The concept of visual communication is essentially as old as humanity itself. The evidence extends far back into prehistoric times, with the primitive drawings, notched bones, marked stones, and representational paintings that would eventually be discovered in archeological digs and on cave walls not only predating all forms of written language, but also forming the basis for them. Millenia later, only the implements have changed, as kids make crude crayon or marker pictures well before they learn how to write letters and words. The therapeutic connection between perception, process, and two-dimensional manifestation is the basis for artist and educator Andrea Kantrowitz’s book Drawing Thought: How Drawing Helps Us Observe, Discover, and Invent (MIT Press, 2022).

“I was drawing before I could walk,” says the author, who grew up in the Boston suburbs and currently serves as the director of SUNY New Paltz’s Art Education program. “My older sister also drew, so she encouraged me to draw as well.” Kantrowitz’s parents nurtured her creativity as well: Her mother, a librarian, sparked her love of books, while her father, an inventor and literal rocket scientist who developed the ceramic coating that helps spacecraft withstand reentry and worked in medical innovation, further ignited her intellectual and creative aspirations. “Ideas just came to him,” she recalls. “He really made me understand how human beings are capable of almost anything when they use their imaginations.” It’s this precept, and how drawing can help exponentially to unlock it, that informs the 200-page Drawing Thought, whose points and exercises are beautifully illustrated with Kantrowitz’s own work. “At its root, drawing is play,” she explains. “But it’s also a way to figure things out, to imagine what is possible.”

Cognition Connection

“In fifth grade, I devoured every single ‘How to Draw’ book in our school library,” Kantrowitz writes. “Then, at about 16, I discovered life drawing and I was hooked. It wasn’t easy to draw live models but I found I could get better by studying other people’s drawings.” When she was 17 she studied with influential Art Students League of New York artistic anatomy instructor Robert Beverly Hale, who had a profound effect on the honing of her technique. “He taught me to look for the ‘bony landmarks’ in the live models and drawings by the old masters,” she says. Another revelatory encounter was the discovery of the 17th-century Chinese instructional book Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, a timeless text with beautiful illustrations that covers nature and landscape drawing as well as figure drawing. “Skilled drawers often learn ‘how to see,’” she notes in Drawing Thought, “because they have learned what to look for.”

When she attended Harvard, it was this connection between perception and artistic execution that became the foundation for her creation of the curriculum that earned her a BA in a bespoke program she called Arts and Cognition. “I had a friend who was a musician, and he majored in Music and Philosophy, so that sort of gave me the idea to put two things together: cognitive psychology and art,” Kantrowitz says. “My dad always told me to ‘think big,’ so that was part of it, too.” An MFA in Painting at Yale followed, and by the late 1980s she was in San Francisco, where she began to think even bigger, taking part in community organizing efforts and looking for ways to make her art background meaningful on a wider scale. “I had been in an ivory tower for the last few years before that,” she says. “And I decided that I didn’t want to just be someone who designed pretty wallpaper for rich people.”

Striking Presence

One of the major events that took place during her time in the Bay Area was the Watsonville Cannery strike. From September 1985 to March 1987, workers at the frozen food processing facility, many of them Mexican immigrants and all of them union members, went on strike when the plant’s parent company, Watsonville Canning, moved to reduce their wages and benefits. Kantrowitz was compelled to get involved, making murals and posters to bring attention to the strike and spending weeks with workers on the picket line and at the union hall to chronicle their plight through interviews and drawings (much of her art from the Watsonville strike is now archived in public and private collections). “I would talk to the people while I was drawing them and let them tell their stories,” she says. “But mostly I would just sit quietly, looking and listening while I drew. It was a powerful experience.”

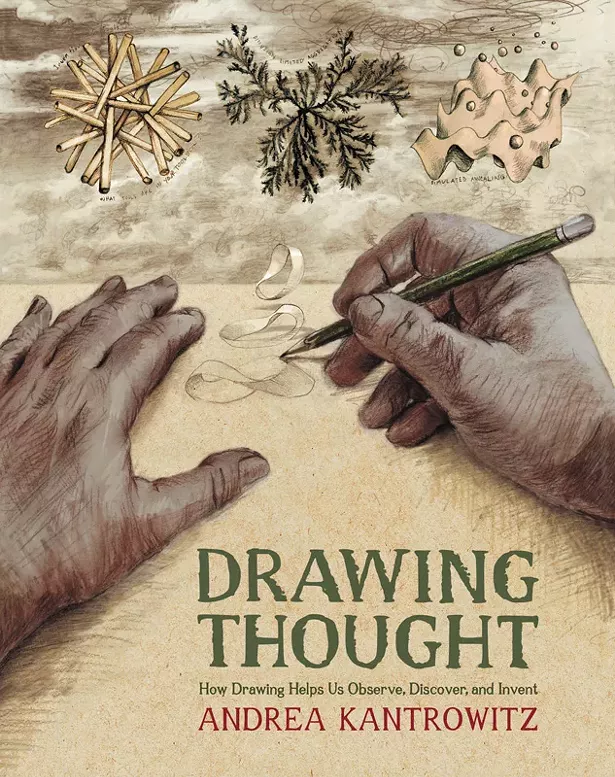

<a href="https://media1.chronogram.com/chronogram/imager/u/original/22700176/dtcover.webp" rel="contentImg_gal-22684269" title="In 2022, SUNY New Paltz professor Andrea Kantrowitz published Drawing Thought, which contains art exercises designed to unlock creativity. “At its root, drawing is play,” Kantrowitz says. “But it’s also a way to figure things out, to imagine what is possible.” The image below is a spread from the book. The author is pictured left." data-caption="In 2022, SUNY New Paltz professor Andrea Kantrowitz published Drawing Thought, which contains art exercises designed to unlock creativity. “At its root, drawing is play,” Kantrowitz says. “But it’s also a way to figure things out, to imagine what is possible.” The image below is a spread from the book. The author is pictured left.

” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

In 2022, SUNY New Paltz professor Andrea Kantrowitz published Drawing Thought, which contains art exercises designed to unlock creativity. “At its root, drawing is play,” Kantrowitz says. “But it’s also a way to figure things out, to imagine what is possible.” The image below is a spread from the book. The author is pictured left.

Her first teaching job was as foundations coordinator at the University of Wisconsin in Oshkosh; a position at the College of New Rochelle would come later. But, as it has for so many in the arts, the road led back east to New York, where she enrolled in the doctoral program at Columbia University Teachers College. At Columbia she befriended Nick Soumanis, a cartoonist and fellow doctoral student and future teacher who would rework his dissertation on using comics as a teaching tool into the award-winning 2015 graphic novel Unflattening. “Besides just being a great pure artist, Andrea is really good at the art of looking—of doing giant closeups of really small things and showing how they work,” says Soumanis, who has collaborated with Kantrowitz and others on performances that combine drawing and comics with live dance. “She knows how to connect science with art and thinking. Drawing has become culturally undervalued, especially now, with AI. Drawing is actually a really important mode of thinking, one that you’ve got to use, whether you’re an artist or even a non-artist. And Andrea’s book and her teaching shows how you can do that.”

Drawn to Teaching

As a teaching artist in the New York City public school systems for several years, Kantrowitz worked on local and national art-education research projects. From 2005 to 2014 she worked with the Studio in a School organization, where she codeveloped and implemented a curriculum that integrated art, math, and literacy as part of a federally funded Arts in Education Model Development and Dissemination project. A key component of the project was a randomized control trial demonstrating the impact of an integrated art curriculum for underprivileged students. “I did my fellowship in East Harlem, and the program there was really successful in getting kids to want to explore [academically] on their own and to use their imaginations at a higher level,” says the instructor. “The afterschool comics group was really popular, because so many of the kids loved anime. We took a field trip to Japan Society Museum to see an anime exhibit and the kids knew more about what was on view than the guides at the museum did.”

<a href="https://media1.chronogram.com/chronogram/imager/u/original/22700170/guide_–_andrea_whydraw_138_9.webp" rel="contentImg_gal-22684269" title="A page out of Drawing Thought." data-caption="A page out of Drawing Thought.

” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

A page out of Drawing Thought.

Kantrowitz taught at Pratt Institute and the Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University before starting at SUNY New Paltz in 2016 and has been vital in shaping the school’s art curriculum since her arrival. In many ways, Drawing Thought is the realization of her long, ongoing, and highly impactful career in arts education and, pun intended, the perfect illustration of her practice as both an artist and a teacher that skillfully combines her beautiful hand-drawn images with insightful, autobiographical text discussing the discipline and its related aspects of neuroscience and cognitive psychology. “Drawing lets us dive below the surface of our conscious thoughts,” writes Kantrowitz, “to observe and record sensations, perceptions, and ideas that might otherwise slip by unnoticed.” Since its publication, the tome has elicited wide praise in the academic sphere and has been added as a boilerplate textbook at numerous educational institutions.

“What made me want to do this book was, basically, thinking about why art is valuable to society,” says Kantrowitz, a mother of two who curates exhibitions and continues to display her art publicly; a recent showing was at SUNY New Paltz’s Dorsky Museum. “Drawing talks back to us. It gives us a feeling of aliveness and beauty, of keeping open the possibilities and being awake and in the moment, despite whatever shit is happening in the world. I still draw every day. I’ve never stopped.”