default/files/documents/National%20Fisheries%20policy%20FINAL%20FINAL%20FINAL_0.pdf.

-

Vanuatu2030-EN-FINAL-sf.pdf. accessed 10 Apr 2024. https://www.gov.vu/images/publications/Vanuatu2030-EN-FINAL-sf.pdf.

-

Vanuatu_National_Ocean_Policy_High_Res_020616.pdf. accessed 10 Apr 2024. https://macbio-pacific.info/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Vanuatu_National_Ocean_Policy_High_Res_020616.pdf.

-

User S. Strategic Plan. accessed 10 Apr 2024. https://docc.gov.vu/index.php/resources/publications/strategic-plan.

-

World Health Organization. Human Health and Climate Change in Pacific Island Countries. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; 2015.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all the participants in this research. This study is supported by the Association of the Commonwealth Universities (ACU) throught the Ocean Country Partnership Programme Scholarship (OCPP) offered to the lead author. The University of the South Pacific hosted the lead author in Suva, Fiji Islands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Allan Rarai: Conceptualization, Investigation and data collection, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing Original Draft, Writing – review and editing; John Ruben: Data collection, Review and Edit; Meg Parsons: Writing – Review and Editing, and Eberhard Weber: Writing – Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Dominic Kniveton and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ida N. S. Djenontin and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Peer Review File

Supplementary Information

Reporting Summary

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rarai, A., Weber, E., Ruben, J. et al. Indigenous knowledge with science forms an early warning system for ciguatera fish poisoning outbreak in Vanuatu.

Commun Earth Environ 5, 761 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01931-5

-

Received: 18 April 2024

-

Accepted: 25 November 2024

-

Published: 13 December 2024

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01931-5