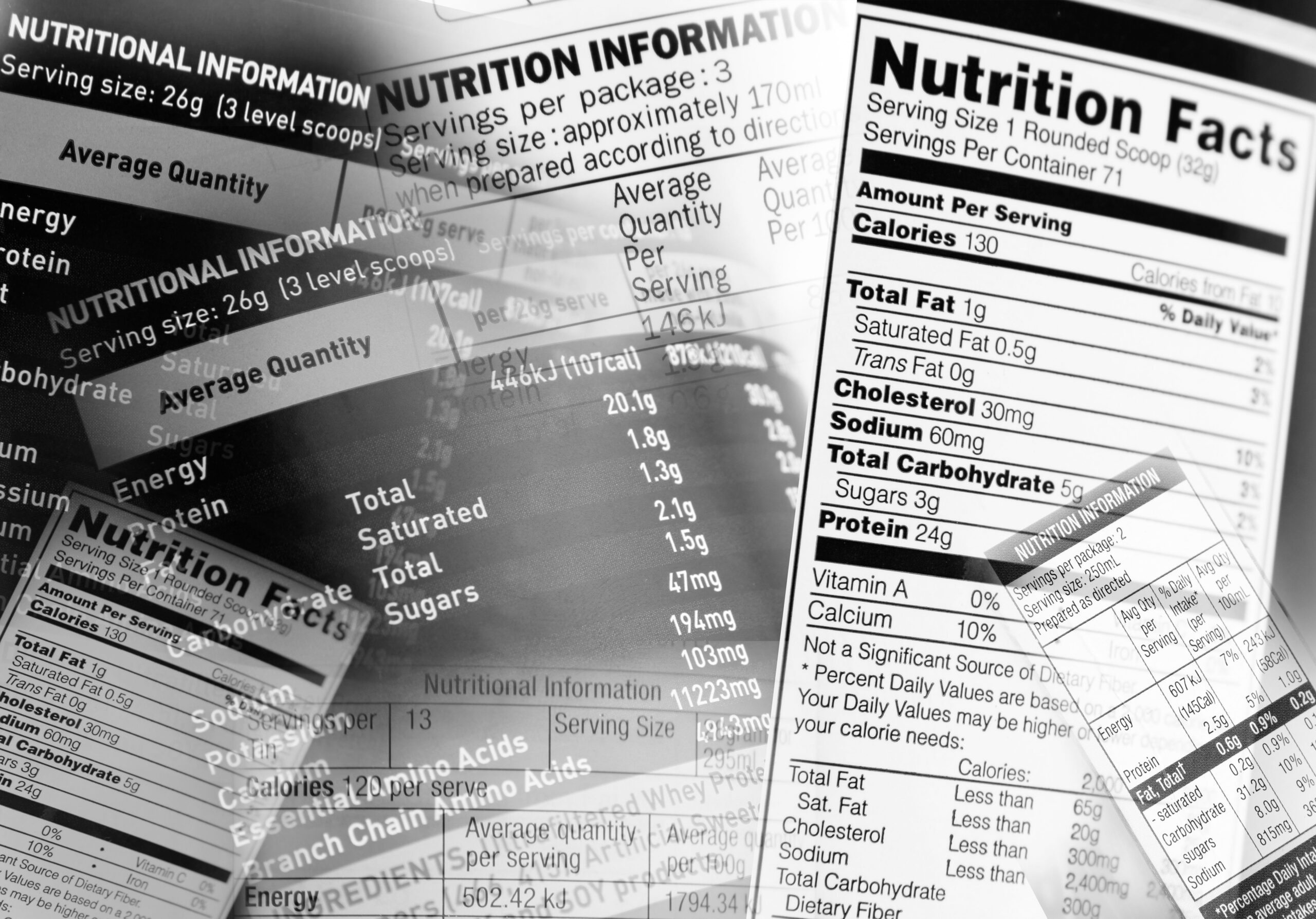

The FDA announced a proposed requirement for front-of-package nutrition labels for most packaged food. If finalized, the requirement would necessitate readily available nutrition information, including saturated fat, sodium, and added sugar content. As part of the nutrition label, saturated fats, sodium, and added sugars would be categorized as “Low,” “Med,” and “High” and would complement the FDA’s Nutrition Facts label. The proposal is part of the FDA’s initiative to combat chronic diseases in the United States.1

Obesity, Diabetes, Hypertension, Cardiovascular Diseases, Nutrition, FDA | Image Credit: Stillfx | stock.adobe.com

“The science on saturated fat, sodium and added sugars is clear,” Robert M. Califf, MD, commissioner of the FDA, said in a news release. “Nearly everyone knows or cares for someone with a chronic disease that is due, in part, to the food we eat. It is time we make it easier for consumers to glance, grab, and go. Adding front-of-package nutrition labeling to most packaged foods would do that. We are fully committed to pulling all the levers available to the FDA to make nutrition information readily accessible as part of our efforts to promote public health.”1

Food, as stated by Jim Jones, deputy commissioner for human foods at the FDA, in the news release, should not contribute to chronic diseases, but rather, should be for wellness. Nutrition is not only an essential part of wellness but can help improve the efficacy of medication. The Nutrition Info box is part of the White House National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, which is aimed to reduce diet-related diseases by 2030. As such, nutrition is related to diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity. Obesity, specifically, has been found to have a positive and significant effect on the prevalence of chronic diseases, with greater probability of having hypertension (35%), hyperlipidemia (28%), and diabetes (11%) for those who are obese.1,2

To determine the effectiveness of the Nutrition Info box, the FDA conducted an experimental study that included approximately 10,000 adults in the US. The FDA aimed to explore the consumer responses to the 3 different types of front-of-package labels and determine which was the quicker and more accurate assessment of the healthfulness of the product. Included were 2 independent experimental tasks that were run sequentially and built into a 15-minute online questionnaire.1,3

For the first task, the participants viewed 3 nutritional profiles, one being the healthiest, one being the middle, one being the least, and were asked to select the most and least healthy of the 3. In the second task, the participants viewed front-of-package scheme that varied by nutrient profile—cereal, frozen meal, canned soup—and answered questions about the product and the label. Questions ranged from perception of healthfulness, nutrient content, and attitude toward the scheme.3

The FDA tested 8 schemes, with 1 using the Guideline Daily Amount (GDA), which included attributes of the “Facts Up Front” scheme, 5 using “Nutrition Info,” which mimicked the Nutrition Facts label design and high, medium, and low designations, and 2 using “High In,” which listed only the nutrients that had the percent of Daily Value of 20% of higher, according to the authors of the study. All labels were tested in the upper right of the product label, with the exception of one on the lower right corner.3

Investigators found that patients viewing the High In labels were significantly less likely to correctly identify the healthiest and least healthy mock food and took longer to answer the questions. Further, the ratings on attitude and perception questions were significantly lower for the High in compared to the other 2 types of labels. When comparing level of nutrients to limit, those viewing the GDA scheme were less likely to characterize the levels correctly. For the 5 Nutrition Info labels, investigators found that none outperformed the other across all measurements, and patients were generally able to correctly characterize the level of the nutrition in the various product. The FDA also found that the black and white versions performed best in several instances.3

If finalized, food manufacturers are required to add a Nutrition Info box to most packaged food products 3 years after the final rule’s effective date for businesses with $10 million or more in annual food sales and 4 years for manufacturers making less than $10 million in food sales. As part of the White House National Strategy, the FDA is working to develop a “healthy” symbol and are drafting a phase 2 voluntary sodium reduction target.1