Abstract

Science is crucial for evidence-based decision-making. Public trust in scientists can help decision makers act on the basis of the best available evidence, especially during crises. However, in recent years the epistemic authority of science has been challenged, causing concerns about low public trust in scientists. We interrogated these concerns with a preregistered 68-country survey of 71,922 respondents and found that in most countries, most people trust scientists and agree that scientists should engage more in society and policymaking. We found variations between and within countries, which we explain with individual- and country-level variables, including political orientation. While there is no widespread lack of trust in scientists, we cannot discount the concern that lack of trust in scientists by even a small minority may affect considerations of scientific evidence in policymaking. These findings have implications for scientists and policymakers seeking to maintain and increase trust in scientists.

Main

Public trust in science provides many benefits to society. It helps people make informed decisions (for example, on health and nutrition) on the basis of the best available evidence, provides the foundation for evidence-based policymaking and facilitates government spending on research. Trust in science and scientists enables the management of global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change. Societies with high public trust in science and scientists dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic more effectively, as citizens were more likely to comply with non-pharmaceutical COVID-19 interventions1 and had higher vaccine confidence2. People with high trust in scientists are also more likely to engage in individual and collective action on climate change3,4.

Studies find that most people trust science, and scientists are among the most trusted actors in society5,6,7. Despite these findings, there is a popular dominant narrative claiming that there is a crisis of trust in science and scientists8,9. This narrative well predates the COVID-19 pandemic and may alter people’s views about scientists10,11,12. It is therefore important to revisit this narrative and provide robust empirical evidence on whether it is accurate.

Most previous studies have been limited to the Global North, typically the USA or Europe, including our own previous work (see, for example, refs. 13,14,15,16,17,18,19). A few studies have gone beyond these regions5,6,7,20,21,22,23. However, they assess a limited range of theoretical constructs. We address this limitation in two ways. First, we analyse the extent to which people believe that scientists should be involved in society and policymaking. We refer to this as ‘normative perceptions of science in society and policymaking’. Second, we investigate which issues people want scientists to prioritize in their work and how such perceptions are related to their trust in scientists. Previous studies have shown that trust is affected by the perception of value alignment24. People who feel that their concerns and values are not reflected in the priorities of scientists may therefore doubt the trustworthiness of scientists.

Our large-scale, preregistered survey expands and strengthens previous work by offering a comprehensive dataset on trust in scientists after the COVID-19 pandemic16 and by investigating the public’s normative perceptions of the role of scientists in society and policymaking and their desired research priorities. We use a theoretically informed multidimensional trust measure25 and examine relevant demographic, ideological, attitudinal and country-level factors to explain trust across countries6. We survey countries and individuals that are underrepresented in research26, and, in almost all countries, we have worked with local research partners27,28.

Our study answers the following questions. (1) How much do people around the world trust scientists, and how do levels of trust vary across countries? (2) How do demographic, ideological, attitudinal and country-level factors relate to trust in scientists (see Supplementary Fig. 1a for a directed acyclic graph), and how do these relationships vary between countries? (3) What are people’s normative perceptions of scientists in society and policymaking, and how do they differ across countries? (4) What issues do people want scientists to prioritize, and do they believe that scientists actually address these priorities? See the preregistration for more detailed research questions and hypotheses (https://osf.io/9ksrj/).

By investigating trust in scientists, we do not mean to imply that trust is always warranted. In some situations, low trust may be warranted. For example, science’s fraught historical relationship with racism, its role in perpetuating racialized forms of knowledge production, sustaining racial paradigms29 and disregarding ethical canons by experimenting on non-white human subjects30, has reduced research participation in some populations31. Furthermore, the epistemic authority of science and scientists has been challenged by misinformation and disinformation32,33, a “reproducibility crisis”34, conspiracy theories35,36 and science-related populist attitudes37,38. Science-related populism has been conceptualized as a perceived antagonism between ‘the ordinary people’ and common sense on one side and academic elites and scientific expertise on the other37. Unlike political populism, which criticizes political elites and their political power claims, science-related populism criticizes academic elites, challenges their decision-making authority in scientific research and suggests that their epistemic truth claims are inferior to the common sense of ‘the people’37. Anti-science attitudes, even if held by only a minority of people, raise concerns about a potential crisis of trust in science, which could challenge the epistemic authority of science and the role of scientists in supporting evidence-based policymaking20,37. These concerns, which have been prominently discussed in leading news media, have been exacerbated as trust in scientists and their desired role in policymaking have become divided along partisan lines. Several studies show that in the USA and some other countries, conservatives and right-leaning individuals have low levels of trust in scientists, hold stronger anti-science attitudes and express low confidence that scientists act in the best interest of the public, provide benefits to society and apply reliable methods19,20,21,39,40. Empirical evidence is needed to determine how widespread such critical attitudes towards science are across countries and population groups.

Our survey goes beyond commonly studied correlates of trust in scientists in four important ways. First, we investigate how trust in scientists relates to science-related populist attitudes. Science-related populists deny that scientists are knowledgeable experts and believe that they do not act in the interest of the general public—two key aspects of trust in scientists37. Second, we investigate whether trust in scientists is related to people’s social dominance orientation (SDO), which has been defined as “the degree to which individuals desire and support group-based hierarchy and the domination of ‘inferior’ groups by ‘superior’ groups”41 (p. 48). Individuals high in SDO are arguably less likely to trust scientists, as they perceive universities as hierarchy-attenuating social institutions42. Previous research supports this, showing that high SDO is a predictor of low trust in scientists43 and distrust in climate science19,43. However, it is unknown how SDO relates to trust in scientists across many countries. Third, we investigate what goals people want scientists to prioritize in their work and how this relates to trust. Fourth, we investigate whether people perceive that their desired priorities are tackled by science.

To answer our research questions, we conducted a crowdsourced Many Labs project with the same translated online questionnaire given to 71,922 respondents in 68 countries on all inhabited continents (Supplementary Fig. 2). The term ‘country’ in this Article refers to both sovereign states and territories not recognized as such. The survey covered 31% of the world’s countries, which together make up 79% of the global population. The data were collected between November 2022 and August 2023, with quota samples that were weighted according to national distributions of age, gender and education level, as well as country sample size. As recommended by other studies on trust in scientists6, we provided the respondents with a definition of science and scientists to mitigate semantic variations across languages (Supplementary Information). We measured trust in scientists (instead of science) because ‘science’ is more abstract than ‘scientists’ and therefore makes a less clear referent: people may think of scientific institutions, scientific communities, scientific methods or individual scientists when being asked about their general perception of ‘science’. However, these trust measures can be distinguished both conceptually and empirically25,44. For example, research has shown that less educated people trust scientific methods more than scientific institutions44. General measures that assess trust in the scientific community capture only some of the conceptually established dimensions of perceived trustworthiness (for example, expertise)25. We reduced this ambiguity by avoiding the abstract category ‘science’ and using the more concrete reference object ‘scientists’6. We slightly deviated from the preregistration. We collapsed sparsely populated neighbouring strata for post hoc weighting, excluded confidence in science as a model covariate because of multicollinearity and included SDO as a covariate in the regression model testing predictors of normative perceptions of the role of science in society and politics (Supplementary Information). All analyses can be reproduced with the replication materials available at https://osf.io/wj34h/.

Results

Trust in scientists across the world

We employed an index composed from a 12-item scale measuring four established dimensions of trustworthiness: perceived competence, benevolence, integrity and openness13,25,45. This scale is based on a comprehensive review of trust measures used to assess trustworthiness perceptions of scientists45. It was pretested to confirm its reliability, relies on accepted conceptual assumptions that we validated in factor analyses and has high reliability across countries46. However, confirmatory factor analyses show that we can assume only configural invariance and no metric or scalar invariance46. This is a common caveat of multilingual survey research and is to some extent unavoidable47. When these components of trustworthiness perceptions are aggregated to a single score, the index represents an integrative measure of public trust in scientists with strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.93 and ω = 0.95). We therefore used the aggregate index for our main analyses (see Supplementary Information for additional analyses with individual trust dimensions).

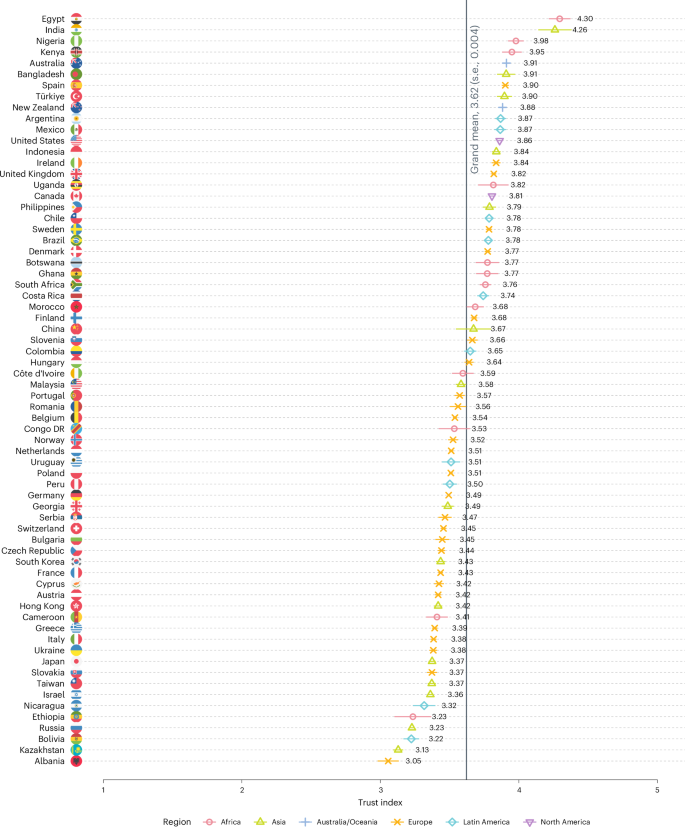

Overall, trust in scientists is moderately high (grand mean, 3.62; s.d., 0.70; 1 = very low, 2 = somewhat low, 3 = neither high nor low, 4 = somewhat high, 5 = very high). No country shows low overall trust in scientists (Fig. 1). Across the globe, people perceive scientists as having high competence (mean, 4.02; s.d., 0.71), with 78% believing that scientists are qualified to conduct high-impact research (5% believe they are unqualified, and 16% selected the scale midpoint; Supplementary Fig. 3). People perceive scientists to have moderate integrity (mean, 3.58; s.d., 0.78) and benevolent intentions (mean, 3.55; s.d., 0.82; Supplementary Table 1). For example, 57% of people believe that most scientists are honest (11% believe they are dishonest, and 31% selected the scale midpoint), and 56% believe that most scientists are concerned about people’s well-being (15% believe they are not concerned, and 29% selected the scale midpoint). Scientists’ perceived openness to feedback is slightly lower (mean, 3.33; s.d., 0.86), with 42% believing that scientists pay attention to others’ views somewhat or very much. Overall, 75% agree that scientific research methods are the best way to find out whether something is true or false. Trust in scientific methods moderately correlates with trust in scientists (r69,516 = 0.473; P < 0.001; t = 128.45; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.468 to 0.478), supporting previous findings on the multidimensionality of trust in science44.

Total n = 69,527. Country ns range between 312 and 8,014 (see Supplementary Information for a detailed overview). The vertical line denotes the weighted grand mean. The horizontal lines indicate means ± standard errors. Country-level standard errors range between 0.008 and 0.133.

While trust in science is moderately high overall, there are notable variations across countries and regions (Fig. 1). Contrary to previous studies6,7, we did not find a clear pattern that scientists are less trusted in Latin American and African countries. However, we did find patterns within specific regions. For example, Russia as well as several former Soviet republics and satellite states (such as Kazakhstan) show relatively low trust in scientists.

Correlates of trust in scientists

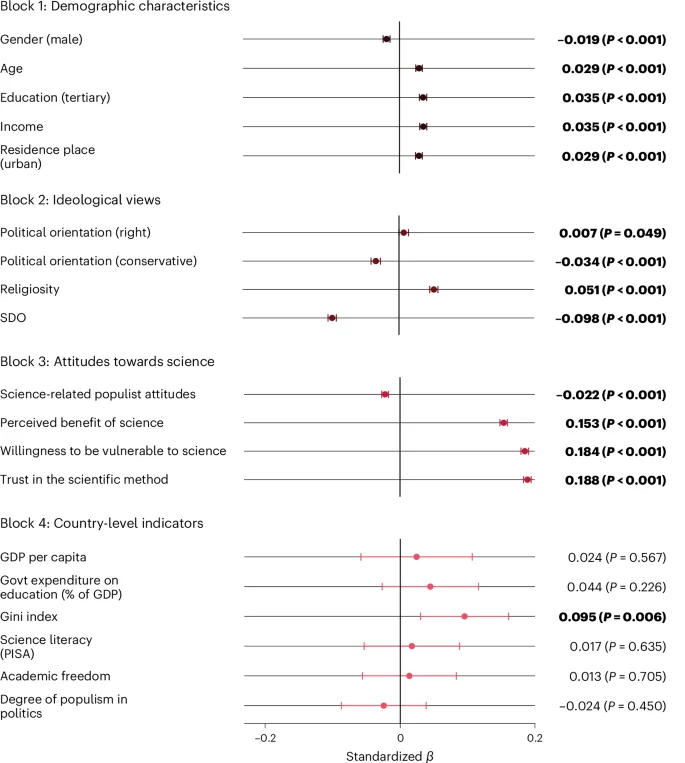

To identify correlates of trust in scientists, we fitted linear random-intercept regression models that included post-stratification weights to provide estimates that are nationally representative in terms of gender, age and education in almost all countries. To investigate how trust in scientists differs across population groups, we assessed several demographic variables and analysed their correlation with trust in scientists. We found higher levels of trust among many demographic groups: women, older people, residents of urban (versus rural) regions, people with high incomes, religious people, educated people, liberal people and left-leaning people (Fig. 2; see also Supplementary Table 2). Differences across countries and sociodemographic groups can be explored with an online data visualization tool developed for this project: https://tisp.shinyapps.io/TISP/.

The dots indicate point estimates of fixed effects, and the horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs based on two-sided t-tests. Estimates for gender (male) indicate the association of identifying as male and trust in scientists, where 0 = female and 1 = male. Estimates for education (tertiary) indicate the association of having tertiary education and trust in scientists, where 0 = no tertiary education and 1 = tertiary education. Estimates for residence place (urban) indicate the association of living in an urban vs rural place of residence, where 0 = rural and 1 = urban. Estimates for political orientation (right) indicate the association of right-leaning vs left-leaning political orientation and trust in scientists, where 1 = strongly left-leaning and 5 = strongly right-leaning. Estimates for political orientation (conservative) indicate the association of conservative vs liberal political orientation and trust in scientists, where 1 = strongly liberal and 5 = strongly conservative. Bold indicates effects significant at P < 0.05. Block 1 uses data from all 68 countries, block 2 uses data from 67 countries (all except Malaysia, where SDO was not measured), block 3 uses data from 66 countries (all except Malaysia and Mexico, where willingness to be vulnerable to science was not measured) and block 4 uses data from 51 countries (all except those where PISA’s literacy scores were not available; Supplementary Information). The full regression results are reported in Supplementary Table 2. The results of exploratory analyses with individual trust dimensions are reported in Supplementary Figs. 4–7. GDP, gross domestic product; Govt, government.

One might assume that trust in science would correlate with tertiary education, as people with more years of schooling and university education have had more chances to build a closer relationship with science and experience the competence and benevolence of scientists, for example48. However, our data show only a small positive relationship between tertiary education and trust in scientists on average (β63,979 = 0.035; P < 0.001; t = 12.56; 95% CI, 0.029 to 0.040). In fact, in most countries we found little or no credible evidence for a relationship between tertiary education and trust (Supplementary Fig. 8). Overall, the relationships between demographic characteristics and trust in scientists are very small (marginal effects plots with unstandardized units are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9).

Many might also assume that religiosity is associated with lower trust in scientists, given that many studies conducted in Global North countries have found this relationship (see, for example, refs. 19,49). However, against this assumption, one previous study found that only 29% of people worldwide believe that science stands in disagreement with their religion6. Another study found that while religiosity is associated with negative attitudes towards science in the USA, the relationship is inconsistent across the world50. Indeed, we found that, overall, religiosity is positively associated with trust in scientists (β47,597 = 0.051; P < 0.001; t = 16.68; 95% CI, 0.045 to 0.057). However, as previous studies have also shown, we found substantive differences across countries and regions50,51. In Muslim countries such as Türkiye, Bangladesh and Malaysia (Supplementary Fig. 10), trust is positively associated with religiosity. Qualitative interviews conducted by the Pew Research Center put these findings into context52. They found that most Muslim participants did not perceive a conflict between science and religion, because their holy text, the Quran, proclaims many principles of science. Conversely, some Christians perceive that science disagrees with their religion, even though there are pronounced variations across countries52. Our findings are consistent with these results.

Other positive correlates of trust in scientists include people’s willingness to rely on scientific advice and thus make themselves vulnerable to scientists, the belief that science benefits people like them, and trust in scientific methods.

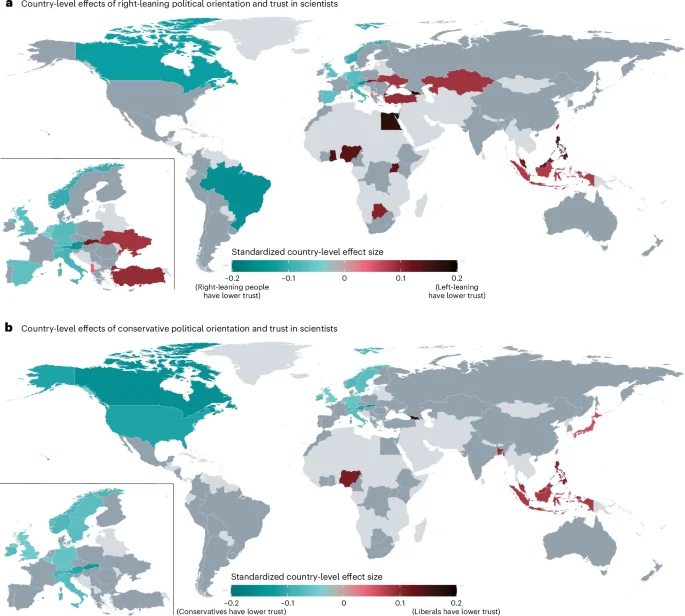

Our study also sheds light on individual attributes that are associated with lower trust in scientists—namely, conservative political orientation, higher SDO and science-populist attitudes. Previous studies, which mostly focused on North America and Europe, have found right-leaning and conservative political orientation to be negatively associated with trust in scientists19,20. Our study partly confirms these findings. We found a negative association between trust and conservative political orientation. However, we found a very small, positive relationship between right-leaning political orientation and trust. Given that some recent global social science studies used a left–right measure to assess political orientation while others used a liberal–conservative measure53,54,55, we used both measures and analysed how the results vary depending on the measure in question. We found that the relationships between the two measures of political orientation and trust vary substantially across countries (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). For example, in the USA, trust is associated with a liberal orientation but not with one’s self-placement on the left–right spectrum. More generally, right-leaning and conservative political orientation are negatively associated with trust in scientists in several European and North American countries, so previous research, which has disproportionally focused on these countries, has tended to stress right-leaning and conservative distrust. However, in most countries (k = 41 for the left–right measure and k = 48 for the liberal–conservative measure), our data do not show credible evidence of a relationship between political orientation and trust in scientists. Furthermore, in some Eastern European, Southeast Asian and African countries, right-leaning individuals have higher trust in scientists. These contrasting findings may be explained by the fact that in some countries right-leaning parties may have cultivated reservations against scientists among their supporters, while in other countries left-leaning parties may have done so56 (Supplementary Fig. 11). In other words, the attitudes of political leadership rather than peoples’ political orientation may better explain politically correlated attitudes towards scientists (see Supplementary Information for selected country-specific explanations). We encourage future research to investigate differences in the two measures of political orientation on the country level (for broader discussions on these measures, see refs. 57,58,59,60).

a,b, Standardized country-level effects of political orientation (in a, 1 = strongly left-leaning to 5 = strongly right-leaning; in b, 1 = strongly liberal to 5 = strongly conservative) on trust in scientists (1 = very low, 3 = neither high nor low, 5 = very high). These effects are sums of the grand effect for political orientation across all countries and the random effect within each country; they were estimated with weighted linear multilevel regressions that contained random intercepts and random slopes for political orientation (left–right in a and liberal–conservative in b) across countries. These models control for demographic characteristics. Two-sided t-tests of the estimates used percentile bootstrapping. Countries with significant country-level effects (P < 0.05) are displayed in colours. Countries coloured in shades of blue show a positive country-level association of left-leaning (a) or liberal (b) orientation and trust in scientists (that is, right-leaning people or conservatives have lower trust). Countries coloured in shades of red show a positive country-level association of right-leaning (a) or conservative (b) orientation and trust in scientists (that is, left-leaning people or liberals have lower trust). Countries with non-significant effects are shaded in dark grey. Countries with no available data are shaded in light grey.

Some studies have looked at SDO—that is to say, a preference for social hierarchy and inequality—and found it to be negatively associated with trust in scientists19,43. Our results confirm this: the low grand mean for SDO (mean, 3.62; s.d., 1.76; 1 = extremely oppose to 10 = extremely favour) is consistent with the overall moderately high trust in scientists. Moreover, we found that those who favour hierarchy enhancement (that is, more strongly endorse SDO) are less likely to trust scientists (β47,602 = −0.098; P < 0.001; t = −31.98; 95% CI, −0.104 to −0.092). This may be because they see universities (that is, scientists) as institutions that weaken social hierarchies42.

We also found that low trust in scientists is associated with science-related populist attitudes—that is, beliefs that people’s common sense is superior to the expertise of scientists and scientific institutions. This corroborates findings on single countries38 and provides evidence that populist resentment against science, a prevalent component of the trust crisis narrative, may undermine public trust in scientists.

We also tested preregistered hypotheses assuming that trust in scientists is linked to country-level indicators, including gross domestic product per capita, PISA’s science literacy score and the Academic Freedom Index. Contrary to the finding of the Wellcome Global Monitor6, we found that trust is weakly correlated with the Gini inequality index (that is, trust is higher in countries with more income inequality). One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the Monitor and our study is that urban populations—which are more likely to trust scientists (Fig. 2)—were overrepresented in our samples from countries with high Gini scores (for example, South Africa). However, a non-preregistered analysis advised against this explanation: the extent of oversampling urban participants (the difference of urban-residence individuals in the sample versus in the population) did not moderate the effect of the Gini index on trust in scientists. We found tentative support for another explanation: the relationship between income inequality and trust (Supplementary Fig. 13) is largely driven by countries with a high degree of corruption (primarily Latin American countries as well as sub-Saharan African countries), as indicated by a significant but very low-powered (1 − β = 0.25 at α = 0.05) interaction effect of the Gini index and Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index61 (Supplementary Table 3). This suggests that people in countries with high inequality may see scientists as a trustworthy alternative to perceivably corrupt governments and political and economic elites62,63,64. Comparing trust in scientists to trust in the national government (based on country estimates from the Wellcome Global Monitor) supports this assumption. Some countries with higher perceived corruption rank considerably lower in trust in the government than in trust in scientists, whereas the opposite applies to less corrupt countries with lower perceived corruption (Supplementary Fig. 14). Overall, we found no credible evidence that trust in the government and trust in scientists are correlated at the country level (r63 = 0.138; P = 0.274; t = 1.104; 95% CI, −0.110 to 0.369). We did not find credible evidence that trust is higher in countries with higher average science literacy scores and government expenditures on education, which challenges assumptions that public understanding of science, and policy measures to increase such understanding, foster trust in scientists65.

Normative perceptions of scientists in society

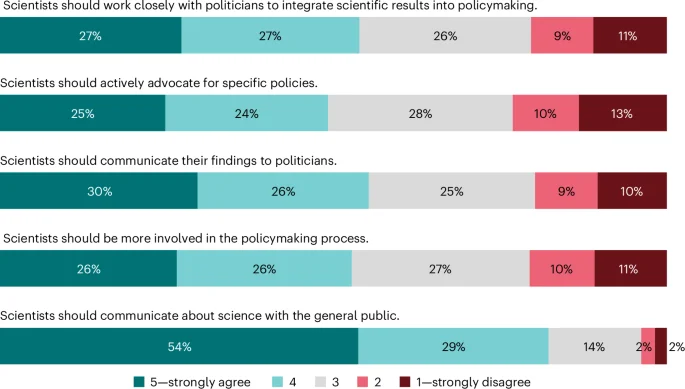

Left–right divides in public opinion about science often centre on the question of whether scientists should take an active role in policymaking66. We found that people tend to agree that scientists should engage in society and policymaking (grand mean, 3.64; s.d., 0.87; 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). In the countries surveyed, a large majority (83%) agree that scientists should communicate about science with the public, particularly in African countries. Overall, only a minority disagree that scientists should actively advocate for specific policies (23%), communicate their findings to politicians (19%) and be more involved in the policymaking process (21%). However, perceptions differ across countries (Supplementary Fig. 15).

About a quarter of the sample selected the scale midpoints, neither agreeing nor disagreeing on whether scientists should be more involved in policymaking and society (Fig. 4). People with high trust in scientists strongly favour scientists’ engagement in society and policymaking (β48 = 0.262; P < 0.001; t = 17.86; 95% CI, 0.232 to 0.291), especially in English-speaking countries (Supplementary Fig. 16). Support for scientists’ engagement in society and policymaking also varies both between and within countries. People who are younger, have tertiary education and higher income, or live in urban areas generally approve of scientists’ engagement in society and policymaking (Supplementary Table 4). Also, right-leaning people and conservatives disapprove of scientists’ engagement in society and policymaking.

Normative perceptions of scientists in society and policymaking using weighted response probabilities.

Perceived and desired priorities of scientific research

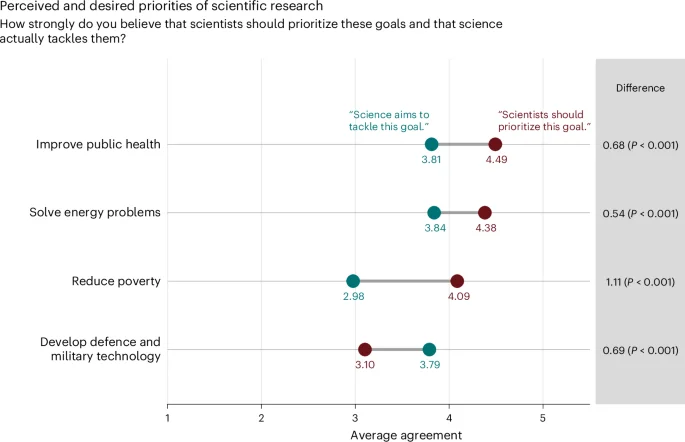

We hypothesized that trust in scientists relates to another normative belief about science: expectations about which societal goals scientists should prioritize67. We compared whether people’s expectations match their perceptions of whether scientists actually tackle the following goals: improving public health, solving energy problems, reducing poverty, and developing defence and military technology.

Overall, people assign the highest priority to improving public health (mean, 4.49; s.d. = 0.84; 1 = low to 5 = high), followed by solving energy problems (mean, 4.38; s.d. = 0.90) and reducing poverty (mean, 4.09; s.d. = 1.10). The responses suggest a substantial discrepancy between what they perceive science is currently prioritizing and what they expect scientists to prioritize, with poverty reduction showing the most substantial discrepancy (Fig. 5). The least desired research goal is developing defence and military technology (mean, 3.10; s.d. = 1.36). Again, there are large differences between global regions (ranging from a mean of 1.88 (s.d. = 1.21) in Uruguay to a mean of 4.07 (s.d. = 1.52) in the Democratic Republic of Congo). In African and Asian countries, people often demand high priority for developing defence and military technology, unlike people in most European and Latin American countries (Supplementary Fig. 17). Overall, people tend to think that science prioritizes developing defence and military technology more than they desire.

The grey horizontal lines indicate the discrepancy between perceived research priorities (“Science aims to tackle this goal”; blue) and desired priorities (“Scientists should prioritize this goal”; red). The P values indicate the results of weighted paired-samples, two-sided t-tests for significant differences between perceived priorities and desired priorities.

Further analyses show that the discrepancy between people’s perceived and desired research priorities is associated with trust in scientists. On the one hand, higher trust is linked to a lower likelihood that scientists’ efforts do not meet people’s expectations for the following goals: improve public health, solve energy problems and reduce poverty (Supplementary Table 5; see exploratory analyses with reversed hypothesized causality in Supplementary Table 6). In other words, the more people trust scientists, the more they perceive that scientists’ efforts exceed expectations. On the other hand, a higher likelihood that scientists’ perceived efforts exceed people’s expectations is associated with less trust in scientists in the case of developing defence and military technology (that is, those who think scientists are too focused on defence and military technology trust science less).

Discussion

Our 68-country survey challenges the idea that there is a widespread lack of public trust in scientists. In most countries, scientists and scientific methods are trusted. This finding is in line with other international studies on trust in scientists5,6,7. Our study thus confirms, expands and strengthens previous work that refutes the narrative of a wide-ranging crisis of trust. We expand previous studies by providing a comprehensive dataset on trust in scientists post-pandemic and relying on a theoretically informed multidimensional trust measure. We also show that certain factors, such as being male, being conservative, having high SDO and having science-populist attitudes, are correlated with lower trust in scientists.

Public perception of scientific integrity—one of four components of trust—is somewhat high, but perceptions of scientists’ openness are lower. Therefore, scientists wishing to gain public trust could work on being more receptive to feedback and more transparent about their funding and data sources, and invest more effort into communicating about science with the public—which we found to be desired by 83% of respondents. We recommend avoiding top-down communication but encouraging public participation in genuine dialogue, in which scientists seek to consider the insights and needs of other societal actors68.

Trust differs considerably across countries (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 18–21), and there is substantial variation of the trust dimensions, which demonstrates the importance of using multidimensional trust measures like ours in comparative survey research25. This, in turn, will help scientists and science communicators better understand how to act in ways that increase different components of trustworthiness perceptions—that is, competence, integrity, benevolence and openness. Relatedly, trust in scientists varies across population groups, with women, older people and more educated people trusting scientists more. While demographic characteristics probably cannot cause views about scientists per se, they reflect shared direct or mediated experiences with scientists. For example, women’s lived experiences with science are probably different from those of men. Media coverage disproportionally features male scientists and portrays them differently than female scientists, which may evoke different trustworthiness perceptions across genders69,70.

This information can help scientists and science communicators better tailor their communication to different audiences. Our study assessed trust in scientists without distinguishing between different scientific fields. In some countries, trust may depend on the scientists’ discipline and the potential impacts of science on public policy18,71.

Trust and its correlates such as right-leaning and conservative political orientation, education and religiosity clearly vary across countries. This exemplifies the need for more international research that includes underrepresented countries and understudied subpopulations. Our findings also highlight the inconsistency in the association between political orientation depending on the measure used (left–right versus liberal–conservative) and the country of study, as well as the importance of ideology—specifically SDO—in relating to trust in scientists. While previous research finds that SDO is associated with the rejection of specific scientific information, such as the reality of climate change72 or the safety and efficacy of vaccines26, our findings support the idea that SDO may play a more fundamental role in undermining trust in scientists more generally. Scientists who challenge unjust social hierarchies might increase benevolence perceptions among some groups but would probably further decrease trust among people with SDOs. Interventions could be developed to build the perceived trustworthiness of scientists and involve trusted communicators outside of scientific institutions.

While no country has low trust in scientists on average, lack of trust in scientists by even a small minority needs to be taken seriously. Distrusting minorities may affect considerations of scientific evidence in policymaking, as well as decisions by individuals that can affect society at large, especially if they receive extensive news media coverage and include people in positions of power that can influence policymaking11,73,74. A minority of 10% can be sufficient to flip a majority75, and when a critical mass value of 25% is reached, majority opinion can be tipped76. In the context of climate change, an agent-based model showed that an evidence-resistant minority can delay the process of public opinion converging with the scientific consensus77. Future research should investigate the size of these distrusting minorities across countries and their characteristics.

In most countries, a majority of people want scientists to take part in policymaking. Future international comparative research should analyse whether opinions differ depending on a scientist’s expertise regarding a policy issue78 and public support for the policy in question15,79,80. Future studies should also examine whether normative perceptions of science in policymaking shift when specific scientific disciplines or policy issues are mentioned in real-world settings.

A majority of the public wants scientists to prioritize research on public health and solving energy problems. Yet, most people believe that scientists are currently not tackling these issues sufficiently and think that defence and military technology are prioritized too much. As the perceived benefits of science are strongly correlated with trust in scientists, greater consideration of public research priorities by scientists, funding agencies and philanthropists presents an important avenue to increase trust. At the same time, science communication efforts could increasingly focus on highlighting ongoing research on public health and solving energy problems to elevate the prominence of this research in the minds of the public.

Our study has several limitations, mostly related to the international data collection effort. For example, our survey was fielded in English/French in some countries where English/French are not the most commonly spoken languages, including Botswana, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Kenya and Nigeria. This probably resulted in the oversampling of more educated population segments. This limitation arises from the fact that our survey was fielded as an online survey, which considerably limited the representability of populations in certain countries with lower Internet penetration. Furthermore, we showed all participants the same definition of science and scientists at the beginning of the survey to make sure that the participants had a common definition in mind when answering the survey. A similar definition had been pretested and used by the Wellcome Global Monitor, one of the main global studies on trust in science. However, we are aware that introducing a very broad definition of science and scientists excludes other epistemological traditions, such as traditional and indigenous knowledges. While our definition of science reflects the dominant and Western conception of science, we want to acknowledge the importance of traditional and indigenous knowledges. It should further be noted that the words ‘science’ and ‘scientists’ may be interpreted slightly differently across countries. Thus, while we provided a definition of science and scientists at the beginning of the study, we cannot exclude the fact that translations of the words ‘science’ and ‘scientists’ might have slightly different connotations across countries. We provide a more detailed discussion of our limitations in the Supplementary Information.

Newspapers, opinion pieces and books8 have spread narratives of low public trust in scientists. However, such claims remain largely unsubstantiated by empirical evidence5,6,7. Our Many Labs study provides decision makers, scientists and the public with large-scale and open public-opinion data on trust in scientists that can help these stakeholders maintain and potentially increase trust in scientists.

Methods

Overview

The data underlying the analyses were collected in an international pretested, preregistered, cross-sectional online survey (n = 71,922 participants in k = 68 countries) between November 2022 and August 2023 as part of the TISP Many Labs project (‘Trust in Science and Science-Related Populism’). TISP is an international, multidisciplinary consortium of 241 researchers from 179 institutions across all continents. The researchers conducted surveys within 88 post hoc weighted quota samples in 68 countries, using the same questionnaire translated into 37 languages. In the following, we describe the procedures used to collect and analyse the data. Further details are available in the Supplementary Information and Mede et al.46.

Institutional review board approval

Our questionnaire was considered exempt from full institutional review board (IRB) review from the Harvard University Area Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (protocol no. IRB22-1046) in August 2022. A modified IRB application was submitted and considered exempt from full IRB review by the Harvard University Area Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in November 2022 (protocol no. IRB22-1046). All authors have informed themselves whether IRB approval was required from their institutions and obtained IRB approval if necessary. Supplementary Table 22 lists all IRB approvals that were obtained for this study.

Pretest

A pretest with n = 401 participants was conducted in the USA in October 2022. The average completion time was 14 min. After the pretest, the questionnaire was slightly modified, and two questions were added to the survey. The data from the pretest were not included in the final analyses.

Questionnaire

In total, we measured 111 variables. No identifiable information was collected. In the following, we list the measures relevant for this study. The complete questionnaire (in English) is available via the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/7y2br/. The participants were presented with these components in the order in which they are explained below, but the order of questions and items of multi-item scales was randomized.

Consent form

The participants were asked to carefully read a consent form (approved under IRB protocol no. IRB22-1046), which included some general information about the study and the anonymity of the data.

Demographic data—part 1

Participants who consented to participating in the study were then asked to indicate their gender (0 = female, 1 = male, 2 = prefer to self-describe, 99 = prefer not to say), age and level of education (1 = did not attend school, 2 = primary education, 3 = secondary education (for example, high school), 4 = higher education (for example, university degree or higher-education diploma)).

Attention check 1

The first attention check asked the participants to write the number 213 into a comment box. Participants who failed the attention check were redirected to the end of the survey and were not remunerated. See the Supplementary Information for details on how many respondents failed this attention check in the overall sample and across countries.

Definition of science and scientists

The participants were presented with a definition of science and scientists: “When we say ‘science’, we mean the understanding we have about the world from observation and testing. When we say ‘scientists’, we mean people who study nature, medicine, physics, economics, history, and psychology, among other things.” This definition was based on the Wellcome Global Monitor6. We added it because in-depth interviews conducted by the Monitor6 suggested that including a definition would improve the reliability of cross-country comparisons.

Perceived benefits of science

The participants were asked how much they perceived that scientific research benefits people like themselves in their country (1 = not at all, 5 = very strongly) and which geographic region benefits the most and the least from the work that scientists do (1 = Africa, 2 = Asia, 3 = Australia and Oceania, 4 = Europe, 5 = Latin America, 6 = North America).

Desired and perceived goals of science

The participants were asked what goals scientists should prioritize (four items; 1 = very low priority, 5 = very high priority) and how strongly they believed that science aims to tackle these goals (1 = not at all, 5 = very strongly).

Normative perceptions of science and society

The participants rated their agreement with six statements (for example, scientists should be more involved in the policymaking process) (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Five of these statements were taken from ref. 66.

Willingness to be vulnerable to scientists

Participants’ willingness to be vulnerable to scientific guidance was assessed with three items (1 = not at all, 5 = very strongly). Willingness to be vulnerable has been conceptualized as a behavioural trust measure, as it reflects the ceding of authority48.

Trust in scientists

Trust in scientists was assessed with 12 questions on four different dimensions of trustworthiness (that is, competence, integrity, benevolence and openness) (1 = very [unqualified], 5 = very [qualified]), on the basis of Besley et al.48. Psychometric analyses (for example, scale reliability, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, and measurement invariance tests) can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Trust in scientific methods

The participants indicated their level of agreement on whether scientific research methods are the best way to find out if something is true or false (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

General trust in scientists

A single question taken from Funk et al.81 was used to measure the participants’ level of confidence in scientists (1 = no confidence at all, 5 = a great deal of confidence).

Science-related populism

Science-related populist attitudes were assessed with the SciPop Scale38, which comprises eight items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Attention check 2

In the second attention check, the participants were instructed to select ‘strongly disagree’ to a question. Participants who did not select ‘strongly disagree’ were redirected to the end of the survey and were not remunerated. See the Supplementary Information for details on how many respondents failed this attention check in the overall sample and across countries.

SDO

To assess SDO, we used four items from Pratto et al.82 (1 = extremely opposed, 10 = extremely favour).

Demographic data—part 2

The participants indicated their household’s yearly net income (in local currency), their political orientation on a spectrum from liberal to conservative (1 = strongly liberal, 5 = strongly conservative, 99 = I don’t know) and on a spectrum from left-leaning to right-leaning (1 = strongly left-leaning, 5 = strongly right-leaning, 99 = I don’t know), their religiosity (1 = not religious at all, 5 = very strongly religious), and whether they live in a rural or urban area.

Collaborators were allowed to add questions at the end of the survey. Additional questions did not have to be approved by the lead author.

Translations

The original English survey was translated into the local language where necessary. Translations were done by native speakers who were familiar with the study background and, in many cases, had expertise on survey research. Minor linguistic adjustments were made to the survey if deemed necessary. Major changes in the wording of the original survey instrument had to be approved by the project lead. In total, the survey instrument was translated into 36 languages and dialects46.

Preregistration

We submitted a comprehensive preregistration prior to the data collection to the Open Science Framework on 15 November 2022. It included detailed descriptions of our research questions and hypotheses, instruments, data collection, and analytical procedures and is available at https://osf.io/9ksrj. We slightly deviated from the preregistration: we collapsed sparsely populated neighbouring strata for post hoc weighting, excluded confidence in science as a model covariate because of multicollinearity and included SDO as a covariate in the regression model testing predictors of normative perceptions of the role of science in society and politics. Please see the Supplementary Information for deviations from the preregistration.

Power analysis

To determine our minimum target sample size, we ran simulation-based power analyses using the R package simr (v.1.0.7)83, which is designed to conduct power analyses for generalized linear mixed models such as those we used in the main study (for detailed information, see Supplementary Information).

Data collection

Data were collected in surveys that used quotas for age (five bins: 20% 18–29 years, 20% 30–39 years, 20% 40–49 years, 20% 50–59 years and 20% 60 years and older) and gender (two bins: 50% male and 50% female). The participants had to be 18 years of age or older and provide informed consent to participate in the study. The data were collected between November 2022 and August 2023. See Mede et al.46 for an overview of survey periods across countries. The median completion time was 18 min.

The surveys were programmed in Qualtrics. Participants that completed the survey were remunerated according to the market research company’s local rates. All data were collected via online surveys, except in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the participants were interviewed face-to-face and their responses were recorded in Qualtrics by the interviewers. The collaborators were instructed to work with the market research company Bilendi & respondi, except in most African countries, where collaborators collected data with MSi. Convenience samples were not accepted.

A total of n = 72,135 individuals from 88 samples across k = 68 countries completed the survey (n = 71,922 after the exclusion of duplicate respondents). See Mede et al.46 for an overview of all included countries and valid sample sizes across countries (that is, after the exclusion of duplicate respondents) and the Supplementary Information for detailed characteristics of the final sample and the representativeness of the surveyed countries by income and region (Supplementary Tables 12 and 13).

Preparing the dataset

Exclusion of non-completes and data quality test

We excluded all respondents who did not complete the survey, because they cancelled participation during the survey, were filtered as their gender × age quota was already full or did not pass one of the two attention checks. Overall, 4.24% of respondents who reached the first attention check did not pass it (“Please write the number 213 into the comment box”), and 24.38% of respondents who reached the second attention check did not pass it (“To show us that you are still paying attention, please select ‘strongly disagree’”; ref. 46). We excluded all respondents (n = 213) who completed the survey more than once (for example, IP address checks).

Outlier value removal

We removed extreme outlier values for age and household income. Age outliers were defined as values smaller than 18 and bigger than 100. Income outliers were defined as values smaller than zero, equal to zero or outside five times the interquartile range of the log-transformed income distribution within each country after the exclusion of values smaller than or equal to zero. This led to the removal of the age values of 8 respondents and the removal of the income values of 2,457 respondents (1,365 respondents indicated income values equal to or smaller than zero; 1,092 respondents indicated income values outside five times the interquartile range of the log-transformed income distribution within each country after the exclusion of values equal to or smaller than zero).

Post hoc weighting

We computed post-stratification weights with the R package survey (v.4.4-2)84 to ensure that our models would estimate parameters that are representative of the target populations in terms of gender, age and education and have more precise standard errors. We used raking85 to compute four kinds of weights: (1) post-stratification weights at the country level, (2) sample size weights for each country, (3) post-stratification weights for the complete sample and (4) rescaled post-stratification weights for multilevel analyses46.

Scale reliability

Scales were combined into indices, and psychometric properties were assessed for all indices (Supplementary Information), including scale reliability (Cronbach’s α and ω) and cross-country measurement invariances. Scale reliability was good for all scales46.

Analyses

Factors explaining trust in scientists

To investigate explanatory factors of trust in scientists and explore how their influence varies across countries, we ran a blockwise linear multilevel regression analysis with the R package lme4 (v.1.1-35)86. The model included rescaled post-stratification weights87.

All independent variables in the first, second and third blocks were scaled by country means and country standard deviations. All independent variables in the fourth block were scaled by grand means and grand standard deviations.

We first tried to fit a model with random intercepts and random effects for all independent variables. However, this model failed to converge with three negative eigenvalues and also had a singular fit—that is, some random-effects correlations were close to −1/+1, and some random-effects variances were close to 0. This was probably because the random-effects structure was too complex. We therefore simplified the model as follows: to test the effects of the independent variables on trust in scientists, we fitted a model that contained random intercepts across countries (but no random effects) and inspected fixed-effects estimates. To investigate how the influence of the independent variables varies across countries, we fitted separate models, each of which contained random intercepts across countries and random effects for one particular independent variable. This entire procedure was completely in line with our preregistration.

Before we fitted the multilevel models, we confirmed that they would fit the data better than fixed-effects models. First, we inspected intraclass correlations for trust in scientists (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), 0.170). Second, we ran a likelihood-ratio test. It showed that a random-intercept null model explaining trust in scientists had a significantly better fit than a fixed-effects null model (χ2 = 6,024.9, P < 0.001).

Moreover, we tested for multicollinearity of independent variables for the most complex model—that is, after the inclusion of all three blocks of independent variables (Supplementary Table 16). All variance inflation factors were well below even a very conservative threshold value of 4 (ref. 88).

Normative perceptions of science in policymaking

To examine whether the public demands that scientists should take an active role in society and policymaking, we ran two analyses. First, we computed weighted probabilities of responses to the five items measuring these perceptions. This analysis provided estimates that are approximately representative with regard to gender, age, education and country sample size. Second, we tested explanatory factors of normative perceptions of science in policymaking and society: we fitted a linear multilevel regression model with the R package lme4 (ref. 86), which explained the average agreement with the five individual items measuring those perceptions, included the rescaled post-stratification weights, and contained trust in scientists, science-related populist attitudes and sociodemographic variables as independent variables—that is, gender (binary; 1 = male), age (continuous), education (binary; 1 = tertiary education), annual household income in US dollars (continuous, log-transformed), place of residence (binary; 1 = urban), right-leaning political orientation (continuous), conservative political orientation (continuous) and religiosity. All independent variables were scaled by country means and country standard deviations.

We specified random intercepts across countries and random effects for trust in scientists and science-related populist attitudes. Significance tests of regression estimates relied on the Satterthwaite method89. Before we fitted the multilevel model, we confirmed that it would fit the data better than a fixed-effects model. First, we inspected the intraclass correlation of the normative perceptions index (ICC = 0.104). Second, we ran a likelihood-ratio test, which showed that a random-intercept null model had a significantly better fit than a fixed-effects null model (χ2 = 3,780.6, P < 0.001). Moreover, we tested for multicollinearity of independent variables (Supplementary Table 17). All variance inflation factors were well below even a very conservative threshold value of 4 (ref. 88).

Perceived and desired priorities of scientific research

To explore desires that scientists should prioritize four specific goals (improving public health, solving energy problems, reducing poverty, and developing defences and military technology) as well as perceptions that science actually tackles these goals, we ran three analyses. First, we inspected weighted mean values of responses to the four items measuring priority desires as well as weighted mean values of responses to the four items measuring perceptions that science actually devotes efforts to the four goals.

Second, we ran weighted paired-samples t-tests to analyse whether mean values of desires and perceptions differed significantly from each other. These analyses provided estimates that are approximately representative with regard to gender, age, education and country sample size.

Third, we tested explanatory factors of the discrepancy between the desire that scientists should prioritize the four goals and perceptions that science actually tackles them. To do so, we ran four blockwise linear multilevel regression analyses with the R package lme4 (ref. 86). Each model explained the discrepancy between desires that scientists should prioritize one of the four goals and perceptions that science actually tackles them, with higher outcome variable values indicating that perceptions are more likely to exceed desires and lower outcome variable values indicating that perceptions are more likely to stay behind desires. All models included rescaled post-stratification weights87.

For each of the four models, we specified random intercepts across countries and random effects for trust in scientists and science-related populist attitudes. Significance tests of regression estimates relied on the Satterthwaite method89. Before we fitted the multilevel models, we confirmed that they would fit the data better than fixed-effects models. First, we inspected the intraclass correlations of the four discrepancy scores (health: ICC = 0.112; energy: ICC = 0.079; poverty: ICC = 0.134; defence: ICC = 0.107). Second, we ran likelihood-ratio tests, which showed that random-intercept null models had significantly better fit than fixed-effects null models (health: χ2 = 3,246.2, P < 0.001; energy: χ2 = 2,264.4, P < 0.001; poverty: χ2 = 4,835.2, P < 0.001; defence: χ2 = 3,669.0, P < 0.001). Moreover, we tested for multicollinearity of independent variables for the most complex models (Supplementary Table 18). All variance inflation factors were well below even a very conservative threshold value of 4 (ref. 88).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The dataset underlying this Article is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5C3QD. Mede et al.46 provide detailed information on the dataset, including data collection and preprocessing.

Code availability

The code for replicating the analyses underlying this Article is publicly available at https://osf.io/wj34h/.

References

-

Algan, Y., Cohen, D., Davoine, E., Foucault, M. & Stantcheva, S. Trust in scientists in times of pandemic: panel evidence from 12 countries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2108576118 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Sturgis, P., Brunton-Smith, I. & Jackson, J. Trust in science, social consensus and vaccine confidence. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1528–1534 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Cologna, V. & Siegrist, M. The role of trust for climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviour: a meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 69, 101428 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Cologna, V., Hoogendoorn, G. & Brick, C. To strike or not to strike? An investigation of the determinants of strike participation at the Fridays for Future climate strikes in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 16, e0257296 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

IPSOS Global Trustworthiness Monitor: Stability in an Unstable World (IPSOS, 2022).

-

Wellcome Global Monitor: How Does the World Feel about Science and Health? (Wellcome, 2018); https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/wellcome-global-monitor-2018.pdf

-

Wellcome Global Monitor: How COVID-19 Affected People’s Lives and Their Views about Science (Wellcome, 2020); https://cms.wellcome.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/Wellcome-Global-Monitor-Covid.pdf

-

Nichols, T. M. The Death of Expertise: The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

-

Jamieson, K. H. Crisis or self-correction: rethinking media narratives about the well-being of science. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2620–2627 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Shanahan, E. A., Mcbeth, M. K. & Hathaway, P. L. Narrative policy framework: the influence of media policy narratives on public opinion. Polit. Policy 39, 373–400 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Toff, B. Exploring the effects of polls on public opinion: how and when media reports of policy preferences can become self-fulfilling prophesies. Res. Polit. 5, 2053168018812215 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Sonck, N. & Loosveldt, G. Impact of poll results on personal opinions and perceptions of collective opinion. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 22, 230–255 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Hendriks, F., Kienhues, D. & Bromme, R. Measuring laypeople’s trust in experts in a digital age: the Muenster Epistemic Trustworthiness Inventory (METI). PLoS ONE 10, e0139309 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Wintterlin, F. et al. Predicting public trust in science: the role of basic orientations toward science, perceived trustworthiness of scientists, and experiences with science. Front. Commun. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.822757 (2022).

-

Cologna, V., Baumberger, C., Knutti, R., Oreskes, N. & Berthold, A. The communication of value judgements and its effects on climate scientists’ perceived trustworthiness. Environ. Commun. 16, 1094–1107 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bromme, R., Mede, N. G., Thomm, E., Kremer, B. & Ziegler, R. An anchor in troubled times: trust in science before and within the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 17, e0262823 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Motta, M. The enduring effect of scientific interest on trust in climate scientists in the United States. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 485–488 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

McCright, A. M., Dentzman, K., Charters, M. & Dietz, T. The influence of political ideology on trust in science. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 044029 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Azevedo, F. & Jost, J. T. The ideological basis of antiscientific attitudes: effects of authoritarianism, conservatism, religiosity, social dominance, and system justification. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 518–549 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Mede, N. G. Legacy media as inhibitors and drivers of public reservations against science: global survey evidence on the link between media use and anti-science attitudes. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 9, 40 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Rutjens, B. T. et al. Science skepticism across 24 countries. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 13, 102–117 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Chan, E. Are the religious suspicious of science? Investigating religiosity, religious context, and orientations towards science. Public Underst. Sci. 27, 967–984 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Ardèvol-Abreu, A., Diehl, T., Gómez Patiño, M. & Liu, J. H. Trust in institutional actors across 22 countries. Examining political, science, and media trust around the world. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 74, 237–262 (2019).

-

Siegrist, M., Cvetkovich, G. & Roth, C. Salient value similarity, social trust, and risk/benefit perception. Risk Anal. 20, 353–362 (2000).

Google Scholar

-

Besley, J. C. & Tiffany, L. A. What are you assessing when you measure ‘trust’ in scientists with a direct measure? Public Underst. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625231161302 (2023).

-

Ghai, S., Forscher, P. S. & Chuan-Peng, H. Big-team science does not guarantee generalizability. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1053–1056 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Forscher, P. S. et al. The benefits, barriers, and risks of big-team science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 18, 607–623 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Odeny, B. & Bosurgi, R. Time to end parachute science. PLoS Med. 19, e1004099 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Dubow, S. Racial irredentism, ethnogenesis, and white supremacy in high-apartheid South Africa. Kronos 41, 236–264 (2015).

-

Brandt, A. M. Racism and research: the case of the Tuskegee syphilis study. Hastings Cent. Rep. 8, 21–29 (1978).

Google Scholar

-

Scharff, D. P. et al. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 21, 879–897 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

West, J. D. & Bergstrom, C. T. Misinformation in and about science. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e1912444117 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Roozenbeek, J. et al. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 201199 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Hendriks, F., Kienhues, D. & Bromme, R. Replication crisis = trust crisis? The effect of successful vs failed replications on laypeople’s trust in researchers and research. Public Underst. Sci. 29, 270–288 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Rutjens, B. T. & Većkalov, B. Conspiracy beliefs and science rejection. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 46, 101392 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Douglas, K. M. Are conspiracy theories harmless? Span. J. Psychol. 24, e13 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Mede, N. G. & Schäfer, M. S. Science-related populism: conceptualizing populist demands toward science. Public Underst. Sci. 29, 473–491 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Mede, N. G., Schäfer, M. S. & Füchslin, T. The SciPop scale for measuring science-related populist attitudes in surveys: development, test, and validation. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 33, 273–293 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Funk, C., Tyson, A., Kennedy, B. & Johnson, C. Science and Scientists Held in High Esteem across Global Publics (Pew Research Center Science & Society, 2020); https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/29/science-and-scientists-held-in-high-esteem-across-global-publics/

-

Li, N. & Qian, Y. Polarization of public trust in scientists between 1978 and 2018: insights from a cross-decade comparison using interpretable machine learning. Polit. Life Sci. 41, 45–54 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Sidanius, J. & Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1999); https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139175043

-

Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., Martin, M. & Stallworth, L. M. Consensual racism and career track: some implications of social dominance theory. Polit. Psychol. 12, 691–721 (1991).

Google Scholar

-

Kerr, J. R. & Wilson, M. S. Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation predict rejection of science and scientists. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 550–567 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Achterberg, P., de Koster, W. & van der Waal, J. A science confidence gap: education, trust in scientific methods, and trust in scientific institutions in the United States, 2014. Public Underst. Sci. 26, 704–720 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Besley, J. C., Lee, N. M. & Pressgrove, G. Reassessing the variables used to measure public perceptions of scientists. Sci. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547020949547 (2020).

-

Mede, N. G. et al. Perceptions of science, science communication, and climate change attitudes in 68 countries: the TISP dataset. Sci. Data. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04100-7 (2025).

-

Putnick, D. L. & Bornstein, M. H. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: the state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev. Rev. 41, 71–90 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Besley, J. C., Lee, N. M. & Pressgrove, G. Reassessing the variables used to measure public perceptions of scientists. Sci. Commun. 43, 3–32 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Rutjens, B. T. & van der Lee, R. Spiritual skepticism? Heterogeneous science skepticism in the Netherlands. Public Underst. Sci. 29, 335–352 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

McPhetres, J., Jong, J. & Zuckerman, M. Religious Americans have less positive attitudes toward science, but this does not extend to other cultures. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 12, 528–536 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

De Cruz, H. in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (eds Zalta, E. N. & Nodelman, U.) https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/religion-science/ (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford Univ., 2022).

-

Johnson, C., Thigpen, C. & Funk, C. On the Intersection of Science and Religion (Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project, 2020); https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2020/08/26/on-the-intersection-of-science-and-religion/

-

Vlasceanu, M. et al. Addressing climate change with behavioral science: a global intervention tournament in 63 countries. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj5778 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Van Bavel, J. J. et al. National identity predicts public health support during a global pandemic. Nat. Commun. 13, 517 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

De keersmaecker, J., Schmid, K., Sibley, C. G. & Osborne, D. The association between political orientation and political knowledge in 45 nations. Sci. Rep. 14, 2590 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Lasco, G. & Curato, N. Medical populism. Soc. Sci. Med. 221, 1–8 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Otjes, S. & Rekker, R. Socialised to think in terms of left and right? The acceptability of the left and the right among European voters. Elect. Stud. 72, 102365 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Weeden, J. & Kurzban, R. Do people naturally cluster into liberals and conservatives? Evol. Psychol. Sci. 2, 47–57 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Thorisdottir, H., Jost, J. T., Liviatan, I. & Shrout, P. E. Psychological needs and values underlying left–right political orientation: cross-national evidence from eastern and western Europe. Public Opin. Q. 71, 175–203 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Bauer, P. C., Barberá, P., Ackermann, K. & Venetz, A. Is the left–right scale a valid measure of ideology? Polit. Behav. 39, 553–583 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

2022 Corruption Perceptions Index (Transparency International, 2022); https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022

-

Bauer, M. W. The Cultural Authority of Science: Comparing across Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas (Routledge, 2018).

-

Clausen, B., Kraay, A. & Nyiri, Z. Corruption and confidence in public institutions: evidence from a global survey. World Bank Econ. Rev. 25, 212–249 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Jong-sung, Y. & Khagram, S. A comparative study of inequality and corruption. Am. Sociol. Rev. 70, 136–157 (2005).

Google Scholar

-

Sturgis, P. & Allum, N. Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Underst. Sci. 13, 55–74 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Cologna, V., Knutti, R., Oreskes, N. & Siegrist, M. Majority of German citizens, US citizens and climate scientists support policy advocacy by climate researchers and expect greater political engagement. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 024011 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Besley, J. C. The National Science Foundation’s science and technology survey and support for science funding, 2006–2014. Public Underst. Sci. 27, 94–109 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Bubela, T. et al. Science communication reconsidered. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 514–518 (2009).

Google Scholar

-

Freedman, G., Moutoux, I., Hermans, I. & Green, M. C. ‘She made a mean beef stroganoff’: gendered portrayals of women in STEM in newspaper articles and their effects. Commun. Monogr. 91, 262–282 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Mitchell, M. & McKinnon, M. ‘Human’ or ‘objective’ faces of science? Gender stereotypes and the representation of scientists in the media. Public Underst. Sci. 28, 177–190 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Myers, T. A. et al. Predictors of trust in the general science and climate science research of US federal agencies. Public Underst. Sci. 26, 843–860 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Stanley, S. K. & Wilson, M. S. Meta-analysing the association between social dominance orientation, authoritarianism, and attitudes on the environment and climate change. J. Environ. Psychol. 61, 46–56 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Franta, B. Weaponizing economics: Big Oil, economic consultants, and climate policy delay. Environ. Polit. 31, 555–575 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Oreskes, N. & Conway, E. M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (Bloomsbury, 2010).

-

Xie, J. et al. Social consensus through the influence of committed minorities. Phys. Rev. E 84, 011130 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Centola, D., Becker, J., Brackbill, D. & Baronchelli, A. Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention. Science 360, 1116–1119 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Lewandowsky, S., Pilditch, T. D., Madsen, J. K., Oreskes, N. & Risbey, J. S. Influence and seepage: an evidence-resistant minority can affect public opinion and scientific belief formation. Cognition 188, 124–139 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Oreskes, N. What is the social responsibility of climate scientists? Daedalus 149, 33–45 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Beall, L., Myers, T. A., Kotcher, J., Vraga, E. K. & Maibach, E. W. Controversy matters: impacts of topic and solution controversy on the perceived credibility of a scientist who advocates. PLoS ONE 12, e0187511 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Kotcher, J., Myers, T. A., Vraga, E. K., Stenhouse, N. & Maibach, E. W. Does engagement in advocacy hurt the credibility of scientists? Results from a randomized national survey experiment. Environ. Commun. 11, 415–429 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Funk, C., Hefferon, M., Kennedy, B. & Johnson, C. Trust and Mistrust in Americans’ Views of Scientific Experts (Pew Research Center Science & Society, 2019); https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/08/02/trust-and-mistrust-in-americans-views-of-scientific-experts/

-

Pratto, F. et al. Social dominance in context and in individuals: contextual moderation of robust effects of social dominance orientation in 15 languages and 20 countries. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 4, 587–599 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Green, P. & MacLeod, C. J. SIMR: an R package for power analysis of generalized linear mixed models by simulation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 493–498 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Lumley, T. survey: Analysis of complex survey samples. R package v.4.4-2 https://cran.r-project.org/package=survey (2023).

-

Battaglia, M. P., Hoaglin, D. C. & Frankel, M. R. Practical considerations in raking survey data. Surv. Pract. https://doi.org/10.29115/SP-2009-0019 (2009).

-

Bates, D. et al. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using ‘Eigen’ and S4. R package v.1.1-35 https://cran.r-project.org/package=lme4 (2023).

-

Patil, I. et al. datawizard: Easy data wrangling and statistical transformations. R package v.0.12.03 https://cran.r-project.org/package=datawizard (2023).

-

O’brien, R. M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 41, 673–690 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Satterthwaite, F. E. Synthesis of variance. Psychometrika 6, 309–316 (1941).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements